Raising Hell (10 page)

Among other things, he was credited with having invented, while at Oxford, two magical mirrors. One of them could be used day or night to light candles. The other was far more astonishing—it could reveal what someone else was doing, anywhere in the world, at that precise moment. Legend has it that two young noblemen asked to see their fathers in the mirror, and when they did, they saw them with drawn swords, fighting a deadly duel with each other. The two sons instantly drew their

own swords and engaged in a fatal duel of their own—much to Friar Bacon’s dismay.

Bacon was also a great patriot, and he dreamed of one day defending the entire English coastline with an insurmountable wall of brass. But as present engineering techniques did not allow for anything so monumental (for that matter, neither do today’s), he decided to start small, and build a talking brass head that would tell him how to do it. (Strangely enough, these talking brass heads were considered nothing very extraordinary to construct; Robert Grosseteste, bishop of Lincoln, was said to have made one, Albertus Magnus another, and even the ancient Roman philosopher Boethius reportedly had one on hand.) Bacon built his according to all the specifications, but for some reason it wouldn’t talk.

Much frustrated, Bacon and his trusted assistant, Friar Bungay, went to the woods one night and raised a demon to ask it what the problem might be. After demurring at first, the demon finally told them what to do and said the head would talk in one month’s time, though he couldn’t say at exactly what day or hour. He warned the friars that if they didn’t hear it before it had finished speaking, all would be lost.

Consequently, the two friars went on a round-the-clock vigil. But after several weeks of constant attendance on the head, they decided to get some rest one night and delegated the responsibility to Miles, their servant.

And of course, that night turned out to be the fateful one. The head opened its brass jaws and said two words, “Time is,” but Miles didn’t think this was important enough to wake his masters for.

Some time later, it said, “Time was,” but again Miles figured this was pretty inconsequential stuff; in fact, since the head had so little to say, Miles started to jeer at it and sing bawdy songs.

Half an hour more passed, and the head, unhinging its jaws one last time, said, “Time is past,” and exploded into a thousand pieces. Bacon and Bungay, awakened by the deafening roar, raced into the room, but too late to learn anything from the smoldering ruins.

On a separate occasion, however, Bacon did come to the aid of his country (or so legend has it). Using one of his burning glasses, the English army was able to set fire to a French town they were besieging. The French garrison surrendered, a treaty was signed, and a grand fête was held to celebrate the generous terms of the newfound peace.

As part of the festivities, a magical contest was held, with Bacon pitting his skills against a renowned German sorcerer named Vandermast. Vandermast led off by conjuring the spirit of Pompey, in full martial dress, ready to fight the battle of Pharsalia. Bacon, not impressed, summoned the spirit of Caesar, who engaged and, once again, defeated Pompey. The English king was pleased with his friar’s work.

But Vandermast said he was ready for another round. Bacon said he’d let Friar Bungay handle this one. Bungay waved his wand in the air, uttered some incantations, and made the tree of the Hesperides appear before the celebrants, adorned with its golden apples, protected by its watchful dragon. Vandermast took one look and knew just what to do: he summoned up the shade of Hercules, who had slain the dragon and plucked the fruit. The famous warrior was ready to enact his victory all over again when Bacon stepped in to save the day; he waved his wand and Hercules stopped dead in his tracks.

Vandermast, furious, shouted at Hercules to carry on. But Hercules, trembling, said he couldn’t do that—not with a superior power like Bacon’s telling him not to.

Vandermast cursed the ancient shade, and Bacon laughed. Then, to seal the victory, Bacon said that since the spirit wouldn’t be following Vandermast’s instructions, it might as well follow his: he commanded Hercules to carry Vandermast home to Germany, which the spirit obligingly did, throwing the rival magician over his shoulder like a sack of potatoes. When the crowd cried out, sorry to lose one of the competitors so completely, Bacon relented, and said Vandermast would just be in Germany long enough to say hello to his wife, and then he’d be back at the celebration.

This contented the crowd—but not Vandermast. Angry and

humiliated, he later paid a Walloon soldier one hundred crowns to travel to England and kill the friar. But Bacon, who’d consulted his books of magic, knew that the assassin was coming and was ready for him when he sprang out with his sword drawn. Bacon knew that the man was an infidel, one for whom the fires of Hell were just a story. So Bacon, to convince him otherwise, conjured up on the spot the shade of Julian the Apostate; his body besmirched with gore, his skin crackling with flame, the ghost confessed that this was the torment that it had to endure for its apostasy. The Walloon fell to his knees in terror and instantly became a convert to Christianity. In fact, he went on to join the Crusades, where he died fighting for the return of the Holy Lands.

Despite Bacon’s protestations of his own faith, he was commonly thought to have come by his magical powers by making a deal with the Devil. How else, people reasoned, could he perform all these feats? But even there, Bacon’s genius was thought to have prevailed. In return for his skills, Bacon was said to have promised the Devil his eternal soul, on but one condition—that he died neither in nor out of a church. The Devil, thinking this was a pretty safe bet, agreed. And Bacon, during the last two years of his life, built and lived inside of a tiny cell in the outer wall of a church—neither in the church nor out of it.

There, he spent all his time, praying, meditating, having his meals delivered to him, talking to his visitors through a small window. When he died, his bones were interred in the grave he’d dug, inside the cell, with his own fingernails.

THE BELL OF GIRARDIUS

For those of a more squeamish disposition, who wished to avoid digging up coffins or cracking open tombs, there was a more delicate method of summoning the dead, and this was a magic handbell invented by the necromancer Girardius.

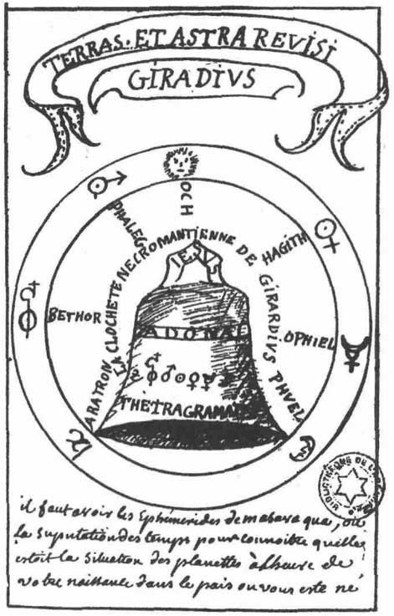

In a document dated 1730, and now housed in the Bibliothéque de l’Arsenal in Paris, the bell is described and diagrammed

and its usage explained. Surprisingly, all of this is done in relatively clear and concise French (most such tracts were written in Latin, of purposeful obscurity). If the document is to be believed, the bell can summon the spirits of the dear departed with the same efficacy as a dinner bell brings family members to the kitchen table.

But first, as with any occult exercise, many careful steps had to be taken. The bell itself had to be cast of an alloy of lead, tin, iron, copper, gold, silver, and fixed mercury. These various metals must be melded “at the day and hour of the birth of the person who desires to be in confluence and harmony with the mysterious bell.” Near the top of the bell, the necromancer must engrave the date of his birth and the names of the seven planetary spirits needed to make the incantation work; in order, these spirits were Aratron for Saturn, Bethor for Jupiter, Phaleg for Mars, Och for the sun, Hagith for Venus, Ophiel for Mercury, and Phuel for the moon. Below these names, and around the bottom rim of the bell, he was to write the ancient Hebrew formula Tetragrammaton. As for the wooden handle, on one side of this the necromancer was instructed to carve “Adonai” and on the other side “Jesus.”

When the bell was ready, the magician was to wrap it up in a swatch of green taffeta, and under cover of darkness take it to the cemetery. There, he dug a hole in a gravesite and buried the bell in the dirt for one week. In theory, lying undisturbed in the grave this way, the bell absorbed from the neighboring corpse “emanations and confluent vibrations” which would give it “the perpetual quality and efficacy requisite when you shall ring it for your ends.”

When it came time to dig up the bell and ring it, the necromancer had to don ceremonial clothes (much like a toga) and hold the bell in his left hand and a parchment with signs of the seven planets on it in his right. The deceased, whose grave the bell had been buried in, would hear this sympathetic ringing and be compelled to come forth and answer its summons.

The Necromantic Bell of Girardius. Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, manuscript No. 3009 (eighteenth century).

**

DR. DEE AND MR. KELLEY

In all the annals of the occult, there is no more unusual pair than Dr. John Dee, unofficial astronomer to Queen Elizabeth I, and Edward Kelley, the unscrupulous scryer, or crystal gazer, with whom he formed a long, and tempestuous, alliance.

Dr. John Dee, by all accounts, was a serious and devoted scholar all of his life. Born in 1527 to a minor functionary at the court of Henry VIII, he soon distinguished himself at his studies, attending Cambridge University at the age of fifteen (where he records in his diary that he studied up to eighteen hours a day) and graduating with his bachelor of arts two years later. Already an avid student of astronomy, in subsequent years he traveled

the Continent, learning all that he could, meeting with other scholars, scientists, and astronomers and absorbing every new discovery they were willing to share with him.

Among his most valued prizes were two Mercator globes, which he acquired from the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator himself and brought back to England, and a treatise on magic which he came across, quite by chance, while browsing through the bookstalls in Antwerp. Written by Trithemius, the Benedictine abbot of Sponheim-on-Rhine, this treatise on natural magic, entitled

Steganographia,

made the most powerful impression on Dee; indeed, he wrote an enthusiastic letter about it to the influential statesman Sir William Cecil, in which he claimed that the book’s “use is greater than the fame thereof is spread.” Inspired by what he found in its pages, he wrote in twelve feverish days his own work,

Monas Hieroglyphica,

on the correlation between numbers and various arcane magical practices. Though no one has ever been able to decipher with absolute assurance its true meaning, Sir William declared that Dee’s book was “of the utmost value for the security of the Realm.”

But for all his intellectual gifts and growing reputation as astronomer, Dee hungered after knowledge that he could not discover—the secret of the philosophers’ stone, for instance—and talents he could not acquire, most notably second sight. He had become terribly interested in crystallomancy and spent hour after hour gazing into a convex mirror—his “magic glass"—that he believed had been bestowed upon him by the angel Uriel. But only once did he catch a fleeting glimpse of something, barely discernible, in the depths of the glass; he became convinced that if he was ever to make any headway in the unseen world, he would need an assistant—someone with the powers he lacked, whose visions, and conversations with the angels, he could record, analyze, and interpret.

Enter Edward Kelley. Dee had already gone through a couple of assistants, of insufficient ability, before Kelley got wind of the opening and introduced himself. Up until that time, Kelley, a swarthy young Irishman, had not had the most illustrious career;

at one time an apothecary’s apprentice, he had turned his hand instead to forging and counterfeiting. Convicted for those crimes, he’d had his ears cut off. When he presented himself to Dee in 1582, it was as a scryer, someone who could see and hear the denizens of the otherworld. Dee, wanting to make sure this new applicant understood exactly what kind of service he was entering into, explained that he did not consider himself a magician—the term carried some evil connotations and, depending on how the civil authorities were disposed at any particular time, grim penalties—and that before he made any attempts at crystal gazing, or whatever, he always asked for divine assistance. Kelley put Dee’s mind to rest on that score, dropping to his knees and praying for the next full hour, before looking into the magic glass and describing what he saw.

Dee couldn’t have been more excited.

What Kelley claimed to see there was a childlike angel, imprisoned in the glass, struggling but unable to make its voice heard. From the description Kelley gave, Dee identified the figure as Uriel. Dee, who was fifty-five years old at the time and beginning to despair of ever making his big breakthrough, welcomed Kelley not only into his employment but into his home, too. Dee’s much younger wife (whom he had married after his first wife died of the plague) was none too happy about the new domestic arrangement, but for the sake of her husband’s career, she was prepared to go along. Later, she’d come to regret it.

Kelley, who wore a black cap to conceal his missing ears, spent the next several years communicating with angels and spirit guides for Dee and the many notable patrons they were able to acquire. Among the spirits Kelley spoke for was “a Spiritual Creature,” as Dee described her, “like a pretty girl of seven or nine years of age,” by the name of Madimi. (Dee named one of his eight children after her.) While Kelley relayed Dee’s questions and related Madimi’s answers, Dee made careful transcripts of the conversations. But despite her great willingness to chat, Madimi’s pronouncements weren’t all that revealing.