On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (2 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

Introduction to the Paperback Edition

If you are a virgin preparing for your wedding night, if you or your partner are having sexual difficulties, or if you are just curious

. . . then there are hundreds of scholarly books available to you on the topic of sexuality. But if you are a young "virgin" soldier or law-enforcement officer anticipating your baptism of fire, if you are a veteran (or the spouse of a veteran) who is troubled by killing experiences, or if you are just curious . . . then, on

this

topic, there has been absolutely nothing available in the way of scholarly study or writing.

Until now.

Over a hundred years ago Ardant du Picq wrote his

Battle Studies,

in which he integrated data from both ancient history and surveys of French officers to establish a foundation for what he saw as a major nonparticipatory trend in warfare. From his experiences as the official historian of the European theater in World War II, Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall wrote

Men Against Fire,

in which he made some crucial observations on the firing rates of men in war. In 1976 John Keegan wrote his definitive

Face of

Battle,

focusing again exclusively on war. With

Acts of War,

Richard Holmes wrote a key book exploring the nature of war. But the link between killing and war is like the link between sex and relationships. Indeed, this last analogy applies across the board. All previous authors have written books on relationships (that is, war), while this is a book on the act itself: on killing.

These previous authors have examined the general mechanics and nature of war, but even with all this scholarship, no one has looked into the specific nature of the act of killing: the intimacy xiv I N T R O D U C T I O N TO THE PAPERBACK E D I T I O N

and psychological impact of the act, the stages of the act, the social and psychological implications and repercussions of the act, and the resultant disorders (including impotence and obsession).

On

Killing

is a humble attempt to rectify this. And in doing so, it draws a novel and reassuring conclusion about the nature of man: despite an unbroken tradition of violence and war, man is not by nature a killer.

The Existence of the "Safety Catch"

O n e of my early concerns in writing

On Killing

was that World War II veterans might take offense at a book demonstrating that the vast majority of combat veterans of their era would not kill.

Happily, my concerns were unfounded. N o t one individual from among the thousands w h o have read

On Killing

has disputed this finding.

Indeed, the reaction from World War II veterans has been one of consistent confirmation. For example, R. C. Anderson, a World War II Canadian artillery forward observer, wrote to say the following:

I can confirm many infantrymen never fired their weapons. I used to kid them that we fired a hell of a lot more 25-pounder [artillery]

shells than they did rifle bullets.

In one position . . . we came under fire from an olive grove to our flank.

Everyone dived for cover. I was not occupied, at that moment, on my radio, so, seeing a Bren [light machine gun], I grabbed it and fired off a couple of magazines. The Bren gun's owner crawled over to me, swearing, "Its OK for you, you don't have to clean the son of a bitch." He was really mad.

Colonel (retired) Albert J. Brown, in Reading, Pennsylvania, exemplifies the kind of response I have consistently received while speaking to veterans' groups. As an infantry platoon leader and company commander in World War II, he observed that "Squad leaders and platoon sergeants had to move up and down the firing line kicking men to get them to fire. We felt like we were doing good to get two or three m e n out of a squad to fire."

I N T R O D U C T I O N TO THE PAPERBACK E D I T I O N XV

There has been a recent controversy concerning S. L. A. Marshall's World War II firing rates. His methodology appears not to have met modern scholarly standards, but when faced with scholarly concern about a researcher's methodology, a scientific approach involves replicating the research. In Marshall's case, every available parallel scholarly study replicates his basic findings. Ardant du Picq's surveys and observations of the ancients, Holmes's and Keegan's numerous accounts of ineffectual firing, Holmes's assessment of Argentine firing rates in the Falklands War, Griffith's data on the extraordinarily low killing rates among Napoleonic and American Civil War regiments, the British Army's laser reenactments of historical batlles, the FBI's studies of nonfiling rates among law-enforcement officers in the 1950s and 1960s, and countless other individual and anecdotal observations all confirm Marshall's conclusion that the vast majority of combatants throughout history, at the moment of truth when they could and should kill the enemy, have found themselves to be "conscientious objectors."

Taking Off the Safety Catch

Slightly more controversial than claims of

low

firing rates in World War II have been observations about

high

firing rates in Vietnam resulting from training or "conditioning" techniques designed to enable killing in the modern soldier. From among thousands of readers and listeners, there were two senior officers with experience in Vietnam who questioned R. W. Glenn's finding of a 95 percent firing rate among American soldiers in Vietnam. In both cases their doubt was due to the fact that they had found a lack of ammunition expenditure among some soldiers in the rear of their formations. In each instance they were satisfied when it was pointed out that both Marshall's and Glenn's data revolved around two questions: "Did you see the enemy?" and "Did you fire?" In the jungles of Vietnam there were many circumstances in which combatants were completely isolated from comrades who were only a short distance away; but among those who did see the enemy, there appears to have been extraordinarily consistent high firing rates.

xvi I N T R O D U C T I O N TO THE PAPERBACK E D I T I O N

High firing rates resulting from modern training/conditioning techniques can also be seen in Holmes's observation of British firing rates in the Falklands and in FBI data on law-enforcement firing rates since the introduction of modern training techniques in the late 1960s. And initial reports from researchers using formal and informal surveys to replicate Marshall's and Glenn's findings all indicate universal concurrence.

A Worldwide Virus of Violence

The observation that violence in the media is causing violence in our streets is nothing new. The American Psychiatric Association and the American Medical Association have both made unequivocable statements about the link between media violence and violence in our society. The APA, in its 1992 report

Big World, Small

Screen,

concluded that the "scientific debate is over."

There are people who claim that cigarettes don't cause cancer, and we know where their money is coming from. There are also people who claim that media violence does not cause violence in society, and we know which side of

their

bread is buttered. Such individuals can always get funding for their research and are guaranteed coverage by the media that they protect. But these individuals have staked out the same moral and scientific ground as scientists in the service of cigarette manufacturers.

On Killing's

contribution to this debate is its explanation as to

how

and

why

violence in the media and in interactive video games is causing violence in our streets, and the way this process replicates the conditioning used to enable killing in soldiers and law-enforcement officers . . . but without the safeguards.

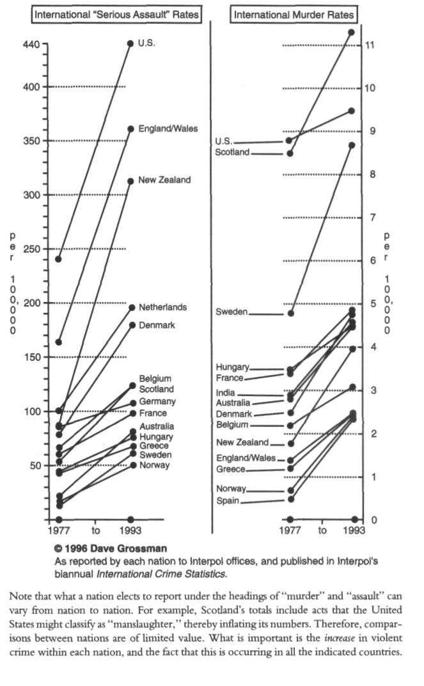

An understanding of this "virus of violence" must begin with an assessment of the magnitude of the problem: ever-increasing incidence of violent crime, in spite of the way that medical technology is holding down the murder rate, and in spite of the role played by an ever-growing number of incarcerated violent criminals and an aging population in holding down the violence.

It is not just an American problem, it is an international phenomenon. In Canada, Scandinavia, Australia, New Zealand, and all across Europe, assault rates are skyrocketing. In countries like India,

I N T R O D U C T I O N TO THE PAPERBACK E D I T I O N xvii

XViii

I N T R O D U C T I O N T O THE PAPERBACK E D I T I O N

where there is no significant infrastructure of medical technology to hold it down, the escalating murder rate best reflects the problem.

Around the world the result is the same: an epidemic of violence.

How It Works: Acquired Violence Immune Deficiency

When people become angry, or frightened, they stop thinking with their forebrain (the mind of a human being) and start thinking with their midbrain (which is indistinguishable from the mind of an animal).

They are literally "scared out of their wits."

The only thing that has any hope of influencing the midbrain is also the only thing that influences a dog: classical and operant conditioning.

That is what is used when training firemen and airline pilots to react to emergency situations: precise replication of the stimulus that they will face (in a flame house or a flight simulator) and then extensive shaping of the desired response to that stimulus. Stimulus-response, stimulus-response, stimulus-response. In the crisis, when these individuals are scared out of their wits, they react properly and they save lives.

This is done with anyone who will face an emergency situation, from children doing a fire drill in school to pilots in a simulator.

We do it because, when people are frightened, it works. We do not

tell

schoolchildren what they should do in case of a fire, we

condition

them; and when they are frightened, they do the right thing. Through the media we are also conditioning children to kill; and when they are frightened or angry, the conditioning kicks in.

It is as though there were two filters that we have to go through to kill. The first filter is the forebrain. A hundred things can convince your forebrain to put a gun in your hand and go to a certain point: poverty, drugs, gangs, leaders, politics, and the social learning of violence in the media — which is magnified when you are from a broken home and are searching for a role model. But traditionally all these things have slammed into the resistance that a frightened, angry human being confronts in the midbrain. And except with sociopaths (who, by definition, do not have this resistance), the vast, vast majority of circumstances are not sufficient to overcome this midbrain safety net. But if you are conditioned I N T R O D U C T I O N TO THE PAPERBACK E D I T I O N xix to overcome these midbrain inhibitions, then you are a walking time bomb, a pseudosociopath, just waiting for the random factors of social interaction and forebrain rationalization to put you at the wrong place at the wrong time.

Another way to look at this is to make an analogy with AIDS.

AIDS does not kill people; it simply destroys the immune system and makes the victim vulnerable to death by other factors. The

"violence immune system" exists in the midbrain, and conditioning in the media creates an "acquired deficiency" in this immune system. With this weakened immune system, the victim becomes more vulnerable to violence-enabling factors, such as poverty, discrimination, drug addiction (which can provide powerful motives for crime in order to fulfill real or perceived needs), or guns and gangs (which can provide the means and "support structure"

to commit violent acts).

Canada is an example of a nation that we have always considered to be relatively crime-free and stable. Stringent gun laws, comparatively intact family structure, beloved and paternalistic government.

But (surprise!) Canada has the exact same problem that we do.

According to the Canadian Center for Justice, since 1964 the number of murders has doubled per capita, and "attempted murders" increased from 6 per million in 1964 to 40 per million in 1992. And assaults went up from 209 per 100,000 in 1964 to 940

per 100,000 in 1992. This is almost exactly the same ratio as the increase in violent crime in the United States. Vast numbers of Canadians have caught the virus of violence, the "acquired violence immune deficiency," and as they ingest America's media violence, they are paying the inevitable price.

This process is occurring around the world in nations that are exposed to media violence. The one exception is Japan.

If you have a destroyed immune system, your only hope is to live in a "bubble" that isolates you from potential contagions.

Japan is an example of a nation living in a "violence bubble." In Japan we see a powerful family and social structure; a homogeneous society with an intact, stable, and relatively homogeneous criminal structure (which has a surprisingly "positive" group and leadership influence, at least as far as sanctioning freelancers); and an island

X X