Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (28 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

Subscription rates tell only part of the story, however, as newspapers were often read out loud, passed from hand to hand, or borrowed in coffeehouses, reading rooms, and libraries. According to the Columbia student, for example, each purchased Istanbul newspaper went through five to fifteen readers on average, as the original purchaser would share it with family members, neighbors, and friends before sending it to relatives in the provinces.

20

In Palestine, there is evidence of this newspaper sharing as well as other steps taken in an effort to engage financially modest, nonurban, and nonliterate groups of people. A proposal was recorded in the fall of 1908 to establish regular institutionalized reading nights, where an “educated Arab” would read the newspaper in a central location for the benefit of the masses that could not read. We also have records of bookshops and libraries that either lent or rented out reading materials, including a new “readers’ library” by means of which readers could pay a small fee for access to the latest news, and patrons at cafés could catch up on reading newspapers while sipping their tea or coffee or smoking a

nargileh.

Lastly, the newspaper

Palestine

(

Filas īn

īn

) sent free copies to each village in the region with a population over one hundred.

21

Thus, with a conscious awareness that their readership was both changing and expanding, these newspapers went about shaping the revolutionary Ottoman public sphere. As one contemporary journalist and press observer noted, the Arabic press was uniform in expressing the belief that saw the revolution as “bringing redemption to the Ottoman people in the Ottoman lands, without difference to religion and nationality.”

22

The Arabic press was not alone in this sentiment, for the Judeo-Spanish newspaper

Liberty (El Liberal)

hailed in its opening column, “…this day in which all the people of the empire trill with joy, this day that finally marks the beginning of a new life for all Ottomans.”

23

Many other newspapers in Palestine explicitly emphasized their sympathy with the new political reality, such as

Progress (Al-Taraqqi)

, Equity

(Al-In āf)

āf)

, Success

(Al-Najā ), Liberty (Al-

), Liberty (Al- urriyya), Constitution (Al-Dustūr), Voice of Ottomanism (

urriyya), Constitution (Al-Dustūr), Voice of Ottomanism ( awt al-'Uthmāniyya)

awt al-'Uthmāniyya)

, and

Liberty (Ha- erut

erut

; a Sephardi newspaper, which had a Ladino version,

El Liberal).

24

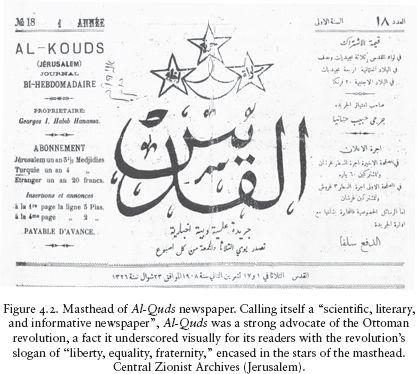

And, as shown in

Figure 4.2

, the masthead of the newspaper

Jerusalem

proudly illustrated its embrace of the revolutionary principles of “liberty, equality, fraternity” in the stars— urriyya, musāwā, ikhā’.

urriyya, musāwā, ikhā’.

In this, the press was simultaneously echoing popular excitement in the aftermath of the revolution and placing itself at the forefront

of the Ottomanist and Ottomanizing program.

25

In order to prepare the citizenry for the new era, the press took it upon itself to serve as a link between the citizenry and the transforming state in two important ways: first, by strengthening Ottomanism and sentiments of belonging to empire; and second, by solidifying imperial citizenship. First, newspapers actively helped shape an imperial identification among their readers, publishing reports on the history of the Osman dynasty, for example, or of the Ottoman liberals from the mid-nineteenth century to the revolution. As well, the press served as an intermediary between the state and the populace, and we have seen that the multilingual press published important new laws; transmitted directives from the central and local governments; informed citizens how to carry out normal business with government offices; and reported on the functioning of the various regional and local councils.

26

In addition to underscoring this vertical relationship between the reader and the Ottoman state, the press simultaneously played an important role in forging horizontal ties between Ottomans. Strengthening

ties across city, region, and empire, the press also served as a bridge between languages, communities, and reading publics. Often through regular columns, the press relayed news from the capital in Istanbul, neighboring provinces and cities in the empire, and events from faraway corners of the Ottoman world.

27

In the Palestinian press, for example, there were regular reports of famine in Anatolia; the Bedouin revolts in Kerak; updates on secret societies in Crete, Albania, the Hawran, and Yemen; the Armenian massacres; and of course the wars in Tripoli and the Balkans. Thanks to this coverage as well as to the modern wire services, the Palestinian press and public were tapped in to the major occurrences around the empire and world, and Palestinians thus were able to envision their future in the empire in “real time” conjunction with the empire’s changing contours.

Informing readers about events and attitudes in other corners of the empire and among their compatriots also had the purpose of psychologically and imaginatively linking Palestinians to the broader Ottoman world.

28

For example the Hebrew newspaper

Liberty (Ha- erut)

erut)

displayed a great deal of sympathy and understanding toward the Bedouin revolt in Syria, arguing that the government was taking away the Bedouins' livelihood (protection money from the pilgrimage caravans), conscripting their sons into the army, and demanding their sedentarization and taxation, all without offering them any benefits in return. The paper also criticized the CUP's treatment of the revolts in the Hawran and Albania, already accusing them of Turkification policies inappropriate to the empire’s heterogeneity.

29