Raising Hell (25 page)

And although their methods and the interpretation of their data varied over the centuries, the chiromancers (or palmists, as they were often called) did gradually build up a kind of catalog of hand shapes and traits and features which they could use for handy reference. The first question that had to be decided upon, however, was which hand to read. Many palmists insisted on using the left hand, as that was the hand (most people being right-handed) that had suffered less wear and tear; the lines and signs in it, they felt, would be more visible and undisturbed. (Of course, in a left-handed person, the right would be used, for the same reasons.) Some readers looked at both hands, and many distinguished between the two by saying that, in a right-handed person, the left hand displayed the inherited characteristics, while the right showed what had, and would be, accomplished in the person’s life. (Again, this distinction was reversed for lefties.)

As for the shape of the hand, there were several broad categories into which it could fall. First of all, there was the question of length; palmists measured the length of the hand from the top of the extended middle finger to the bulge of the wristbone (known to the medical profession as the ulnar styloid) on the outside of the forearm. If this distance seemed unusually long, the person was thought to be of a pensive and brooding nature, inclined to spend more time working toward perfection than toward getting the job over and done with. If the length was unusually short, the person was thought to be imaginative and creative but a tad impractical. If the hand and fingers were thin,

it implied a nervous disposition and possibly a timid one; if they were thick, it suggested a more carnal and earthy nature.

The influential French chiromancer Henri Rem declared that hands could be divided up into four major types, with a host of emotional attributes corresponding to each one. The first type he called the pointed hand, with sharp, tapered fingers. “Pointed fingers,” he wrote, “offer a conduit free and without obstacle, and in this resemble the magnetised points of lightning conductors; they easily draw in and emit fluid, consequently absorb spontaneously surrounding ideas and emit them in the same manner. Hence the inspirations, the illuminations, the inventions which flow from pointed fingers and make dreamers, poets and inventors.” Among the notables with pointed fingers, Rem included Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe, George Sand, and the painters Raphael and Correggio. He also observed that the pointed hand belonged to those with a taste for luxury and sensual pursuit. What it wasn’t well suited for was “the battle of life, for reasoning, for materiality, for effort.”

The second type of hand Rem identified was the square hand, whose fingers ended in a clear, squarely cut nail. This, Rem declared, was “the hand of reason, of duty and of command.” It belonged to those with a cool and methodical nature, who could consider a problem dispassionately and come up with a logical, precise solution to it. Square-handed people of note were Voltaire, Rodin, Holbein, and the great stage actress Sarah Bernhardt. There were, however, a couple of worrisome things to look out for: If the middle finger was too square at the end, then it implied an uncompromising, and even intolerant, disposition. Even worse, “if by an excess of malformation, the square finger attains the shape of a ball, a tendency to murder may be feared.”

The third type of hand, the conical, was “the philosophical hand,

par excellence.

" Why? Because, with its gently rounded fingertips, it was partly square and partly pointed—an ideal mix of attributes. “It is the hand of him who can understand everything and love everything, who can acknowledge his errors, be

benevolent, friendly, indulgent, the friend of peace and harmony, of order and comfort.” Rousseau had the conical hand, as did Molière, La Fontaine, and the legendary Italian actress Eleonora Duse.

Finally, there was what Rem called the spatulate hand, with “spatula shaped fingers, with the nail joint almost flat (exception must be made in the case of deformation owing to the use of tools).” Spatulate fingers could be found on people who looked before leaping, who were sometimes overly confident and overbearing. Such people had an inborn aversion to bureaucrats and hated any form of confinement, whether it was as extreme as a prison or as ordinary as a workplace. “It is the hand of instinct,” Rem wrote, “of feelings but little restrained, of the material mind, of revolt (most revolutionaries have these finger signs).” Among the spatulates were Rembrandt, Rubens, and Napoleon III, the emperor of France from 1852 to 1870.

Even Rem conceded, however, that few hands were purely one type or the other; most displayed certain features of different types, and so they required a practiced eye to assess their true meaning—all, perhaps, but the “elementary hand,” which Rem said he often came across in the country. “The fingers are thick, massive, it is the hand of the peasant, instinctive, of the rudimentary being. . . . It is the helpless hand of the born slave.”

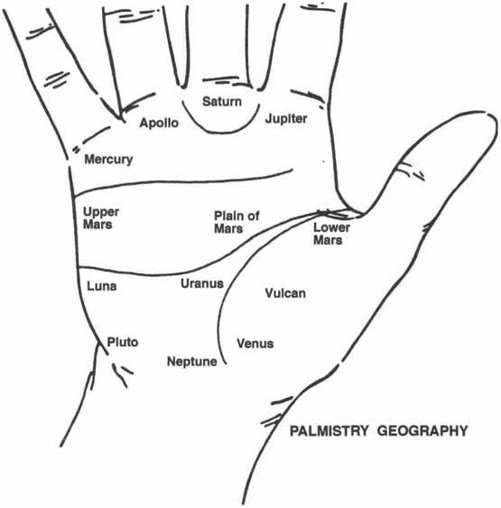

But even more telling than the size or shape of the hand were the signs to be read in its palm—the lines (or creases), the mounts (or hills), and the valleys (or plains). In nearly every form of palmistry, this information is correlated to astrological and mythological lore. To get a rough idea of where these various features lie and what they are supposed to reveal of the future, imagine a left hand, with its palm facing you. We’ll start by laying out the mounts, or fleshy elevations, of the palm. Their size, their position in respect to the adjacent mounts, the ways in which they are transected by the lines of the palm, all of these factors are thought to influence their power and significance, but overall the mounts and their respective meanings go pretty much as follows.

The first mount is the raised area of the palm that sits at

the base of the thumb. This is called the Mount of Venus, after the goddess of love and beauty. It represents warmth, affection, and sexual allure. On the negative side, however, it can betoken an indiscreet and tasteless nature, given to promiscuity and irresponsible behavior.

Moving just above that, to the crux of the thumb and index finger, is the mount called Inner (or Lower) Mars, named after the god of war and power. Not surprisingly, it suggests energy and daring, adventure and bravery. But it also suggests wanton destruction and malice.

Next, at the base of the index finger, is the Mount of Jupiter, after the king of the Greek gods, and it symbolizes justice, pride, and ambition. On the downside, it can convey pomposity, arrogance, and tyranny.

At the base of the middle and longest finger is Saturn—authoritarian, rigorous, controlling, and sometimes a bit dull. But good at amassing and maintaining a fortune.

The Mount of Apollo lies below the fourth finger. Like the sun god after which it is named, it suggests creativity, beauty, and charm. But it can also signal fickleness, conceit, and an unwise proclivity to gamble.

Just below the little finger is the Mount of Mercury, standing, like the messenger of the gods, for quick-wittedness and adroit maneuvering. But at the same time, it can suggest dishonesty, greed, and compulsive chattiness.

Moving just below Mercury, and running along the outside of the hand, is the mount called Outer (or Upper) Mars, representing such laudable qualities as courage and consideration, and such negative traits as irrationality and stubbornness.

Finally, there’s the Mount of Luna, which sits at the base of the palm, on the side opposite the thumb. Luna signifies imagination and introspection, vitality, and a love of travel. Less favorably, it can suggest a selfish, secretive, and overly sensitive nature.

The central area of the palm that is bordered on all sides by one or more of the various mounts is called the Plain of Mars. If it’s full and fleshy, it indicates an energetic and hopeful spirit.

If it’s visibly depressed, or hollowed out, it conveys ineffectuality and pessimism. If it falls somewhere between these two extremes, if it’s got a gentle curve to it, then that suggests a well-balanced, good-natured temperament.

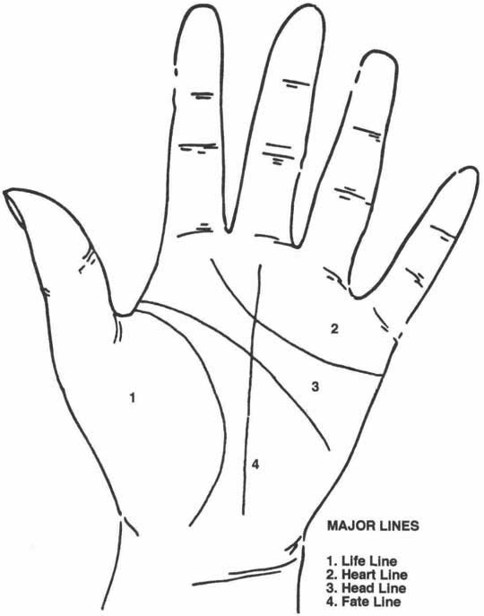

But the feature that has always drawn the most attention from palmists and their clients is the lines that furrow the palm. Are these lines deep and long or short and shallow? Are they complete, or do they instead stop and start? Are they many in number, or are they few? According to one theory, people with more sensitive and complicated souls have an abundance of lines, while those of a simpler, less intelligent nature have not nearly as many. Again, the interpretation of the lines is largely up to the individual palmist. But even so, some general observations can be made.

Five lines are considered by most palm readers to be the most significant. The first of these is the Line of Life, which runs around the base of the ball of the thumb. If this line is deep, it signifies great energy and drive; if it’s not, it suggests lassitude. If there are parallel lines running beside it, this indicates a strong need for affection and the company of other people. If it makes a wide curve toward the center of the palm, it suggests an active nature; if it curves close to the thumb, it shows an activity of the mind, instead.

The Head Line begins above the Life Line, in the Upper Mars area, then curves outward, across the Plain of Mars, and toward the opposite edge of the palm. If this line is deep, then the person’s thoughts will be equally deep; if it’s shallow, it indicates a more pragmatic than inspired nature. If it’s not there at all, there will be death by accident. If it is wavy, the person’s thoughts will go in many different directions; if it’s straight, it suggests practicality.

The Heart Line starts at the outer edge of the palm (known as the percussion) and travels across toward the Mount of Jupiter, below the index finger. As would be expected, it represents the more tender emotions, and for that reason was traditionally supposed to be more evident and significant in the palms of women than in those of men. A Heart Line that suggests a favorable

love life, one filled with affection and conjugal joy, will be straight and unbroken and carry a healthy hue. If it’s too reddish, it might signal such passions as jealousy or over-possessiveness, and if it’s too pale, it might signal a dearth of amorous activity. (Never a happy sign to see in one’s own palm.)

Palmistry Geography. Edward D. Campbell,

The Encyclopedia of Palmistry,

New York: A Perigee Book, 1996. Courtesy of Irving Perkins Associates.

**

The Line of Fate (also called the Line of Luck or Destiny) runs in a roughly vertical course, starting at the wrist and moving up the palm toward the Mount of Saturn at the base of the middle finger. If it actually lands at Saturn, then that signifies a happy and contented old age. But the line may veer off toward one of the other mounts or lines, and depending on where it goes, many other things may be indicated: if, for instance, it stops short, at the Head Line, it may indicate psychological difficulties or unwise and impulsive behavior; if it ends at the Heart

Line, it may signal heart trouble or a change in position as a result of a romantic liaison; if it forks, the golden years may not be so golden, after all. If it’s very red in color, then watch out for sudden disasters.

Major Lines. Edward D. Campbell,

The Encyclopedia of Palmistry.

New York: A Perigee Book, 1996. Courtesy of Irving Perkins Associates.

**

Finally, of the five major lines, there’s the Line of Apollo (or, simply, the Sun). This one can start at several different places in the hand, though most commonly it begins at the ring around the wrist and heads toward the root of the ring finger (the Mount

of Apollo). Sometimes it will even bifurcate this mount with a fairly deep groove. When it does, it’s an indication of the person’s enthusiastic and outgoing nature, and it reveals a lot of luck and even, possibly, great fame to come. In the view of many palmists, if the line is altogether missing, then you might as well hang it up—success just isn’t in the cards (or palm) for you.

Besides the lines and mounts, however, there are a host of other signs that can be read in the palm, and these either add to or subtly ameliorate the more pronounced features. There’s the Ring of Solomon, for example, which makes a short loop from the base of the index finger around to the other side of the middle finger. Named after King Solomon, renowned for his skill in magic, this line shows a talent for the occult and a strong ability to sway other people to do your own will.