Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (27 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

The

şeyhülislam's

religious ruling

(fetva emine)

which approved the deposing of Abdülhamid incorporated religious and civic models of legitimacy, bringing in the notions of just rule and public good as well as the will of the people:

QUESTION

: What should be done with a Commander of the Faithful who has suppressed books and important dispositions of the Sheriat law; who forbids the reading of and burns such books; who wastes public money for improper purposes; who, without legal authority, kills, imprisons, and tortures his subjects, and commits other tyrannical acts; who, after he has bound himself by oath to amend, violates such oath, and persists in sowing discord, so as to disturb the public peace, thus occasioning bloodshed? From various provinces the news comes that the population has deposed him; and it is shewn that to maintain him is manifestly dangerous, and his deposition advantageous. Under such conditions is it permissible for the actual governing body to decide as seems best upon his abdication or deposition?

RULING:

It is permissible [olur].

134

As well, much of the Ottoman popular press fully supported the deposition of the sultan. The Islamic reformist newspapers

The Lighthouse

and

Crescent (Hilal)

approved of the

fetva-emine

on the grounds that Abdulhamid II, as an unjust ruler, had not ruled according to Islamic principles.

The Lighthouse

fully supported the

fetva

and gave its own extensive textual support for the decision, and

Crescent

opined: “Let each true Mussulman [sic] rest convinced that, in virtue of the Sheriat and the holy laws of the Koran, Abd-ul-Hamid can never have been the real Caliph of the Believers. All those that can see in Abd-ul-Hamid the real Caliph are quite ignorant of the laws of the Sheriat or else act in opposition to them.”

135

When the sultan's half-brother Mehmet Reşat (also known as Muhammad V) was installed as sultan in April 1909, the office of the sultan was transformed into yet another element fully subject to the nation itself. In his formal remarks upon ascending the throne, the sultan reportedly addressed his fellow citizens, saying that he hoped to work for the nation's success and happiness, and that “since the nation has already chosen me today,” he would serve it faithfully.

136

In fact, by that point, a mere nine months after the revolution, that was more or less the understanding

shared by many of his fellow citizens. In terms that would have been unprecedented before, David Yellin pronounced the new sultan “is not the one who grants freedom to the nation (as if urriyya

urriyya

is a thing to be bought or granted), but it is the nation who granted the sultan its voluntary compliance.”

137

Part-invitation, part-warning, the newspaper

Sabah

in Istanbul informed the new sultan of the duties of a constitutional monarch: “The constitution forbids absolutism and the arbitrary will of the sovereign. But it does not prevent him from working for the greatness of his nation. He is

millet babasi

, “the father of the nation,” and it behooves him to act as one. The despot governs through fear, the constitutional monarch governs through affection. It is his duty to earn the affection of the nation which is master of his destinies.”

138

This radical view had taken divergent notions of “liberty” to challenge the sultan's legitimacy, one important step in the transformation of the relationship between Ottoman citizens and their government.

There is perhaps no greater marker of the power and importance of the press in the Ottoman revolution than the fact that during the spring 1909 counterrevolutionary coup—essentially ten days of rioting in Istanbul by low-level soldiers and

softajis

(religious seminary students) who were reportedly paid off with gold from the sultan’s coffers—the offices of two newspapers, the official CUP organ

şura-yi Ümmet

and the pro-CUP

Tanin

, were ransacked and destroyed. One journalist who published regularly in

Tanin

, the noted female author Halide Edib Adivar, described days spent in hiding until her daring nocturnal escape on a steamer bound for Alexandria.

1

In the capital and in the provinces, the multilingual press had become a central site for an emergent revolutionary public sphere whose primary task was the deeply public process of endowing Ottomanness with meaning. Rather than passively recording events or words or simply transmitting information and knowledge, newspapers played a much more productive role in constituting and articulating the public imperial self. Newspaper editors had very strong ideas that they conveyed to their readers with missionary zeal. The Beirut-based newspaper

Ottoman Union

, for example, saw itself as the mouthpiece

of

the people, reflecting their “authentic” wishes and desires, at the same time that it took it upon itself to be a mouthpiece

to

the people, educating and enlightening them to the requirements of a changing world.

2

In other words, the press would serve as the handmaiden of the revolution, carrying out its aims of reforming and reviving the Ottoman Empire by showing its readers—the Ottoman public—what it meant to “be Ottoman” at a time of rapidly changing political and social realities.

3

In order to accomplish this, first and foremost the press consciously took upon itself the task of promoting Ottoman unity and citizenship practices across ethnic, religious, and linguistic boundaries. As

Ottoman

Union

stated in that same article, “The Ottoman state is comprised of many groups and it is incumbent upon us to strive to publish newspapers composed of the elite of the groups present in the Ottoman lands until true synthesis [

al-tā’līf al- aqīiīq

aqīiīq

] and true devotion are attained, and until the editors will possess the trust of the people and their consent.” We have also seen, in the

previous chapter

, that the press played a self-appointed role in educating Ottomans to their new political and social roles as imperial citizens.

Newspapers appeared in Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Ladino, Bulgarian, and Hebrew, to name just a few of the languages of the empire. However, these newspapers did not represent autonomous publics: some readers were undoubtedly multilingual and had access to newspapers in several languages, and many newspapers translated articles that had appeared in other local languages for the benefit of their broader readership. These translations could be simply informative or aimed at serving the Ottomanist vision, but they just as easily could promote intercommunal rivalry. As we will see in the Palestinian press, complaints about the relative standing or privileges of another community found their way to a large number of readers and listeners through the press. As a result, the press in this period served not only to help “imagine” the community in universally inclusive imperial terms, but also increasingly in exclusionary sectarian and ethnic terms. Stated differently, at the same time that the press was a vehicle for creating and underscoring new forms of centripetal solidarity, it

also

became a new platform for expressions of centrifugal tensions and rivalries.

MAKING NEW READERS

Even before the advent of the press, Ottoman residents had access to numerous sources of information as well as sites for public discourse, whether it be the neighborhood crier or written announcements posted on city walls and squares, formal announcements in mosques, synagogues, and churches, or informal gossip in coffeehouses, markets, and social gatherings.

4

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the emergence of a semi-independent press, the rise in education, new civil-society institutions, and the role of the city in creating an urban citizenry all contributed to the undeniable existence of a vibrant public sphere of discourse and debate in many corners of the empire.

5

The first independent newspaper in Ottoman Turkish had appeared in 1860; by 1876 a total of forty-seven papers were being published in Istanbul alone—thirteen in Ottoman Turkish, nine in Armenian and Greek each, seven in French,

three in Bulgarian, two in Hebrew and English each, one in German, and one in Arabic.

6

It is impossible to overstate the impact of this first wave of press and publishing on the intellectual and social life of the Ottoman Empire. We have already seen in

Chapter One

the important role that early newspapers played as a platform for the opposition of the Young Ottomans. Newspapers like

Vakit

and

Istikbal

published daring commentaries on the sovereignty of the people and the contingency of the sultan, and the emerging satirical press also contributed to fostering debate and political criticism, at least until the 1864 and 1867 press laws clamped down on this sort of journalism and forced it abroad. Despite growing government censorship, the early newspapers seem to have enjoyed vast popularity; one estimate places the circulation figures for the important paper

Tasvir-i Efkar

at twenty thousand. More important to the circulation of ideas than individual subscribers, however, were the dozens of bookshops and “reading rooms”

(kiraathaneler)

in Istanbul, where educated men could access and discuss the latest publications.

7

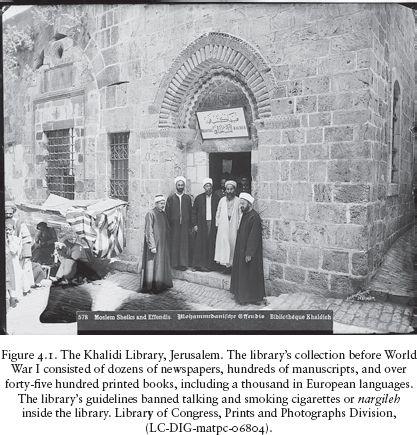

This vibrant life of the mind was not limited to the imperial capital alone. Salonica, Izmir, and Beirut were also important centers for publishing, and the circulation of journals as well as books was widespread. Literate Palestinian men also tapped into these broader imperial and regional currents; as partial evidence, one scholar has counted over one hundred letters to the editor from Palestine to two different Cairene newspapers in the last decade of the nineteenth century alone. These readers accessed the press and other publications either by subscription or, much more likely, through important urban institutions like the Khalidi Library or the library of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, both of which had holdings of dozens of regional newspapers and magazines, and thousands of books. At the same time, even the

shaykh

of the tiny Palestinian village of Yarka, Marzuq Ma‘addi, had subscriptions to at least four different newspapers in the 1880s and 1890s, underscoring the fact that the press was not solely an urban, elite phenomenon.

8

And yet, due to the strict limitations of the Hamidian regime on public life (censorship, limitations on public gatherings and organization) as well as the political impotence of the average Ottoman subject, the connection of the Ottoman public sphere to political action was highly constricted. In other words, Ottomans could read about events taking place around their empire and the world, but they could do little about it—in contrast to the situation in contemporary Egypt and Qajar Iran, where the press was an important platform for political mobilization.

9

With the revolution of 1908, however, the Ottoman public sphere was radically transformed both in scale and in scope.

With the news that the constitution was being restored and that the strict censorship laws were being lifted, the press in the Ottoman Empire virtually exploded: one scholar has characterized the journalistic reaction to the revolution throughout the empire as “immediate and powerful, like the rush of a great river upon the collapse of a large dam.”

10

Indeed, over two hundred new publications appeared in Istanbul alone in the year after the revolution. A similar wave of new journals overtook the rest of the empire’s important provinces and urban centers: in the provinces that comprise today’s Iraq, whereas before the revolution only official newspapers were published in the provincial centers of Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul, after the revolution over seventy political, literary, and caricature newspapers entered the marketplace; in Aleppo, at least twenty-three new newspapers and journals appeared in the four

years following the revolution.

11

Likewise, within the half-year following the revolution, at least sixteen new Arabic newspapers emerged in Palestine, and by World War I, another eighteen Arabic newspapers had been established.

12

In addition to the booming Arabic press, several new Hebrew-language newspapers began appearing as well as three Ladino newspapers and at least one Greek newspaper.

Indeed, the lively public discussions we have seen in earlier chapters were facilitated by these new outlets, and a new audience was drawn to the press via the coffeehouses and the streets. Rather than simply being the private domain of urban elites, the late Ottoman press appealed to members of the new middle class, workers, women, children, and the rural populations.

13

According to a European visitor in Istanbul in those early months: “Every one was reading them—the very cabbies, waiting on the box of their broken-down little victorias, were drinking in the new learning—the knowledge of good and evil, of politics, of the things outside, of chancelleries, Parliaments, democratic movements, of the strife of nations, of their armies, their railways, their restless commerce, of all manners of strange amusements.”

14

A German archaeologist observed a similar proliferation of the newspaper on his 1914 trip to Syria and Palestine, where he saw “people eagerly reading newspapers in the streets, the railway stations, the houses and shops.”

15

Above all, however, the new revolutionary press emerged out of the

effendiyya

strata; precisely those Muslims, Christians, and Jews who had been educated in the preceding decades under new conditions were attuned to the changes taking place throughout the empire, hungry for new outlets of information and expression. A fascinating survey conducted in the coffeehouses of Istanbul in 1913 by an Ottoman youth studying political science at Columbia University reinforces this assessment: slightly over half of the 120 café-readers he interviewed were graduates of the new university programs in law, medicine, commerce, or military sciences, and another 20 percent were graduates of state high schools or lyceum. Most (113 of 120) bought and read newspapers on a regular basis, and many (72 out of 120) read two or more newspapers

per day

in addition to weekly and monthly periodicals. Overall, the Columbia student concluded that there was deep interest, high expectations, and a widespread influence of the press.

16

In Istanbul and the larger cities, circulation rates for the most popular newspapers could run in the tens of thousands.

17

In far less populous Palestine, however, it seems that the more popular newspapers had up to two thousand subscribers, with smaller newspapers having only three hundred to five hundred subscribers.

18

With local annual subscription rates between forty to seventy

kuruş

for an Arabic newspaper and around thirty

kuruş

for a Hebrew paper, they were certainly within the means of the salaried and independent middle classes. However, seeing how the average day laborer earned at best eight

kuruş

per day, it is unlikely that many workers could afford newspapers on other than the most sporadic basis.

19