Raising Hell (23 page)

Alectromancy,

a variant of the gyromancy described above, required a barnyard cock. And it could only be performed when the sun or moon was in Aries or Leo.

Once again, a circle was drawn on the ground, and its border was marked with the twenty-six letters of the alphabet; a kernel of wheat was placed on each letter. A young white cock, which had been declawed, was then forced to swallow a tiny parchment scroll on which magical words had been written. Holding the cock aloft, the magician recited an incantation before depositing the bird inside the circle. From that point on, it was important to keep track of which grains the bird pecked, and in what order. As soon as the bird ate a grain, it was replaced (just in case the word being spelled out used that letter more than once).

According to one ancient account, Iamblichus, a Syrian philosopher who also dabbled in magic, decided to see if this method would help him find out who should succeed Valens Caesar as ruler of the empire. But the bird only pecked at four letters—THEO—and there were four contenders whose names began with those letters: Theodosius, Theodotus, Theodorus, and Theodectes. The magician was left wondering who the successor would be. But the emperor Caesar himself, hearing about the prophecy, decided to take matters into his own hands and had several of the possible choices executed. Iamblichus, figuring his own number was up, too, swallowed poison.

Birds were one of the earliest and most popular elements of augury. As early as the first millennium

B.C.,

the Etruscans had studied the behavior of birds as well as their entrails and then organized what they had learned into an elaborate code of religious ceremonies known as the

disciplina Etrusca.

The Romans were no slouches at it, either. In fact, they had a state-sanctioned college of augurs (soothsayers), drawn from men of highest merit and awarded their positions for life. Recognizable by their distinctive togas (

trabeas

) with scarlet stripes and purple hems, it was the job of the augurs to categorize and interpret the behavior of birds, along with all other kinds of omens, and pass along that information to the appropriate public officials.

All in all, there were two kinds of omens. First, there were the commonplace and occasional omens, domestic events such as spilled salt, a leak in the roof, wine turned to vinegar, which the augurs eventually stopped bothering with; there were just too many of these omens, they were piling up too fast to record, and in the long run they were proving to be of too little importance.

Instead, the Roman augurs concentrated on larger natural phenomena—thunder, lightning, falling stars—and how these might be interpreted to convey the will of the gods. To get an accurate reading, the augur set up a tent on the eve of taking the omens, slept in it, and then, the next morning, rose early. There was only one opening in the tent, and it had to face south. That put the lucky quarter, the east, on his left; by and large, signs on that side were considered favorable, while signs on the right, or west, side were considered unfavorable. (In Greece, however, the situation was reversed: the seer faced north, and signs on his right side were the good ones.) Sitting on a stone or on a chair so solid it would never creak (creaking chairs could be considered omens in themselves), he uttered a prayer to the gods and then stared out at the space before him.

If, however, he was planning to concentrate his efforts on the flight and behavior of wild birds, he might situate himself on top of a tower or at the crest of a hill and face eastward.

Using his

lituus

(a staff free from knots, with a curved handle), he marked out his

templum

(the consecrated section of the sky he would use for his observations), drew a cowl over his head, and made a propitiary sacrifice to the gods. Then he was ready to go.

The first thing he had to do was know his birds—they weren’t all of equal value. Some, such as the eagle, buzzard, and vulture, were significant because of the speed or direction in which they flew; others, such as the owl, crow, and raven, were chiefly noted for their cry—which was generally considered an ominous sign. The woodpecker and the osprey counted on both scores.

Overall, if birds flew toward the east, the direction of the sunrise, the news to come would be good; if they flew westward, where the afterworld was thought to be located, the news would not be so welcome. If they kept low to the ground and skittered about in confusion, then they were agitated and upset—not a happy portent of things to come.

Their songs, too, were full of meaning. Were their voices strong and vibrant? Or weak and quavering? It was a good sign if an augur heard a crow cry to his left or a raven to his right. And it was favorable, too, if a bird was seen flying with food in its beak or eating voraciously. If, for instance, the sacred chickens, which were kept in cages and often consulted by Roman generals, ate so quickly that bits of food dropped from their beaks, this was considered a very good omen. (In his work

On Divination,

however, Cicero claimed it was a put-up job—that the chickens were starved in advance so that their gluttony could always be seen as a sign of Jupiter’s goodwill.) Adding up all the data and weighing it was a difficult task, which the augurs tried to make easier for themselves by keeping detailed archives, the

commentarii augurum,

and later distilling that information into a handy manual for regular (but not public) use, called the

libri augurum.

Birds were not the only animals used for divination in the ancient world and on into the Middle Ages. In a practice sometimes

known as

zoomancy,

good and bad omens were drawn from the sight and the sound, the comings and the goings, of everything from butterflies to bunny rabbits.

If a swarm of bumblebees alighted in your garden, that was a portent of prosperity. If their humming was low and steady, that was a good sign. If, however, their buzzing became louder and more agitated, it wasn’t. (Not exactly a shock.) The sound of a wasp suggested malicious gossip or an unexpected visit from someone you’d never met. Small spiders brought money to the house; big ones, sacred to Athena, were models of industry and must never be squished. A spider spinning its web in your house, however, could be a sign that someone was plotting against you.

Black cats spelled bad luck, as many people believe even today, especially if they crossed your path or stole in front of a funeral procession. White ones could bring good luck. If the cat was busy rubbing its paw behind its ear, it was time to close the windows—rain was coming.

A dog howling in the dark was a warning that ghosts were lurking about and death was imminent. For the longest time, dogs were thought capable of scenting death for miles around. But in the folklore of the northern European countries, the appearance of a spotted dog was a happy sign; three white dogs was an even happier omen.

Traditionally, the glimpse of a lizard was bad news—signifying that a miscarriage would occur—while a frog was good news; frogs were emblematic of lifelong passion.

Weasels were a sign of trouble at home.

If you happened to spot a piebald pony, it was good luck, and if you thought fast enough, you could make a wish upon it; if, however, you looked at the horse again, the wish would no longer come true. Donkeys rolling around in the dust were a sign of good weather. Cattle who stopped grazing and lay down in the field were harbingers of inclement weather; when they got up and started running around, a storm was soon to ensue.

A hare seen darting about a graveyard was considered a shade of the dead; a snake slithering among the headstones was

a symbol of fertility, until it disappeared into the ground—when it became a bearer of messengers to the afterworld.

If rats were spotted deserting a ship while it was still at anchor in the harbor, that was bad news for the next voyage (and many a sailor would fail to report for duty). When rats deserted a sinking ship, it wasn’t so much an omen as it was common sense.

When, according to one ancient story, a Gothic king named Theodotus wanted to know the outcome of an impending battle with the Romans, he asked a Jewish soothsayer what to do. The seer told him to take thirty hogs, give some of them Roman names and some of them the names of Goths, and then divide them into separate pens. When the pens were opened at the appointed time, all of the Roman hogs were alive, but half of them had lost their bristles. The Gothic hogs, however, were all lying dead. The king hardly needed to be told what this meant: his own soldiers would be slain to the very last man, but the Romans would lose only half of their own army.

The use of a wand, staff, or divining rod to discover everything from water sources to buried treasures is one of the oldest and most practiced of the divinatory arts, and is known, in its many variations, as

rhabdomancy.

Moses, who was schooled in all the magical arts of Egypt, invariably used his staff in performing his wonders, whether it was striking the rock with his staff to make water gush forth or, even more notably, parting the vast expanse of the Red Sea so that the Israelites might cross with safety.

In almost every form of magic, a wand or rod is used, in which the magician’s powers are both literally invested and symbolically represented. But over time, rhabdomancy came to refer almost exclusively to the use of the divining rod; by the sixteenth century, especially in the Harz mountain region of Germany, the forked stick had become accepted as a mining tool no more unusual than a pick or shovel.

There were several different ways to make and use a divining

rod. In a treatise on the subject published in Paris in 1725, the abbé de Vallemont offered the most common method:

A forked branch of hazel, or filbert, must be taken, a foot and a half long, as thick as a finger, and not more than a year old, as far as may be [determined]. The two limbs (A and B) of the fork are held in the two hands, without gripping too tight, the back of the hand being toward the ground. The point (C) goes foremost, and the rod lies horizontally. Then the diviner walks gently over the places where it is believed there is water, minerals, or hidden money. He must not tread roughly, or he will disperse the cloud of vapours and exhalations which rise from the spot where these things are and which impregnate the rod and cause it to slant.

The exact physics of all this—how these “vapours” rise up and take control of the end of the rod—are unclear, but the abbé insisted that

the corpuscles—as well those which transpire from the hands of the man into the rod, as those which rise in vapour above springs of water, in exhalations above minerals, or in columns of corpuscles from the insensible transpiration over the footsteps of fugitive criminals—are the immediate effective cause of the movement and bending of the divining-rod.

In a celebrated case from 1692, a divining rod was used to pursue the murderers of a wine merchant and his wife. Their bodies had been found, throats cut by a billhook, in the cellar of their shop in Lyons. When the local constabulary could come up with no leads, they called in Jacques Aymar, a humble peasant renowned for his skills with the divining rod. Aymar had discovered springs of fresh water, underground mines rich with

ore, secret caches of buried treasure; now they asked him if he could track down a murderer. Aymar murmured that he would try.

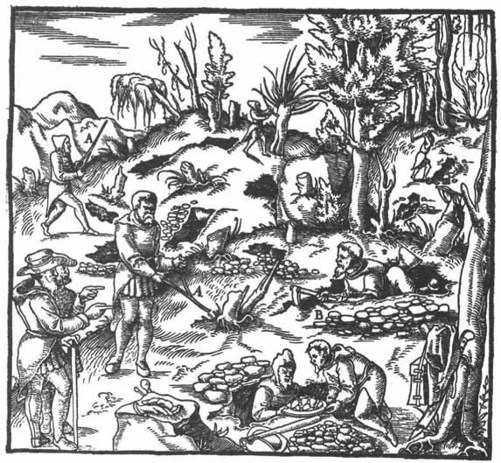

Exploration of a Mining Area by Means of the Divining-rod in the Sixteenth Century. Georg Agricola,

De Re metallica

(Basel, 1571).

**

According to Pierre Garnier, a local physician who wrote an account of the case, the moment Aymar arrived at the scene of the crime, “his rod twisted rapidly at the two spots in the cellar where the two corpses had been found.” Aymar himself, feeling feverish, left the shop and, armed with his rod, “followed the streets where the murderers had passed, entered the courtyard of the archiepiscopal palace, left the town by the Rhone bridge, and turned to the right along the river. He came into a house where he pointed out a table and three bottles as having been touched by the murderers, and it was certified that this was so by two children who had seen them slink into that house.”

From there, the trail led Aymar down to the Rhone again,

where he boarded a boat and followed the murderers down the river. He got off at every port where they had gotten off, found the streets they’d walked, the beds they’d slept in, the tables where they’d eaten. At Beaucaire, he said the murderers had gone their separate ways; he followed in the tracks of the one that the rod seemed most affected by. It led him to a prison, where he looked around at the inmates, then singled out a hunchback who, as it turned out, had just been arrested for a petty theft. At first, the hunchback denied any knowledge of the murders in Lyons, but after repeated questioning, he admitted that he’d been there and witnessed the crime being committed by two other men. Aymar set out again, but after arriving at Toulon and the sea, he stopped short; the murderers, he announced, had already sailed abroad. And though justice remained unserved, Aymar’s tracking was often cited as a persuasive example of the power of the divining rod.