Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (25 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

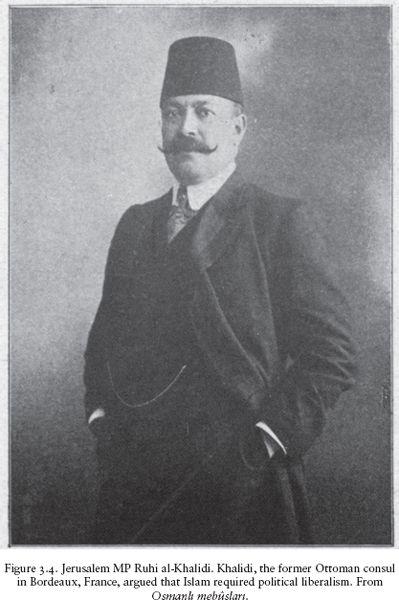

In the end, election results for the Jerusalem province were in favor of two Jerusalem notables and one Jaffan notable, all Muslims, all members of the Palestinian urban elite who had traditionally been involved in Ottoman government and Islamic religious offices: Ruhi al-Khalidi (with sixty second-tier electoral votes total); Sa'id al-Husayni (with fifty-nine electoral votes); and Hafiz al-Sa'id (with forty-seven total electoral votes).

97

With the exception of Hafiz al-Sa'id, the Palestinian representatives were relatively young, in their thirties and early forties, following the trend established by the Arab provinces in the 1876 parliament to send younger members of prominent local families.

98

All three had been government officials, but al-Khalidi, the former Ottoman consul in Bordeaux, France, was the only one of the three considered a “true liberal” ideologically in tune with the spirit of the revolution. Al-Husayni had been head of the education division in the Jerusalem provincial government, and al-Sa'id had served in various provincial offices throughout Palestine. In northern Palestine, two religious scholars were elected: Shaykh Ahmad al-Khammash of Nablus and Shaykh As'ad Shuqayri of ‘Akka.

99

The election results provide further evidence for the very deep ties between urban centers and their outlying hinterlands, as well as for the resilience of patronage networks fashioned by urban notables and rural leaderships. As one historian notes, “Ordinary voters deferred to community leaders who would presumably better judge the interests of the community.” Furthermore, the two-tier system itself “preserved and reinforced patronage relationships and precluded the election of candidates truly representative of the common people.”

100

In other words, while self-made individuals like lawyers, doctors, and journalists could and did

run for election, oftentimes in the end those who were elected had the backing of family connections and strong social and political networks, in addition to years of government service, behind them.

The Sectarian Prism III: Ethnic Politics

Despite the Ottomanist moment represented by the parliamentary elections, it is clear that some individuals and groups within the empire expected the parliament to be a platform, not simply for broader Ottoman reforms, but more important, for the airing of communal agendas. This was expressed by one Zionist correspondent for the Jerusalem Jewish newspaper

The Deer

, Ya'kov Friman, who argued:

The people, through its representatives, can turn to the government and demand the reforms needed for the country's material and spiritual elevation. Not only that, but each nation that lives in the empire can send its representatives to parliament to demand its rights living in a united empire…. The more complete freedom will give each of the peoples room to develop in its own communities and according to its inclination. Political unity of the peoples of Ottomania does not mean assimilation: it does not mean to forget one's future and turn into someone else. This is harmful to the nation and does not contribute to the public good.

101

A similar view seems to have existed within the Greek Orthodox community, many of whom (including the patriarch) had pressed for proportional representation. In fact, unhappy with the elections results, thousands of Greeks protested the opening of the parliament demanding that the elections be voided in areas where Greeks were not elected; reflecting the lingering arrogance born of the Capitulations, one Greek who was arrested argued, “I am entitled to vote not because I am a citizen, but because I am a Greek.”

102

For those segments of the Ottoman population and for some European observers, the parliamentary results were worrying evidence of the Turkish, Muslim orientation of the new government. Of the parliament's 260 members, 214 (82 percent) were Muslims, 43 (16.5 percent) were Christians, and 4 were Jews. Ethnically, native Turkish speakers comprised 46 percent of the parliament (119 members), followed by Arabicspeakers at 28 percent of the parliament (72 members), as well as smaller numbers of Greek, Albanian, Kurdish, Serbian, Bulgarian, and Romanian speakers.

103

A visiting French deputy complained about the overall underrepresentation of Greeks and Armenians, starkest in the province of Edirne, which did not have a single non-Muslim among its nine elected representatives despite a sizable non-Muslim population.

104

As the historian Hasan Kayali has noted in a different region of the empire, “particularly after 1908, electoral politics animated and politicized protonationalist movements among the Muslims, while it also crystallized competing multiethnic agendas.”

105

While it is undoubtedly true that certain segments of the Ottoman population in some parts of the empire saw the elections as an opportunity for ethnic self-determination, we should be careful not to assign too much causal influence to the ethnic fragmentation of the empire. In 1908, it is clear, the special path viewed for the Arab provinces, more distant from imperial rule in Istanbul, was a question of decentralization rather than ethnic self-determination. MP Ruhi al-Khalidi said as much in his departure speech; after thanking the crowd for their support of the “holy homeland and freedom,” al-Khalidi laid out the broad-based reforms to be carried out through the parliament, first and foremost to lighten the “imperial burden” in the provinces in favor of decentralization. The desired reforms according to al-Khalidi included implementing an ambitious public works program, bringing running water, planting trees, increasing life expectancy, opening roads and train lines, expanding the educational system, forming new commercial agreements, and establishing a people's bank—all of which are administrative and infrastructure policy issues rather than a question of identity politics or self-determination.

106

Indeed, residents had very specific expectations that their representatives would bring utility and good works to the province. The editor of

Jerusalem

, Jurji Habib Hanania, appealed to his new representatives:

And now, oh gentlemen…yes you will be in the parliament not only as representatives of Jerusalem but rather as representatives of the entire Ottoman nation. I want to remind you in the name of our beloved city Jerusalem,…do not forget that the future of Jerusalem demands [much] from you two and we depend on you to teach the people our duties.

107

At the same time, as we have seen, the 1908 election did carry with it an element of communal rivalry. After the experience of the first elections, it was apparent that the Jewish and Christian communities were ill-prepared to exercise their political rights.

108

Christians and Jews were electorally weak due to the low numbers of Ottoman citizens as well as the low number of property taxpayers in both groups, they were disorganized and factionalized communally, and they were unwilling or unable to successfully build alliances across communal lines. In Levi's final analysis of the case of the Palestinian Jewish communities, “If we had known our own weaknesses and admitted them, then it would have been only half as bad, because we would have tried to team up with the other peoples. However we are convinced of the fact that Palestine comes to us as our birth right and we are the worse for it!”

109

The Hebrew newspaper

The Deer

saw the elections from the outset as a zero-sum game, referring to them on one occasion as “the war between the nations.” This would seem to be born out by a brief note in

The Deer

's report of the public farewell, which differed in significant ways from that which appeared in

Jerusalem.

In contrast to the Ottomanist, universalist portrait depicted by

Jerusalem, The Deer

emphasized that the majority of those gathered were Muslims and that there was a distinctly pro-Arab sentiment in the air.

110

According to the paper, ‘Abd al-Salam Kamal had called on the newly elected members of parliament to defend the Arabs' rights, followed by David Yellin, who spoke of the corresponding demands of the Jewish community. Afterward, the crowd fired pistols, waved swords, and cheered for “the Arabs.”

Whether or not

The Deer

's account is accurate is almost immaterial, for it reflects the ways in which the elections marked the entrance of a sanctioned sectarian element into postrevolutionary Ottoman politics that directly challenged the civic Ottomanist project. Rather than solely relying on their geographically designated representatives, non-Muslim groups imposed a neo

-millet

structure onto the parliament through which they sought help from members of parliament and senators belonging to their own ethno-religious groups. For example, the Jews of Palestine repeatedly appealed to the four Jewish members of parliament on various issues of particularistic Jewish interest, despite the fact that these representatives were from Salonica, Izmir, Istanbul, and Baghdad.

111

In addition to the Jewish members of parliament, the chief rabbi was another central address the Jews turned to for aid in dealing with the authorities, further illustrative of a neo-millet-civic hybridity.

112

KHALIDI, HUSAYNI AND SA'ID GO TO ISTANBUL

Despite these serious issues, the election controversies were quickly put to rest and the three southern Palestinian members of parliament were given elaborate populist sendoffs that celebrated the unity of Jerusalem's electorate in November 1908. Indeed, although the 1908 Ottoman parliamentary election left much to be desired in terms of absolute democratic as well as relative sectarian enfranchisement, it still marked a milestone in achieving local rights and reaffirming participation in the imperial endeavor. As one historian has written about emerging elections in nineteenth-century Latin America, “the rhetoric of representation displayed around the elections also had symbolic and ideological effects

that contributed to the circulation and reformulation of republican and democratic ideas on citizenship among the population.”

113

In the Ottoman Empire, the most significant feature of republican citizenship was the entrenchment of the nation as the leading political actor. The revolutionary atmosphere of

ḥurriyya

had succeeded in overthrowing the supreme authority of the sultan, on the one hand, and the political passivity of the nation, on the other. According to the Ottoman electorate, the members of parliament were their agents, their representatives, with a mission to act on behalf of the nation, to fulfill the hopes and promises of the revolution itself. At the Jerusalem celebration sending off al-Khalidi and al-Husayni, David Yellin, himself a failed candidate for parliament, addressed the crowd (“O Ottoman citizens!”) and new representatives: “O elected ones, you were selected from among the candidates, not only because you promised to bring reform to the province, which others did as well, but of those who are men of thoughts and men of deeds, it is our fortune that you are of the latter. We collectively hope that your love for the homeland and your famous readiness will enable us to gain together…the improvements necessary for our holy land.”

114

Yellin closed his speech with a play on the names of the representatives: “we collectively hope that ‘Ruhi' will revive our spirits. And ‘Sa'id' will make us happy. And ‘Hafiz' will protect our rights. Long live the delegates and long live the homeland and long live the constitution and the basic law!”

This understanding of the role of the deputies to act on behalf of the will of the nation was reiterated by newly elected MP Ruhi al-Khalidi: “We are going to aid the Ottoman nation irrespective of its differences in religions and languages for this is the rule of law and this law belongs to the nation…. Laws and regulations are an expression of the will of the nation [

irādat al-umma

], which is [carried out] by means of its representatives according to the rule of law.” Al-Khalidi went on to explain how the parliament would operate, what the role of the political parties would be, and how the liberals' first mission should be to reform the Basic Law so that the sultan and his reactionary cronies would not be able to dissolve the parliament or harass its work, as they had the first parliament in 1877-78. “Even if [the reactionaries] give an order and tell them ‘Get out, O gentlemen, from this council,' [the liberals] will answer with one voice and a rushing heart: ‘We entered this council by the will of the nation, and we will not leave it except through the force of arms.'”

115