Not Dead & Not For Sale (4 page)

Read Not Dead & Not For Sale Online

Authors: Scott Weiland

N

O ONE TURNS YOU INTO A DRUG ADDICT OR DRUNK

. The blame game is pointless and harmful. I don’t believe in pointing fingers. We do what we do and are responsible for our own actions. I don’t believe we are victimized by circumstance. There are, however, stories to be told. The story does not begin with us, but rather our parents, and our parents’ parents. The story goes back further than we know or can even imagine. Our stories are linked together because we share this space on the planet. We influence one another, whether we like it or not.

I love my mother. Without doubt she’s been my biggest supporter—true, loving, and loyal. She’s an independent woman who has always held down well-paying professional jobs. She’s smart, understanding, and kind. She’s also identified herself as an alcoholic.

When I was a preteen and still living in Cleveland, my stepfather took our family to a Cavaliers basketball game. We sat in the private box owned by TRW, his employer, that had leather seats and a fully stocked bar. After the game was over, Dave went into my mother’s purse to look for something. He discovered a bottle of vodka that Mom was stealing from the bar. That’s how she was busted.

She had hit bottom—or enough of a bottom for her to feel remorse and respond honestly. She admitted her problem. In front of Dave, me, and Michael, she started crying. She said she was a loser. We cried even louder and said, “Mom, you’re not a loser. We love you.”

At the time, I didn’t know the meaning of alcoholism. All I knew was that Mom was calling herself a horrible mother, and I knew that wasn’t true. I knew she cared for us deeply. I watched her join a twelve-step program that she followed diligently. She didn’t drink for some twenty-five years, and only started again after she learned that both her sons were heroin users. She slipped, as I have slipped, as I come from a long line of slippers. My uncle—Mom’s brother—was an alcoholic and coke addict. My grandparents—Mom’s mother and father—were hard-core alcoholics. Booze runs wild in my family.

JERRY JEFF WALKER SANG A SONG

called “Jaded Lover.” I heard it for the first time during one of those summers that I spent with my biological father, Kent. Dad could sing like Jerry Jeff; he could also sound like George Strait. His voice was resonant and deep and full of warmth. In a strange way, when I listened to the lyrics of “Jaded Lover”—“Well, it won’t be but a week or two … you’ll be out lovin’ someone new”—I thought of the troubled relationship between me and Dad.

I felt like the jaded lover, the son he gave up, the son he could never quite embrace, the son who wanted the father more than the father wanted the son.

MY EARLIEST SEXUAL EXPERIENCES WERE NOT JOYFUL

. When I was twelve and still living in Ohio, some girls invited me to play truth or dare. We went to a barn with a haystack, the perfect setting. Little by little, we dared each other to undress. The Southern Comfort we were drinking out of a mason jar bolstered our courage. The game was going well when suddenly a big muscular guy, a high school senior, showed up and decided to fuck one of the girls in full view of all of us. The girl was willing but the party was ruined. None of us wanted to be there.

Turned out that the same dude rode the bus with me every day to school. One day he invited me to his house. This is a memory I suppressed until only a few years ago when, in rehab, it came flooding back. Therapy will do that to you.

The dude raped me.

It was quick, not pleasant. I was too scared to tell anyone.

“Tell anyone,” he warned, “and you’ll never have another friend in this school. I’ll ruin your fuckin’ reputation.”

What do you do with that fear? That pain? How do memories get suppressed, and where do they go to hide?

INNOCENCE VERSUS CORRUPTION

.

Hope versus despair.

I had the hope that comes with being a kid with natural athletic ability. In baseball, I had only one pitch—a fastball—but hardly anyone could hit it. By the eighth grade, I was able to launch a football fifty yards. The summer before my freshman year, I practiced with the team every day and achieved my goal: I was tapped as starting quarterback.

I was haunted by a dream that, decades later, still recurs:

I’m in the huddle, call the play, get the snap, drop back to pass, survey the field, and see, thirty yards away, my wide receiver two steps ahead of his defender. I cock my arm, and, just when I’m ready to launch a rocket, the football slips out of my hand for no reason. A lineman recovers the fumble and the game is lost.

What everyone wanted for me

Despite some obvious fears, I was a good athlete. I had a certain wholesome outlook on life. Look at the posters in my room: the famous Farrah Fawcett bathing-suit pose, pictures of badass boxers like Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Sugar Ray Leonard, and Thomas “Hitman” Hearns. I was the All-American Ohio boy with a far-off dream of playing for Notre Dame, just as Dad Dave had done.

I wanted the prestige and attention that came with being QB—not to mention the thrill that comes with being the field general. I thrived on competition.

When it came to music, I also had a California-Ohio hip-square split. My first LPs were

The Captain and Tennille’s Greatest Hits

and Elton John’s

Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy

. I was unapologetic in my passion for Tennille’s version of “Love Will Keep Us Together,” one of Neil Sedaka’s best songs. In Ohio, my mother developed a love for John Denver’s music that, according to her former husband’s new wife, Martha, was a sign of squareness. As a member in good standing of the square Cleveland burbs, I joined the school choir. Riding in the back of my parents’ Cadillac, I listened to

Peter and the Wolf

by Sergei Prokofiev, visualizing the animals depicted by the clarinet, oboe, horns, and bassoon.

I got religion.

I would wander over to Chagrin Falls Parks. The people who lived there, almost exclusively black, called it “The Park.” I liked that neighborhood and, in fact, in the sixth grade I had a crush on a beautiful black girl.

In my preteen years, I had developed a deep and abiding love of God, inspired by the ministry of Father Plato and Father Trevisin. Dave brought us into the Catholic fold. My mother had been Episcopalian but felt comforted by the progressive view of Christ afforded by these two gentle priests. It wasn’t about fire and brimstone, guilt or punishment. It was about a compassionate and patient love that doesn’t judge, scorn, or scold. “Be not afraid. I go before you always. Come follow me and I will give you rest.” I related to the notion of a mystic, all-accepting, all-forgiving love. I wanted it.

I became an altar boy. I wore the robes. During Mass, I brought the wine and the host to the priests. I lit the candles. Today, no matter where I am—tour bus, hotel room, studio, cabin in the woods—I light the candles. They calm me, center me, remind me of a time when God sat in the center of my heart. Not that He’s ever disappeared. The candles bring Him back. I need to light them, every day and every night.

I WAS BURNING BRIGHTLY IN CLEVELAND.

As a freshman, my first game at quarterback was only weeks away. I couldn’t wait. I smelled triumph; I longed for glory. And then, just like that, Dave made the announcement: I wouldn’t be playing the game; I wouldn’t even be going to that school. I’d be leaving my best friend, Rich Remias, who came over practically every night to play Dungeons & Dragons. Like me, Rich came from a broken home; he understood me. It hurt to leave Rich, but there was nothing I could do. We were moving, and we were leaving immediately. We were winging our way back to California. I didn’t know what to think. Didn’t know what to feel. I was fourteen.

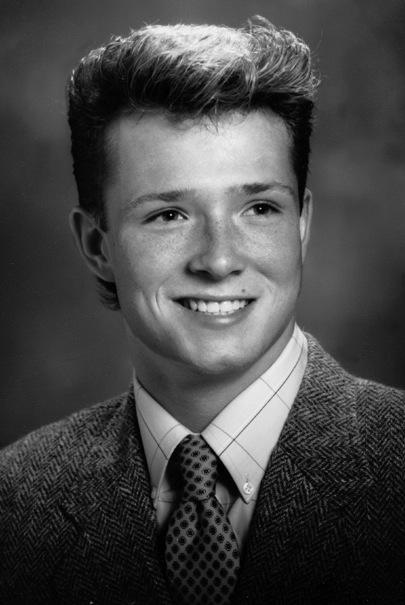

Senior class picture. Ahh, such a nice kid. Too bad in three years I’d be a strung-out junkie.

1982

.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, SURF CITY.

Orange County, bastion of reactionary Republicanism but also stronghold of punk-rock counterculture.

Our house was three blocks from the beach and directly across from Edison High, scene of my new life.

First thing I did was hand a note to the football coach. It was a message from my old coach that said I was a starting QB. The new coach wasn’t overly impressed. I was five eleven and weighed 155 pounds. The Edison team had won several championships. I’d have to wait.

By sophomore year I was one of the rotating quarterbacks. I also played defense. Going for an interception, I was speared from behind and knocked out of commission for a couple of weeks. I took that time to consider the options. I could keep playing, but without much of a chance to start at QB because, I always thought, my parents weren’t doling out money to the boosters’ club, or I could try something else. Rock-and-roll, like a siren song, was calling to me.

I met Cory Hickok on the football team. He played tight end but, more important, he played guitar in his big brother’s punk band, Awkward Positions. Cory turned me on to punk. In Ohio, I knew about Devo. I had listened to the Sex Pistols, whose

Never Mind the Bollocks

was our generation’s

Exile on Main Street

. But Cory played me the Clash. He played me Sweet. He introduced me to Echo and the Bunnymen. I can’t tell you how many times we listened to Queen’s

Sheer Heart Attack

, a cool power-poppunk hybrid. Cory had great ears and great taste.

He was over six feet and bone thin. Cool and quiet. A true-blue dude, he was a loving guy from a Christian family. Because my folks trusted his parents, I’d tell them I was staying at Cory’s whenever I went out to party. Cory was also a good artist. I admired his drawings and how he looked at life artistically. I had other hipster friends on the football team like Rich Smith, the guy who helped me upgrade my surfing and scamming skills. Rich was the first guy I heard refer to girls as “birds” and “chicks.”

AT SCHOOL, I WAS ACTIVE IN THE CHOIR AND SPORTS

—wrestling, volleyball, soccer, football. My stepdad, diligently working till all hours, never attended my football games. Meanwhile, I was attracted to a flourishing alternative-music scene. Shaped by the sounds of Social Distortion, hard-core postpunk big-beat garage bands were popping up everywhere. But I was not impressed with what I heard in the local clubs. I thought I could do better. I formed a postpunk band.