Paris in the Twentieth Century (15 page)

Read Paris in the Twentieth Century Online

Authors: Jules Verne

"You!

But why?"

"For

having brought you into the presence of these wild ideas! I've given you a look

at the Promised Land, my poor child, and—"

"And

you will let me enter, won't you, Uncle?"

"Oh

yes, if you will promise me one thing. "

"Which

is..."

"Only

to stroll through. I don't want you to be plowing this ungrateful soil!

Remember what you are, what you need to do, what I am myself, and this day and

age in which the two of us are living."

Michel

made no reply but pressed his uncle's hand; and the latter was doubtless on the

verge of repeating his tremendous arguments when the doorbell rang. Monsieur

Huguenin went to answer it.

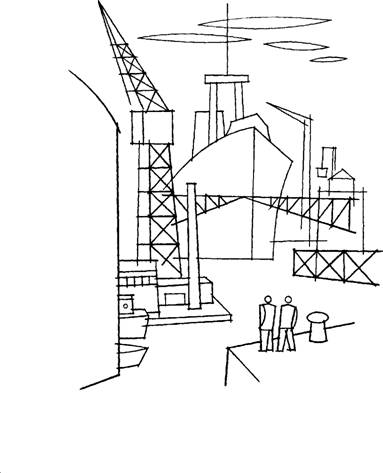

A Stroll to the Port de Grenelle

It

was Monsieur Richelot himself. Michel flung himself into the arms of his old

teacher; a little more and he would have fallen into those Mademoiselle Lucy

held out to Uncle Huguenin, who was fortunately standing at his post and thus

forestalled that charming encounter.

"Michel!"

exclaimed Monsieur Richelot.

"Himself,

" Monsieur Huguenin reassured him.

"Ah!"

exclaimed the professor, "now this is a happy surprise, and an evening

which bodes laetanterly. "

"Dies albo nodanda lapillo,

"

riposted Monsieur Huguenin.

"As

our dear Flaccus says, " Monsieur Richelot confirmed.

"Mademoiselle,

" stammered the young man, greeting the young lady.

"Monsieur,

" replied Lucy, with a curtsy that was not altogether clumsy.

"Candore notabilis albo,"

murmured Michel, to the delight of his professor, who forgave this compliment

in a foreign tongue. Moreover the young man had spoken accurately; Lucy's

entire charm was portrayed in that delicious Ovidian hemistich: remarkable for

the luster of her whiteness! Mademoiselle Lucy was about fifteen and perfectly

lovely, with long, blond curls falling over her shoulders in the fashion of the

day, fresh and nascent, if that term can express about her what was new, pure,

and blossoming; her deep blue eyes sparkling with naive glances, her pert nose

with its tiny, transparent nostrils, her mouth moist with dew, the almost

nonchalant grace of her neck, her cool and supple hands, the elegant outline of

her figure— everything enchanted the young man and left him mute with

admiration. The young lady was a living poem; he sensed rather than saw her;

she touched his heart before delighting his eyes.

This

little ecstasy threatened to last indefinitely; Uncle Huguenin realized as

much, seated his visitors, managing to shield the young woman from the rays

the poet was giving off, and began talking. "My friends, dinner will be

served quite soon; let's chat awhile until it comes. You know, Richelot, it's

been a good month since I've seen you. How are the humanities going?"

"They're

going... away, " the old professor replied. "I have only three

students left in my rhetoric class. It's a turpe

[59]

decadence! Soon they'll be getting rid of us, and with good reason."

"Getting

rid of you!" Michel exclaimed.

"Can

it really have come to that?" asked Uncle Huguenin.

"Really

and truly, " Monsieur Richelot replied. "Rumor has it that the

Literature professorships, by virtue of a decision taken in the General

Assembly of the Stockholders, will be suppressed for the program of 1962.

"

"What

will become of them?" Michel wondered, staring at the girl.

"I

can't believe such a thing, " said his uncle, frowning. "They

wouldn't dare. "

"They

will dare, " Monsieur Richelot replied, "and it will be for the best!

Who cares about Greek and Latin? All they're good for is to provide a few roots

for modern science. The students no longer understand these wonderful

languages, and when I see how stupid these young people are, I don't know which

I feel more intensely, despair or disgust!"

"Can

it be possible, " asked young Dufrénoy, "that your class is reduced

to three students?"

"Three

too many, " grumbled the old professor.

"And

all three of them dunces into the bargain, " said Uncle Huguenin.

"First-class

dunces!" returned Monsieur Richelot. "Would you believe that just the

other day one of them translated

jus divinum

as

'divine juice'?"

"Divine

juice!"

exclaimed

Uncle Huguenin, "that's a budding drunkard you have there. "

"And

yesterday, just yesterday!

Horresco referens—

guess,

if you dare, how another one translated this verse from the fourth canto of the

Georgics: immanis pecoris custos..."

"I'd

say it was...," offered Michel.

"I

blush for it to the tops of my ears, " said Monsieur Richelot.

"All

right, tell us, " replied Uncle Huguenin. "How did he translate that

passage in our year of grace 1961?"

"

'Guardian of a dreadful pecker, ' " replied the old professor, covering

his face.

Uncle

Huguenin could not contain a great burst of laughter; Lucy turned her head

away, with a smile; Michel watched her sadly; Monsieur Richelot didn't know

where to look.

"O

Virgil!" exclaimed Uncle Huguenin, "would you ever have suspected

such a thing?"

"You

see what it is, my friends!" resumed the professor. "Better not to

translate at all than to do it like this. And in a rhetoric class! Best to

eliminate the whole thing!"

"What

will you do then?" asked Michel.

"That,

my boy, is another question, but the moment has not arrived for an answer.

We're here to have a good time—"

"Then

let's have dinner, " interrupted Uncle Huguenin.

During

preparations for the meal, Michel started a deliciously banal conversation with

Mademoiselle Lucy, full of charming nonsense beneath which occasionally

gleamed the traces of thought; at fifteen, Mademoiselle Lucy was entitled to be

much older than Michel at sixteen, but she did not abuse the privilege.

However, apprehensions for the future darkened her pure forehead and solemnized

her expression. She gazed anxiously at her grandfather, who epitomized all of

life to her. Michel intercepted one of these glances.

"You

love Monsieur Richelot a great deal, " he said.

"A

great deal, Monsieur. "

"So

do I, Mademoiselle. " Lucy blushed slightly at seeing her affection and

Michel's meet upon a mutual object; it was virtually a union of her most

intimate feelings with those of another! Michel felt the same, and no longer

dared look at her.

But

Uncle Huguenin interrupted this tete-a-tete with a loud announcement that

dinner was served. A neighborhood caterer had brought in a splendid meal

ordered for the occasion. The guests took their places at the feast.

A

thick soup and an excellent stew of boiled horse meat, a dish much esteemed up

to the eighteenth century and restored to honor by the twentieth, contended

with the diners' initial appetite; then came a leg of lamb prepared with sugar

and saltpeter according to a new method which preserved the meat and added

delicate qualities of flavor, garnished with several tropical vegetables now

acclimatized in France. Uncle Huguenin's good humor and enthusiasm, Lucy's

grace as she served the others, Michel's sentimental frame of mind—all

contributed to making this family repast a charming occasion. However

prolonged, it still ended too soon, and the heart was obliged to yield before

the satisfactions of the stomach.

Everyone

got up from the table.

"Now,

" said Uncle Huguenin, "we must find a worthy ending to this fine

day. "

"Let's

go for a walk!" exclaimed Michel.

"Oh,

let's!" Lucy chimed in.

"Where

shall we go?" asked Monsieur Huguenin.

"To

the Port de Crenelle, " Michel replied.

"Perfect.

Leviathan IV

has

just docked, and we can have a look at this marvel. "

The

little group went out into the street, Michel offered his arm to the young

lady, and everyone headed for the railroad station.

This

famous project of a Paris seaport had at last been realized; for a long while

it had not raised much interest; many visited the canal site and were loud in

their derision, dismissing the entire venture as a folly. But in the last

decade, the incredulous had been obliged to yield to the facts.

Already

the capital seemed likely to become something like a Liverpool in the heart of

France; a long series of canals and wet docks dug in the vast plains of

Grenelle and Issy could accommodate a thousand high-tonnage vessels. In this

herculean task, industry seemed to have achieved the extreme limits of the possible.

Frequently

during previous centuries—under Louis XIV, under Louis Philippe—this notion of

digging a canal from Paris to the sea had been broached. In 1863, a company was

authorized to prepare plans, at its own expense, linking Paris to Creil,

Beauvais, or Dieppe; but the elevations necessitated many locks and

considerable waterways in order to realize such a project; the Oise and the B

é

thune,

the only available rivers in this area, were soon judged inadequate, and the

company abandoned its endeavor.

Sixty-five

years later, the State returned to the notion, favoring a system already

proposed in the last century, a system whose logic and simplicity had caused it

to be summarily dismissed at the time; it involved using the Seine, the

natural artery between Paris and the Atlantic.

In

less than fifteen years, a civil engineer named Montanet cut a canal which,

starting on the Plaine de Grenelle, ended just above Rouen, measuring a hundred

and forty kilometers in length, seventy meters in width, and twenty meters in

depth; this operation produced a bed containing about a hundred and ninety

million cubic meters; such a canal would never be in danger of running dry, for

the fifty thousand liters per second the Seine produces amply sufficed to fill

it. Excavations in the bed of the lower part of the river had opened the canal

to the biggest ships. Thus navigation from Le Havre to Paris no longer raised

any difficulties.

There

existed in France at the time, according to the Dupeyrat Project, a railway

network on the tow- paths of all canals. Powerful locomotives towed the tugs

and transport vessels with no difficulty. This system, greatly enlarged, had

been applied to the Rouen canal, and it may readily be imagined how rapidly commercial

vessels as well as government shipping sailed up to Paris. The new port had

been magnificently constructed, and soon Uncle Huguenin and his guests were

strolling on the granite quays, amid a considerable crowd.

There

were eighteen wet docks, only two of which were reserved for the government

ships assigned to protect the fisheries and the French colonies. Here, as well,

were reproductions of armored frigates of the nineteenth century, which the

archaeologists admired without quite understanding.

These

war machines had ultimately assumed incredible though readily explainable

proportions; for a period of some fifty years, there had been an absurd duel

between armor and cannonballs, as to which would resist and which would

penetrate. Cast-iron hulls became so thick, and cannon so heavy, that ships

ended by sinking under their burden, and this result brought to a close this

noble rivalry just when cannon- balls were about to triumph over armor.

"This

was how they fought back then, " observed Uncle Huguenin, pointing to one

of these iron monsters pacifically moored at the rear of the basin. "Men

shut themselves up in these floating fortresses, and then they had to sink the

others or be sunk themselves. "

"But

individual courage didn't have much to do in such machines, " protested

Michel.

"Courage

was outdated, like the cannons, " Uncle Huguenin commented with a smile.

"Machines fought, not men; hence the impulse to put an end to wars, which

had become ridiculous. I could still conceive of battle, in the days when you

stood man to man, and when you killed your adversary with your own hands—"

"How

bloodthirsty you are, Monsieur Huguenin!" exclaimed Lucy.

"Not

at all, my dear, I'm merely reasonable, insofar as reason has anything to do

with such things; war once had its raison

d’être

,

but since cannons have had a range of eight thousand meters, and a thirty-six-

millimeter cannonball at a hundred meters could pass through thirty-four horses

and sixty-eight men, you'll have to admit that individual courage had become a

luxury. "

"Indeed,

" Michel commented, "machines have killed bravery, and soldiers have

become mechanics. "

During

this archaeological discussion, the four visitors continued their promenade

through the wonders of the commercial docks. Around them rose an entire town of

taverns where sailors ate their meals and smoked their pipes. These brave

fellows felt quite at home in this mercantile port in the very center of the

Plaine

de Grenelle, and they were free to make all the racket they liked. They formed,

moreover, a distinct population, not mingling with the inhabitants of the other

suburbs, and quite unsociable. It was a kind of Havre separated from Paris by

no more than the width of the Seine.

The

commercial waterways were connected by cantilever bridges operated at fixed

hours by means of the Catacomb Company's compressed-air machines. The water

vanished beneath the ships' hulls; most advanced by means of carbonic-acid

vapor; not a three- master, a brig, a schooner, a lugger, a coasting vessel

which was not fitted with its propeller; wind was no longer a source of energy;

it was no longer in use, no longer sought, and old Aeolus, scorned, hid shamefaced

in his bag.

It

is easy to imagine how cutting through the isthmuses of Suez and Panama had

increased long-distance commercial navigation; maritime operations, delivered

from monopolies and from the shackles of ministerial brokers, enormously

increased; ships multiplied in all forms. Certainly it was a magnificent

spectacle, these steamers of all sizes and all nationalities whose flags spread

their thousand colors on the breeze; huge wharves, enormous warehouses

protected the merchandise which was unloaded by means of the most ingenious

machines; some prepared packing materials, others weighed them, some labeled

them, still others stowed them onboard; ships towed by locomotives slid along

the granite walls; bales of cotton and wool, sacks of sugar and coffee, crates

of tea, all the products of the four quarters of the world were heaped up in

towering mountains of commerce; many-colored panels announced the ships

departing for every point on the globe, and all the languages of the earth were

spoken in this Port de Grenelle, the busiest in the world.

The

sight of this vast basin from the heights of Arcueil or Meudon was really

splendid; as far as the eye could see extended a forest of flag-studded masts;

a tide-signal tower stood at the entrance to the port, while at the rear an

electric lighthouse, no longer much used, rose into the sky to a height of 152

meters. This was the highest monument in the world, and its lights could be

seen, forty leagues away, from the towers of Rouen Cathedral. The entire

spectacle deserved to be admired.

"This

is all really splendid, " said Uncle Huguenin.

"Pulchre

[60]

sight," echoed the professor.

"If

we have neither water nor sea wind, " continued Monsieur Huguenin,

"here at least are the ships which water bears and the wind drives!"

But

where the crowd clustered most thickly, so that it became really difficult to

pass through, was on the quays of the largest basin, which could scarcely accommodate

the recently docked gigantic

Leviathan IV;

the last

century's

Great Eastern

[61]

would not have been worthy to be her launch; her home berth was New York, and

the Americans could boast of having defeated the British; the ship had thirty

masts and fifteen chimneys; of her thirty thousand horsepower, twenty thousand

was for the drive wheels and ten thousand for the propeller; railroad tracks

made it possible to circulate swiftly from one end of her decks to the other,

and in the space between the masts could be admired several squares planted

with huge trees, whose shade spread over flowerbeds and lawns; here the elegant

passengers could ride horseback down winding bridle paths; soil spread to a

depth of three meters over the main deck had produced these floating parks.

This ship was a world, and her crossings achieved prodigious results; she came

from New York to Southampton in three days; sixty-one meters wide, her length

may be judged by the following fact: when

Leviathan

IV

docked

prow foremost at the quay, rear-deck passengers still had to walk a quarter of

a league before they reached terra firma.

"Soon,

" Uncle Huguenin said, strolling under the oaks, rowans, and acacias of

the promenade deck, "soon they'll manage to construct that fantastic Dutch

ship whose bowsprit was already at Mauritius when its helm was still in the

harbor of Brest!"

Were

Michel and Lucy admiring this enormous machine like the rest of this astonished

crowd? I cannot say for certain, but they strolled about, speaking in low

voices, or saying nothing at all, and staring into each other's eyes; they

returned to Uncle Huguenin's lodgings without having seen much, or anything,

of the wonders of the Port de Grenelle!