Not Dead & Not For Sale (3 page)

Read Not Dead & Not For Sale Online

Authors: Scott Weiland

W

HY IS THE WORLD SO DIFFERENT NOW

? I used to take my fishing rod and go down to the lake by myself. Now the world is one organized playdate after another.

In my childhood, I relied on my imagination—I could walk in the woods and be in Camelot, or Narnia, or wherever my mind envisioned. I had a vivid imagination, and still do. Today, though, how can you compete with a computer that, with the touch of a button, gives you every answer to every question?

In a technologically more innocent era, I was born Scott Kline in Santa Cruz, California, on October 27, 1967, to Sharon and Kent Kline, who divorced when I was two. Then Mom married Dave Weiland and I became Scott Weiland. I lost my name. I lost my father. I gained another father. Later I resented the hell out of my blood father, Kent, for not insisting that I keep his name. I felt abandoned.

Gave his name away, gave his son away

. Meanwhile, I saw Kent as a cool dude who drove a Pepsi truck for a living but smoked dope at night and listened to the Doors and Merle Haggard. When I think about my dad and Martha, the artist he married after Mom, I hear Fleetwood Mac’s

Rumours

. Kent’s the father I wanted to be with. At age forty-two, I’m still looking to connect with him.

My new dad was a good guy whose middle name was discipline. An aeronautics engineer with TRW Space and Electronics, he was always working on advanced degrees. Shortly after he married Mom, he moved us to Chagrin Hills, a woodsy suburb outside Cleveland, Ohio.

I’m stuck on that name—

Chagrin Hills. Chagrin

means distress, pain, anxiety, sorrow, affliction, mental suffering. Usually, idyllic suburbs have names like Pleasant Valley or Paradise Falls. Chagrin Falls makes no sense. In some ways, my childhood made good sense; in other ways, it didn’t.

My childhood was green pastures and bee stings, learning to play baseball and football, living in a nice house, waiting—always waiting—for the start of summer so I could go to California and see my dad Kent.

I was already a teenager when this dream started recurring. Its form changed slightly, but the basic structure stayed the same:

Posters are plastered all over the city—on billboards and buses, in splashy newspaper ads and screaming TV commercials. It’s all over the radio and the Internet. It’s tonight, it’s now, it’s what the world’s been waiting for.

It’s the ultimate Battle of the Bands.

Midnight tonight at a great outdoor stadium. The witching hour. The dark night of the soul. The moment of truth.

It’s three years before I’m born.

Or maybe it’s the year of my birth, or the moment of my birth.

Or maybe I’m three years old. Or five. Or ten.

Whatever my age, I’m there. I’m involved. I’m engaged. I’m riveted by the battle. My life is at stake.

My pulse is racing, my heart pounding inside my chest. The excitement has me crazy with anticipation.

Two bands. Two bandstands.

The Rolling Stones versus the Kingston Trio.

Over the Stones flies a pirate flag. Over the Kingston Trio flies the stars and stripes.

Chaos versus Order.

Nihilism versus Responsibility.

Crooked versus Straight.

The crowd fills the stands.

Half of them are fraternity boys and sorority girls, suits and dresses, blazers and loafers. The other half are freaks, punks, dopers, bikers, renegades.

I’m sitting in the dugout next to my mom.

My father is introducing the Stones. He and Keith are dressed identically in psychedelic bell-bottoms. He and Mick are sharing a joint. He calls the Stones “the greatest rock-and-roll band in the world.”

My stepdad introduces the Kingston Trio. They’re all wearing button-down blue oxford shirts and neatly pressed khaki trousers. My stepdad says, “This is real music. This is harmony. This is beauty.”

My father shouts over to him, “This is darkness! This is the real shit!”

“Go out there,” my mom whispers in my ear. “Go out there and help.”

I run out onto the field. I look up and see a hundred thousand screaming people. The bands have started playing simultaneously. Riffs of “Satisfaction.” Riffs of “Tom Dooley.” I run toward my dad, Kent, but he’s disappeared into the crowd. Mick and Keith don’t know me. Security is chasing after me. I’m chasing after my dad, but I can’t find him. I’m running up and down, running all over the stadium, but I can’t find him, can’t find him, crying hysterically, I can’t find my dad …

FATHERS AND SONS, SONS AND BROTHERS.

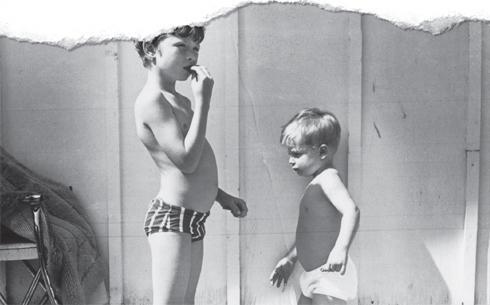

My brother, Michael, was born to my stepfather and my mother when I was four and a half. On the day Mom came home from the hospital, I remember bright sunshine lighting our house. When I saw my baby brother, I was filled with wonder. He was fast asleep; he looked helpless, adorable, more doll-like than human. Whenever he squeezed my finger with his tiny hand, I felt flooded with love. I wouldn’t feel that kind of pure love until the birth of my own children. For the first time in my life, instead of worrying about being protected, I had someone to protect.

Me and Michael

The Scott-and-Michael story centers on two brothers to whom God gave musical talent. I’m the one who sought success; he’s the one who feared it. We both fell into drink and drugs. When I got caught with a beer, our stepdad brought the wrath of the gods down on my head. When Michael got caught with pot, he said, “It’s God’s herb,” and Father Dave just sort of shook his head. Maybe the wrath did me good. Maybe the tolerance did Michael harm. Later, I gave Michael his first beer, his first shot of dope, his first hit of crack. Do I feel guilty about that? Yes and no. I wish I hadn’t made those introductions, but knowing Michael, he would have done anything anyway—just to get away. Michael was always way ahead of the curve.

Camping—hippy-style—a little weed and Big Foot: me at age six, cousin Chris, and Craig, 1973

In the lane the snow is glistening: my childhood house in Cleveland

T

WO STATES OF MIND:

Ohio and California. Ohio is cold and square; California is cool and hip. At least in the mind of a kid.

THE BEER BUZZ IS A SMALL BUZZ

, but it’s an intriguing buzz if you’re looking for any kind of buzz. In the sixth grade, living in Cleveland, I lived for the summertime. Summertime meant California and my dad, Kent, and his wife, Martha. Summertime meant watching them cultivate their pot plants in the backyard and throwing their parties with Emmylou Harris and Stones records and margaritas and shots of Cuervo Gold. Summertime meant pals like Billy, a cool dude who already had long hair, Levi’s super-bell cords, and Vans slip-ons. Billy was the first guy I met who played guitar. He taught himself Zeppelin and taught me about a beer buzz. Billy, my stepbrother, Craig, and Jonathan, the son of Martha’s best friend, snuck beers out of Dad’s fridge. While the grown-up party was building its own buzz, we chugged down the brews, and then another, and another, and walked out into the backyard, the secret inside our heads. I liked the feeling of entering an alternate energy field. I liked the psychological and chemical rearrangement brought on by the alcohol.

Other times we invaded Dad’s liquor cabinets: times when Billy, Craig, Jonathan, and I got sick, times when we pushed the envelope and smoked weed, which hit me like acid. I tripped on the sunlight streaming through a trellis fence. The pattern of shade became a three-dimensional revelation, a maze containing the very mystery of life, a key connecting all feelings to all forms.

Back in Cleveland for the seventh grade, the California sunshine was replaced with the Ohio snow. My Ohio friends weren’t as cool as Billy. My Ohio extracurricular activities centered on sports. Breaking tackles. Wrestling and fishing. Getting up at six a.m. in the dark for swimming practice and going at it again after school.

One day I came home from school and walked over to my friend Mark’s house. His parents, who worked late, had a killer liquor cabinet. Over ice, I filled a tumbler with Black Velvet, gin, and vodka, took it to the woods, sat against a tree, and drank it down. The moment was pivotal precisely because it was solitary. I got blasted all alone. The isolation did something to me—removed me from life and reality—that I experienced as strangely wonderful.

The winter was long. I studied the calendar, watching the months slowly pass until fall gave way to winter, winter to spring, and spring to summertime back in California, where I learned to surf. I wasn’t a champ, but I could do it. While surfing I felt free from time, suspended in space, thoughtless and alive.

HAVING TWO DADS AND NO DAD WAS CONFUSING

. I wanted my biological dad but he seemed to want me only during the summers. He was the one listening to Hank Williams. My stepdad was telling me to do my homework. Meanwhile, the teachers told my stepdad that I was smart but hyper. I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. Psychologists suggested that I go on Ritalin. Mom wouldn’t allow it. But she would allow me to visit her ex-husband at the end of the school year. So I was off to California to visit Dad and Martha and Martha’s son, Craig, who was my age. Craig was a great guy and one of my closest friends, but I couldn’t help but be a little jealous of him. He had my dad’s attention all the time. Craig had become my replacement. Then two years later, Craig was dead.

Me hugging Craig

I REMEMBER SITTING IN MR. BURKE’S

creative-writing class. Mr. Burke was my favorite teacher. The school year was almost over. I was still in shock. I still couldn’t process the news. Mr. Burke knew what happened back in California. He told me to write about it. He said writing would help. I remembered then—and still remember now—every moment, every conversation that took place between me and Craig. Our encounters were etched into my psyche.

I wrote this:

“Yesterday was rainy. The sky was crying rain. I was standing at the end of our driveway when I heard my mother’s voice. She said, ‘Hurry, Scott, there’s a call for you.’ I ran in the house. My heart was beating like crazy. I knew something was wrong. My father’s voice sounded different. His voice was crying pain.”

From there, I wrote another ten pages, raw words flowing out of the ink like a bad, black dream.

I turned in the paper and the teacher understood. That’s all I could write. I’d memorized my father’s words, but couldn’t repeat them: “Craig was riding a wheelie. You know how he’s the best wheelie rider around. He didn’t see the car coming. It hit him head-on. His brain is swelling. There’s a hole in his brain. They’re operating tonight.” I couldn’t repeat what my father said when he called the next morning: “Craig’s dead.” I couldn’t describe my memories of how, for week after week, month after month, year after year, Dad would take me and Craig dirt-bike riding.

I couldn’t say anything when I visited Dad that summer. He was completely remote and removed from me. I couldn’t tell him—couldn’t tell anyone—about the feelings overwhelming me. I was angry, guilty, sad, resentful, longing to have my father back. I was covered with confusion.

FATHERS AND SONS, SONS AND BROTHERS.

Craig was my brother, and even though he wasn’t Dad’s blood son, I know that when Craig died, part of Dad died with him. That’s a part of my father I’ve never been able to reach. Much later in life when my brother Michael died, part of me disappeared and has never returned. It hurts to love.

Leaping for the stars