Not Dead & Not For Sale (9 page)

Read Not Dead & Not For Sale Online

Authors: Scott Weiland

I

N LOVE WITH MARY FROM A DISTANCE,

living with Jannina up close. Guilt was my best friend, my worst enemy, my motivator, and my tormentor.

Free from time, suspended in space.

Purple

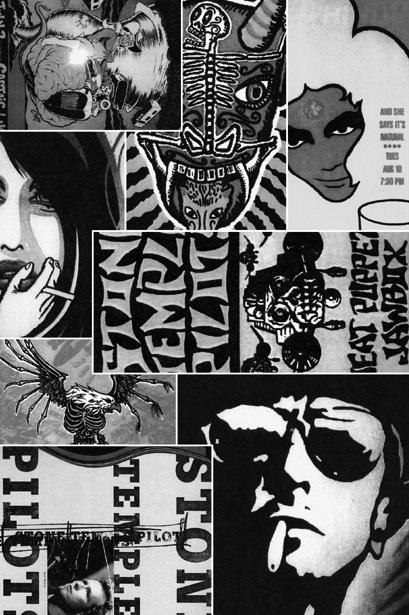

was recorded outside of time and space, inside Atlanta, where I found a drug dealer down in funky town. She was twenty-five and, unfortunately, HIV positive. Her boyfriend was a death rocker with a death wish. Kurt Cobain was still alive. Grunge, as they labeled it, was still king—of music, social awareness, and even high fashion.

I was living to score because my habit had me sick and the downers and barbiturates weren’t getting me well. The girl with AIDS was my key to heroin health. I got my bags of good shit and my clean rigs; I was cool to record. We cut and mixed the whole album in less than a month. Then it was back to L.A., where my fucking habit, begun on the Barbecue Mitzvah Tour, had grown up into a big black monster.

Jannina and I had moved into a house in remote and rustic Topanga Canyon, a world away from the nasty streets that sold the stuff I craved. I had to stop. I planned to wean off. By the second day, though, I failed and was flying high. I knew I needed bodily health, knew I needed to detox. I found a rehab place in Marina del Rey called Exodus. Just as I was about to check in, I was told not to. Kurt Cobain and Gibby Haynes were there.

Gibby was my Butthole Surfer buddy from the Barbecue Mitzvah Tour, where we had gone off the rails. My business manager didn’t think it was a good idea for us to be together, so I went to a treatment center in Pasadena where, two days later, I learned that Kurt had left Exodus. Four days after that I was told that Kurt was dead. The news frightened and devastated me, driving me into more dark solitude. The news had me searching all the silent places in my brain for explanations and comfort. This was April of 1994.

Confusing matters more was the sensational success of

Purple

. After trashing

Core

, the critics finally came our way and embraced

Purple

, validating STP as a legitimate rock band with an artistic attitude all our own. The public also dug it. When the record dropped in June of that same year, it debuted at number one. “Interstate Love Song” was a huge hit. So were “Vasoline” and “Big Empty,” which said, “Too much walkin’, shoes worn thin … too much trippin’, and my soul’s worn thin.”

We went on tour. Europe was cool, but Germany was freezing cold. We were set to fly back to the States and do MTV’s

Spring Break

in Florida. Hungry for sunshine, we planned on arriving a few days before the show. But our manager pushed back our departure date due to our obligation to do major press in Germany. But we eventually made it to Florida.

The big thrill there was a woman I’ll call Alison. She was an edgy photographer. Dean and I were both drawn to her. She was blond, sexy, a little older, and a hard-core junkie. No, there was no three-way. I did, however, form a bond with Alison that lasted quite awhile.

Alison was an intriguingly talented hot mess. She could hang with the boys and talk trash. She was big fun for the funksters, with no strings attached. Alison had a longer relationship with dope than I did. We barely crossed narcotic paths; our get-high times together were few. She was a far more advanced student of the scene. I learned from her in many ways. She lived at the fertile crossroads of art and dope. Miraculously, though, Alison got clean while I stayed stuck in the mud and murk for years to come.

Now it was 1995, the year that should have been the best year of my life. It was the worst. I was busted for possession. I faced a trial for drug possession, where I got three years suspended sentence and five months in drug jail. And STP fell apart.

Headlining at Madison Square Garden—Aerosmith joined us onstage

I

LIKE

PURPLE

MORE THAN

CORE

. For all it strengths,

Core

was a little bit of a production compromise. Because we knew what we were doing in terms of song stylings and studio sounds,

Purple

was more honest and more autobiographical. It was also more heartfelt and heartsick.

“Vasoline,” for example, is about being stuck in the same situation over and over again. It’s about me becoming a junkie. It’s about lying to Jannina and lying to the band about my heroin addiction. “You search for things,” I wrote, “that you can’t see. Going blind, out of reach, somewhere in the Vasoline.”

“Unglued” hits the same theme. I’m hooked. “I got this thing,” I sing, “it’s coming over me. Moderation is masturbation … this confusion is my illusion … all these things I’m sick about … I kick about … always come unglued.”

“Pretty Penny” is still another drug story, a mother-daughter junkie team who are “blown away and lost the pearl and price [they] paid.”

“Interstate Love Song” was written about the phone calls I had with Jannina. She’d ask how I was doing, and I’d lie, say I was doing fine. Chances are I had just fixed before calling her. I imagined what was going through her mind when I wrote, “Waiting on a Sunday afternoon for what I read between the lines, your lies, feelin’ like a hand in rusted shame, so do you laugh or does it cry? Reply?”

And yet I sincerely missed her, sincerely felt for her. Those romantic feelings were expressed in a song for Jannina I called “Still Remains”: “Pick a song and sing a yellow nectarine … take a bath, I’ll drink the water that you leave … if you should die before me, ask if you can bring a friend, pick a flower, hold your breath, and drift away.”

The record also reflected my feelings about the mish-mash state of the music business. Everyone seemed to be living or dying but making real money.

When the record was finished, a music writer asked me, “Why did you call it

Purple

?”

“Because it sounds purple,” I said. “Besides, that’s a stupid question. Why is your rag called

Spin

?”

AFTER

PURPLE

WAS FINALLY FINISHED,

I came home to Topanga Canyon emotionally distraught and incredibly needy. I needed something steady; I needed to be cared for. I took Jannina down to the beach and asked her to marry me.

She said yes and suggested that the wedding take place in her aunt and uncle’s beautiful home in San Marino, the exclusive old-money section of Pasadena where the streets are lined with mansions. The wedding was extravagant—family, friends, music moguls. I snuck off with the groomsmen to do coke in the limo. My friend Eddie Nichols, the singer for Royal Crown Revue, sang “Stormy Weather,” a good indication of what lay ahead.

Jannina and I went to the Greek isles for our honeymoon and stayed in an ancient white alcove in the side of a mountain. After a few days of drinking homemade ouzo, we flew off to Cancún and swam in the warm water. I was still in the process of kicking heroin and had enough morphine sulfate pills and Vicodin to get me through.

Back home, Jannina got really sick and wound up in the hospital, where they gave her a shot of morphine. At the time I was two months clean, but viewing her injection set off sirens in my head, especially when I saw such peace and calm come over her face. I left the hospital to look for my dealer. An hour later, I was loaded.

Nonetheless, we pursued the dream of domestic happiness. From her aunt and uncle, we bought the home in which we were married—Jannina’s dream home—and began to live a life of luxury, collecting antiques and cars.

A YEAR LATER, I GOT HOME FROM TOURING

behind

Purple

and was promptly arrested close to my home in Pasadena for trying to score. I was getting sloppy.

Jannina bailed me out. “I’m dope sick,” I told her. “You gotta get me well. You gotta get me to my dealer. Then we’ll make a plan for me to kick, but first I’ve gotta get well.”

“No,” said Jannina. “Fuck that. I will not take you to your dealer. I hate that bitch!”

I got into our ’65 Mustang convertible with Jannina behind the wheel. I begged her to change her mind.

“It’s my medicine,” I said to her. “I need my medicine.”

Jannina wouldn’t budge. I was desperate. As the car made a right turn going 10 or 15 miles an hour, I jumped out, hit the ground, and started rolling. Jannina didn’t look back. Jannina had had enough. I was so sick I’d do anything to score—fuckin’ anything. I found a payphone and called my one hope, the lady who’d been supplying me. In my mind, I knew I had a fifty-fifty chance of finding her at home.

She picked up the phone! Fuck, I was relieved!

“You gotta come here and get me,” I pleaded. “You gotta pick me up.”

“No way. If you want it, come get it.”

I came in a cab. The fare, plus the cost of the dope, exhausted my funds. All I had left was an ATM card. Loaded, I made it over to the Chateau Marmont, the old-school Hollywood hotel where artists came to live or die. That’s where I ran into another one of my dealer’s best customers, Courtney Love. She was with Amanda de Cadenet, the photographer/socialite. As fate would have it, their room was next to mine. That night Courtney and I got high as she and Amanda dressed for dinner at the home of Jack Nicholson. For a while, Ms. Love inserted herself into my ever-more-erratic story. We were never lovers but were rather close at the start. She was this intriguing character who required constant attention. When, for example, she nodded out on dope, she never failed to do so sitting in a chair and spreading her legs wide. I kept hearing the Stones singing, “Oh yeah, she’s a starfucker, starfucker, starfucker, starfucker!”

When word of my arrest in Pasadena became public, I was still living at the Marmont and partying hard. The press was asking me for a statement concerning my drug bust. I didn’t want to go on TV, so I wrote something and gave it to Courtney to read on my behalf. She was delighted to be my spokesperson. In essence, I said that I would never advocate drugs for anyone, that I was not in great shape but hoping to get better.

It was not a particularly strong statement, but at that point I was not a particularly strong man. I was groping, grieving, and getting more fucked up on heroin, a drug that simultaneously made me feel bad, feel good, and feel bad for feeling good. Confusion reigned. The din inside my brain was louder than the din of a dozen metal bands. Only heroin could turn up the quiet. Only heroin took me to the place where shame, guilt, and remorse were magically washed away.