Peak Everything (5 page)

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Where might we find solace in all this gloom? Well, it could be argued that some not-so-good things will also peak this century:

⢠Economic inequality

⢠Environmental destruction

⢠Greenhouse gas emissions

Why economic inequality? The late, great social philosopher Ivan Illich argued in his 1974 book

Energy and Equity

that inequality increases along with the flow of energy through a society. “[O]nly a ceiling on energy use,” he wrote, “can lead to social relations that are characterized by high levels of equity.”

7

Hunters and gatherers, who survived on minimal energy flows, also lived in societies nearly free from economic inequality. While some forager societies were better off than others because they lived in more abundant ecosystems, the members of any given group tended to share equally whatever was available. Theirs was a gift economy â as opposed to the barter, market, and money economies that we are more familiar with. With agriculture and full-time division of labor came higher energy flow rates as well as widening economic disparity between kings, their retainers, and the peasant class. In the 20

th

century, with per capita energy flow rates soaring far above any in history, some humans enjoyed unprecedented material abundance, such that they expected that poverty could be eliminated once and for all if only the political will could be summoned. Indeed, during the middle years of the century progress was seemingly being made along those lines. However, for the century in total, inequality actually increased. The Gini index, invented in 1912 as a measure of economic inequality within societies, has risen substantially within many nations (including the US, Britain, India, and China) in the past three decades, and economic disparity between rich and poor nations has also grown.

8

In the decades just prior to the 20

th

century, the average income in the world's wealthiest country was about ten times more than that in the poorest; now it is over forty-five times more. According to one study released in December, 2006 (“The World Distribution of Household Wealth,”) the richest one percent of people now controls 40 percent of the world's wealth, while the richest two percent control fully half.

9

If this correlation between energy flow rates and inequality holds, it seems likely that, as available energy decreases during the 21

st

century, we are likely to see a reversion to lower levels of inequality. This is not to say that by century's end we will all be living in an egalitarian socialist paradise, merely that the levels of inequality we see today will have become unsupportable.

Energy and Equity

that inequality increases along with the flow of energy through a society. “[O]nly a ceiling on energy use,” he wrote, “can lead to social relations that are characterized by high levels of equity.”

7

Hunters and gatherers, who survived on minimal energy flows, also lived in societies nearly free from economic inequality. While some forager societies were better off than others because they lived in more abundant ecosystems, the members of any given group tended to share equally whatever was available. Theirs was a gift economy â as opposed to the barter, market, and money economies that we are more familiar with. With agriculture and full-time division of labor came higher energy flow rates as well as widening economic disparity between kings, their retainers, and the peasant class. In the 20

th

century, with per capita energy flow rates soaring far above any in history, some humans enjoyed unprecedented material abundance, such that they expected that poverty could be eliminated once and for all if only the political will could be summoned. Indeed, during the middle years of the century progress was seemingly being made along those lines. However, for the century in total, inequality actually increased. The Gini index, invented in 1912 as a measure of economic inequality within societies, has risen substantially within many nations (including the US, Britain, India, and China) in the past three decades, and economic disparity between rich and poor nations has also grown.

8

In the decades just prior to the 20

th

century, the average income in the world's wealthiest country was about ten times more than that in the poorest; now it is over forty-five times more. According to one study released in December, 2006 (“The World Distribution of Household Wealth,”) the richest one percent of people now controls 40 percent of the world's wealth, while the richest two percent control fully half.

9

If this correlation between energy flow rates and inequality holds, it seems likely that, as available energy decreases during the 21

st

century, we are likely to see a reversion to lower levels of inequality. This is not to say that by century's end we will all be living in an egalitarian socialist paradise, merely that the levels of inequality we see today will have become unsupportable.

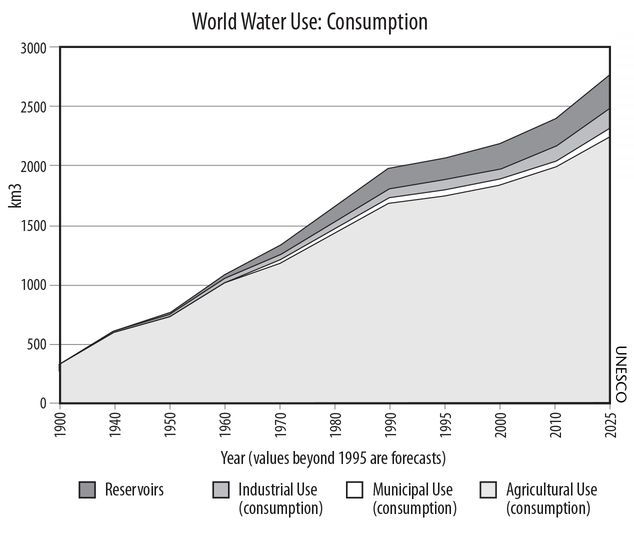

Figure 7. World water use, consumption.

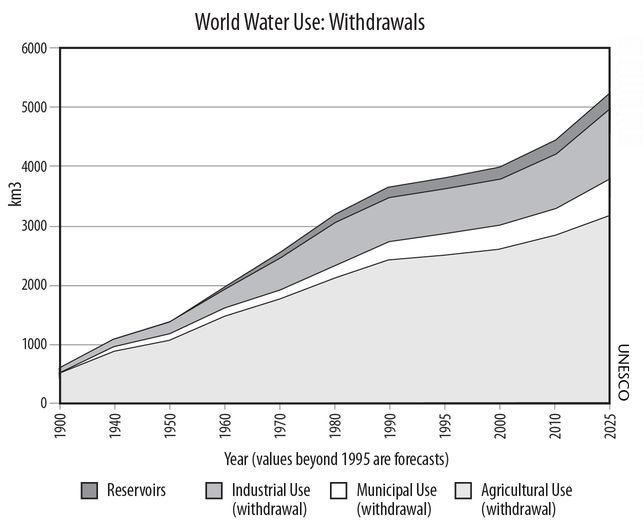

Figure 8. World water use, withdrawals.

Figure 9. Water availability, history, and forecast.

Figure 10. Annual world grain production, total amounts and amounts per capita.

Figure 11. World population, history and forecast.

Figure 12. Annual marine (saltwater) fish catch.

Figure 13. Combined oil, gas, and coal production projections, in billions of barrels of oil equivalent per year. This graph shows the probable future for fossils fuels, the source of roughly 85 percent of the world's current energy budget.

Figure 14. Global arable land.

Similarly, it seems likely that levels of humanly generated environmental destruction will peak and begin to recede in decades to come. As available energy declines, our ability to alter the environment will do so as well. However, if we make no deliberate attempt to control our impact on the biosphere, the peak will be a very high one and we will do an immense amount of damage along the way. On the other hand, we could expend deliberate and intelligent effort to reduce environmental impacts, in which case the peak will be at a lower level. Especially in the former case, this peak is likely to lag behind the others discussed, because many environmental harms involve reinforcing feedback loops as well as delayed and cumulative impacts that will continue to reverberate for decades after human population and consumption levels start to diminish. As the primary example of this, annual greenhouse gas emissions will undoubtedly peak in this century â whether as a result of voluntary reductions in fossil fuel consumption, or depletion of the resource base, or societal collapse. However, the global climate may not stabilize until many decades thereafter, until various reinforcing feedback loops that have been set in motion (such as the melting of the north polar icecap, which would expose dark water that would in turn absorb more heat, thus exacerbating the warming effect; and the melting of tundra and permafrost, releasing stored methane that would likewise greatly exacerbate warming) play themselves out. Indeed, the climate may not return to a phase of relative equilibrium for centuries.

Well, if the goal of the last few paragraphs was to balance bad-news peaks with cheerier ones, that effort so far seems less than entirely successful. Surely we can do better. Are there some

good

things that are

not

at or near their historic peaks? I can think of a few:

good

things that are

not

at or near their historic peaks? I can think of a few:

⢠Community

⢠Personal autonomy

⢠Satisfaction from honest work well done

⢠Intergenerational solidarity

⢠Cooperation

⢠Leisure time

⢠Happiness

⢠Ingenuity

⢠Artistry

⢠Beauty of the built environment

Of course, some of these items are hard to quantify. But a few can indeed be measured, and efforts to do so often yield surprising results. Let's consider two that have been subjects of quantitative study.

Leisure time is perhaps the element on this list that lends itself most readily to measurement. The most leisurely societies were without doubt those of hunter-gatherers, who worked about 1,000 hours per year, though these societies seldom if ever thought of dividing “work time” from “leisure time,” since all activities were considered pleasurable in their way.

10

For US employees, hours worked peaked in the early industrial period, around 1850, at about 3,500 hours per year.

11

This was up from 1,620 hours worked annually by the typical medieval peasant. However, the two situations are not directly comparable: a typical medieval workday stretched from dawn to dusk (16 hours in summer, 8 in winter), but work was intermittent, with breaks for breakfast, midmorning refreshment, lunch, a customary afternoon nap, mid-afternoon refreshment, and dinner; moreover, there were dozens of holidays and festivals scattered throughout the year. Today the average US worker spends about 2,000 hours on the job each year, a figure somewhat higher than it was a couple of decades ago (in 1985 it was closer to 1,850 hours). Nevertheless, an historical overview suggests that the time-intensiveness of human labor seems to peak in the early phase of industrialization, and that a simplification of the modern economy could result in a reversion to older, pre-industrial norms.

10

For US employees, hours worked peaked in the early industrial period, around 1850, at about 3,500 hours per year.

11

This was up from 1,620 hours worked annually by the typical medieval peasant. However, the two situations are not directly comparable: a typical medieval workday stretched from dawn to dusk (16 hours in summer, 8 in winter), but work was intermittent, with breaks for breakfast, midmorning refreshment, lunch, a customary afternoon nap, mid-afternoon refreshment, and dinner; moreover, there were dozens of holidays and festivals scattered throughout the year. Today the average US worker spends about 2,000 hours on the job each year, a figure somewhat higher than it was a couple of decades ago (in 1985 it was closer to 1,850 hours). Nevertheless, an historical overview suggests that the time-intensiveness of human labor seems to peak in the early phase of industrialization, and that a simplification of the modern economy could result in a reversion to older, pre-industrial norms.

Other books

Experiment in Terror 07 Come Alive by Karina Halle

The Eagle's Throne by Carlos Fuentes

The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) by Guerber, H. A.

Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight by Linda Bacon

Find Big Fat Fanny Fast by Joe Bruno, Cecelia Maruffi Mogilansky, Sherry Granader

The Grown Ups by Robin Antalek

The Surrender of Miss Fairbourne by Madeline Hunter

Switch - a full length bdsm erotic novel by Clique, Clarice

Flame of Cytherea: Cytherean Chronicles book 1 by D. R. Rosier

Cuentos completos by Isaac Asimov