Raising Hell (5 page)

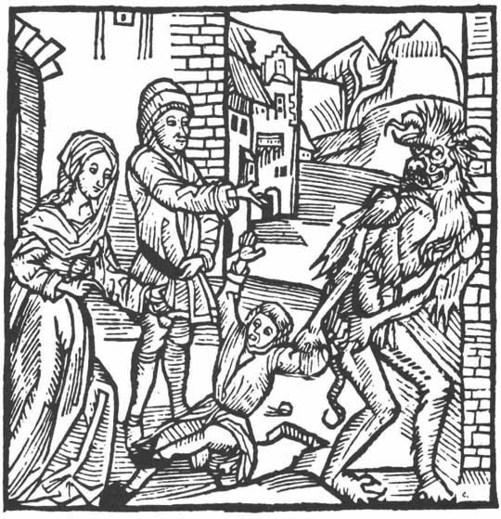

Demon carrying off a child promised to the Devil. From Geoffroy de Latour Landry’s

Ritter vom Turn,

printed by Michael Furter, Basle, 1493.

*

Le Dragon rouge

even includes a prayer, which serves as a kind of insurance policy. Right after making his unholy pact, the sorcerer was advised to declare (out of the demon’s earshot, of course), “Inspire me, O great god, with all the sentiments necessary for enabling me to escape the claws of the Demon and of all evil spirits!” How well this prayer worked, however, was up for debate.

THE OCCULT PHILOSOPHY

Of the many tomes published over the centuries purporting to explain the workings of the unseen world, the three-volume

De Occulta Philosophia,

or

The Occult Philosophy,

was one of the most important and, in its own way, authoritative. Written in 1510 by the sorcerer best known as Agrippa von Nettesheim, it wasn’t published until 1531—and even then it brought the author far more trouble than praise.

Though Agrippa had only been in his early twenties when he wrote it,

The Occult Philosophy

was a mature compendium of magical practice and theory. A brilliant young scholar born in Cologne in 1486, Agrippa started out by studying the approved subjects, such as Greek philosophy and Latin, but his interests were far-ranging, and his natural inclination was toward the mysterious and undiscovered. Like many a young man, he wanted to make his mark in the world, and in the arena of the occult, where everything from theology to alchemy met and mingled, he thought he’d found it.

Despite its increasingly bad reputation, magic, Agrippa declared, had nothing to do with demons and devils; it wasn’t a means to do evil or to invert the natural order. If anything, Agrippa argued in his book, magic was a way to understand the cosmos, as God had created it, and by extension to understand God himself. Man, he contended, “is the most express image of God, seeing man containeth in himself all things which are in God. . . . Whosoever therefore shall know himself, shall know all things in himself; especially, he shall know God, according to whose Image he was made.”

The occult, in Agrippa’s view, was a science all its own, using the more traditional branches of knowledge in a new and different fashion. It employed physics, as it was then understood, to study the nature of things; mathematics to plot the movements of the planets and stars; theology to cast a light on the human soul and on the spiritual world inhabited by angels and demons.

Furthermore, Agrippa believed that all things, animate or not, had a soul, or spiritual essence, and that all of these souls, such as they were, contributed to one vast oversoul. This, he believed, explained the miraculous properties he attributed to everything from garden herbs to precious stones; they contained powers that, however dormant, could be called forth and put to use by a sufficiently skilled magician. There were correspondences and harmonies between all sorts of things, which, if properly understood, could solve a whole host of problems and cure almost any illness.

For instance, a woman who did not wish to become pregnant could prevent it by drinking a dose of mule urine every month. (Mules are sterile.)

A man who wanted to become invisible could wear the stone known as heliotrope, as it reputedly conferred that power.

Anyone suffering from a loss of sight was advised to procure a frog’s eye, as frogs have big eyes and can see even in the dark.

Everything from the constellations to the commonest lump of coal was bound up in Agrippa’s great scheme: “The stars consist equally of the elements of the earthly bodies and therefore the ideas (powers and nature) attract each other. Influences only go forth through the help of the spirit but this spirit is diffused through the whole universe and is in full accord with the human spirit. Through the sympathy of similar and the antipathy of dissimilar things, all creation hangs together; the things of a particular world within itself, as well as the congenial things of another world.”

It was up to the magus to comprehend, interpret, and manipulate this fantastically complicated web of life.

AGRIPPA THE MAGICIAN

For all his protestations to the contrary, Agrippa managed to cultivate a pretty fair reputation for black magic and sorcery. Although he claimed to be firmly on the side of the angels, throughout his lifetime he was dogged by reports that he had

consorted with demons and used his powers for nefarious purposes—reports he didn’t go too far out of his way to quash. Some of these stories were later recycled by Goethe and attributed to his title character Faust.

At many inns where Agrippa stayed, for instance, there were stories that he had paid his bill in perfectly good coins, which, once he’d checked out, turned to worthless shells.

There was the magic mirror in which Agrippa could conjure up images and visions. The lonely Lord Surrey, it was said, had seen his lovely mistress, Geraldine, pining for him in this looking glass.

And then there were all the reports that Agrippa had had contact with the dead; to please a crowd gathered by the elector of Saxony, he summoned the shade of the great orator Cicero, whose eloquence moved the members of the rapt audience to tears.

He was also capable, it was said, of divination. By spinning a sieve on top of a pivot, he could ferret out guilt: Agrippa claimed to have used this method three times in his youth. “The first time,” he wrote, “was on the occasion of a theft that had been committed; the second on account of certain nets or snares of mine used for catching birds, which had been destroyed by some envious one; and the third time in order to find a lost dog which belonged to me and by which I set great store.” Although the system worked perfectly all three times, he claimed that he had given it up, anyway, “for fear lest the demon should entangle me in his snares.”

This wouldn’t be the only time Agrippa reputedly stepped back from the brink. Everywhere he went, for instance, he was accompanied by a big black dog (in some accounts, two), which many claimed was his familiar (unholy helper). As legend has it, one day Agrippa decided he had fallen too deeply into the clutches of the Devil, and he ordered the demon dog to leave his side then and there. The dog, obedient to the last, ran downhill to the river Saône, hurled itself in, and disappeared.

But the most famous story involved Agrippa’s student lodger, who waited until Agrippa went out one day, then wee-died the key to his workroom out of his unsuspecting wife. The

student couldn’t wait to sit down at Agrippa’s desk and pore over the books of magic lying open all around. He was in the middle of one, reading the passages under his breath, when there was a knock at the door. The student didn’t answer, the knock came again—and the door was opened by a demon. “Why have you summoned me?” the demon asked, and when the terrified student couldn’t come up with an answer, the demon, furious at being called up for no purpose, and by a rank amateur to boot, leapt on the student and choked him to death.

When Agrippa got back and found the body, he was immediately afraid that the murder would be pinned on him. But it didn’t take him long to figure out who’d really done it. He summoned the same demon to return to the study—only this time, the demon was given explicit orders by a master magician; he was told, in short, to revive the student and walk him up and down the town market for a short while, long enough for everyone to see him hale and hearty. The demon did it, then allowed the boy to fall over dead of an apparent heart attack. It was only on closer inspection of the body that the strangulation signs were seen. The people, in an outrage, chased Agrippa out of town.

MAGIC CANDLES, MAGIC HANDS

Although sorcerers all had their own favorite magical devices, there were a couple of items that were something like staples of their art. If they couldn’t manufacture these, they could hardly be expected to perform the more elaborate feats.

One such standard was the Magic Candle, which was used to uncover hidden treasure. A recipe for making the candle was included in a book called

Secrets merveilleux de la magie naturelle et cabalistique du Petit Albert,

published in Cologne in 1722. (The book, quite popular with the sorcery crowd, was usually referred to as simply

Le Petit Albert.

) The candle was to be made of human tallow and wedged upright in a curved piece of hazel wood. (A diagram was included in the book.) If you then took

the candle underground and lighted it there—presumably in a cave, burial vault, castle keep—it would sputter noisily and throw off a bright light whenever treasure happened to be buried nearby. The closer you got to the secret cache, the brighter the candle would burn; when you got right up to it, however, the candle would suddenly go out. That’s when you knew it was time to start digging.

But there were some precautions to take. For one thing, it went without saying—though

Le Petit Albert

said it—you should keep several other candles or lanterns burning at all times so that you weren’t suddenly pitched into the dark. More important, if you thought there might be a chance the treasure was being guarded by the souls of the dead, these extra candles had to be made of wax alone and blessed. If you did run into some guardian spirits, it was wise to ask them if there was anything you could do “to help them to a place of untroubled rest.” Whatever they asked you to do, you were advised to do it, without fail.

The Magic Candle usually had a companion piece in something called the Hand of Glory; together, they often occupied pride of place on a sorcerer’s mantel. But the Hand was used for far more nefarious purposes, as is evident from its preparation alone. The first thing you had to do was go to a gallows near a highway and cut off the hand—either one would do—of a hanged felon. Using a strip of the burial shroud to wring it dry of any remaining blood, you then put the hand into an earthenware pot, filled with a concoction of herbs and spices, and left it to marinate for two weeks. The next step was to take it out and expose it to bright sunlight until it was good and dry. If the weather wasn’t cooperating, it was permissible to heat it up in an oven, along with fern and vervain.

What you had now was the perfect, if somewhat grisly, candlestick: if you stuck into it a candle made from the fat of a hanged man, mixed with virgin wax, sesame, and ponie (ponie is an obscure term, but it probably referred to horse dung), you could cast a spell over the inhabitants of any house you chose, rendering them motionless and insensible. The advantages to

this—burglary chief among them—are pretty clear. For as long as the candle burned outside their house, the residents would be powerless to protect themselves or their possessions.

According to one account, from the sixteenth-century demonologist Martin del Rio, a thief once lit the Hand of Glory outside a family’s home, but he was observed by a servant girl. While he was busy ransacking the house, she was desperately trying to put out the candle. First she tried blowing it out, to no avail. Then she doused it with water, which didn’t work; then she tried beer, which also didn’t work. Milk, for unknown reasons, did. The moment the candle was extinguished, the family awoke and caught the thief red-handed; the maid was, of course, rewarded for her bravery and quick thinking.

There was, however, a kind of home security system you could install to ward off anyone using the Hand of Glory. During the dog days of summer (generally reckoned From July 3 to August 11), you had only to prepare an unguent from three ingredients—the gall of a black cat, the blood of a screech owl, and the fat of a white hen—and then smear it over the thresholds, window frames, chimney stack, and any other place that someone might use to get into the house. Once the unguent was down, the house was impenetrable to anyone attempting to use the Hand of Glory.

CURSES AND INCANTATIONS

The resourceful sorcerer always had at hand a variety of spells, culled from his manuals and his own experiments, with which he could achieve his desired aims. Sometimes these aims were indeed diabolical—raising the dead, conjuring demons—but sometimes they were more mundane, such as predicting a needed change in the weather or helping a “client” to find a lost object. Selling their services, sorcerers could be called upon to inflict a curse or remove one, to do evil or ward it off. In a way, they were something like brokers, making money off the transaction whichever way it went. An unscrupulous sorcerer

(never very hard to find) could even cast a curse on someone, rendering him impotent or his fields barren or his prospects ruined, and then offer to put things right again—for a fee.

It might be thought of as an early form of the protection racket.

If someone was truly unlucky, he might find himself caught between two

competing

sorcerers, one laying a curse on him and the other trying to get it off. Setting things straight could cost the patient a pretty penny.

And then, on occasion, sorcerers found themselves in direct conflict with each other, testing their powers against a member of their own secret fraternity. In a celebrated case recounted by Olaus Magnus in his

Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus

(1555), a magician named Gilbert challenged his master, a powerful sorcerer named Catillum, who responded by imprisoning Gilbert in an underground cavern, where he was “shackled by two wooden bars inscribed with certain Gothic and runic characters in such manner that he could not move his limbs.” According to the legend, Gilbert would remain a prisoner there until another sorcerer, one even more powerful than Catillum, could break the spell.