Raising Hell (6 page)

Sorcerers also tended to specialize, to some extent based on where they lived. Those who lived near the sea, for instance, were often called on to do something about things like winds and currents. They were asked to speed some ships on their way, and sink others, to stir up tempests or calm the turbulent waves. In seafaring nations, particularly the Scandinavian countries, sorcerers did a lively trade selling favorable winds; it was thought possible, for example, to tie up the winds in a knotted rope. A ship’s captain could buy such a rope, and when he needed a gentle west-southwesterly breeze, he had only to undo the top knot; for a strong northerly wind, the second; for a terrible storm, the third. (That third knot, presumably, was seldom untied.) In Scotland, the wives of sailors thought they could conjure up favorable winds on their own; stealing into a chapel after the regular service had been performed, they blew the dust on

the floor in the direction that their husbands’ ships were traveling.

Witch brewing up a storm. From Olaus Magnus’

Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus,

Rome, 1555.

*

Magicians who lived inland were called on to do everything from improving the crops to sweetening the milk of the herdsman’s cows. In times of plague, they could be accused of having caused the epidemic—or they could be begged to eradicate it. In times of war, they could be asked to inflict curses on the enemy—or heal the wounds of their compatriots. Sorcerers were thought capable of stanching the flow of blood from a wound or magically removing a bullet or arrowhead. They could start a fire, and they could put one out. They could be, at once, the most dreaded foe or most prized ally. To stay on the safe side, it was always wise to give them a wide berth and a polite tip of the hat.

Especially as they often had unpleasant friends that they could call upon.

Thomas Aquinas, in his

Sententiae,

declared in no uncertain terms that “magicians perform miracles through personal contracts made with demons.” If that wasn’t clear enough, Ebenezer Sibly, author of

The New and Complete Illustration of the Occult Sciences

(1787), warned his own readers that while sorcerers

and witches could call upon all sorts of spirits and apparitions, there were three types in particular that were most likely to do the magicians’ bidding.

Sorcerer selling a bag of wind (tied up in three knots of a rope). From Olaus Magnus’

Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus,

Rome, 1555.

*

First, according to Sibly, there were the astral spirits, who haunted mountaintops and deep, dark forests, ancient ruins, and any spot where someone had been killed. Then there were the igneous spirits, of a “middle vegetative nature,” but “obsequious to the kingdom of darkness.” These monstrous creatures, with a naturally nasty turn of mind, were particularly receptive to skillful conjurers. Last, there were the terrine spirits, who seemed to have an innate hatred of mankind. Maybe it was because of where they lived. Confined to the “hiatus or chasms of the earth,” caves and mines and tunnels, they were simply chafing at the bit to cut loose and create some real mayhem. Some of their attacks were recorded in a treatise entitled

De Animantibus Subterraneis

(On Subterranean Hauntings) in 1549 by a German metallurgist named Georgius Agricola.

According to Agricola, the workers in a mine called the Rosy Crown, in the district of Saxony, were suddenly surprised by a dreadful apparition, a “Spirit in the similitude and likeness of a horse, snorting and snuffling most fiendishly with a pestilent blast.” Its breath was so noxious that a dozen miners died on

the spot, while the others scrambled up to safety, screaming in terror. And despite the fact that the mine was rich with ore, no one would ever go back down again to dig it. In Schneeberg, Saxony, the mine of St. George was also haunted by a terrine spirit, but this one took the shape of a man in a big, black cowl. When the miners encountered him, he grabbed hold of one of them and hurled him at the roof of the mine. By the time he came down, bruised and battered, the others had already taken their leave.

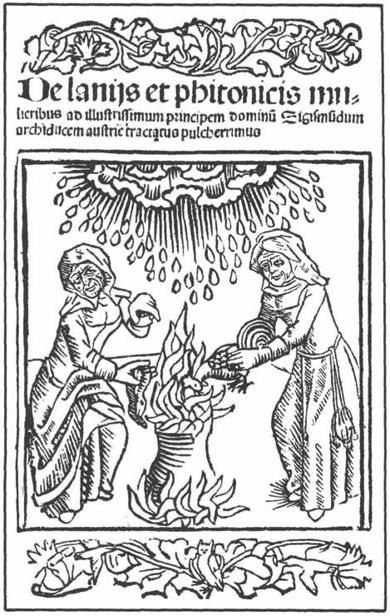

Witches brewing up a hailstorm. From the title page of Ulrich Molitor’s

De Ianijs et phitonicis mulierbus,

printed by Cornelius de Zierikzee, Cologne, 1489.

*

But all of these spirits, in the view of Sibly, existed in a state of “continual horror and despair” themselves. “That they are materially vexed and scorched in flames of fire,” Sibly wrote, “is only a figurative idea, adapted to our external senses, for their substance is spiritual, and their essence too subtile for any external torment. The endless source of all their misery is in themselves, and stands continually before them, so that they can never enjoy any rest, being absent from the presence of God; which torment is greater to them than all the tortures of this world combined together.”

The conjurers who called upon them, for whatever purpose, ran the risk of sharing their fate.

LOVE AND DEATH

Human nature being what it is, there were two areas that the sorcerer was most often called on to explore—one was love, the other death. And he had at his disposal a whole raft of potions and philters, talismans and incantations.

When it came to winning a woman’s love, there were easy methods—and there were hard. Among the easier ways of winning her heart, there was what might be called the horoscope ploy. As outlined in an eighteenth-century French manuscript now in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, “To gain the love of a girl or a woman, you must pretend to cast her horoscope—that is to say, when she shall be married—and must make her look right into your eyes. When you are both in the same position

you are to repeat the words, ‘Kafe, Kasita non Kafela et publia filii omnibus suis.’ These words said, you may command the female and she will obey you in all you desire.”

Want something even easier? Rub the juice of the vervain plant on your hands, then touch the one you love.

Or try touching her hand while saying,

"Bestarberto corrumpit viscera ejus mulieris”

("Bestarberto entices the inward parts of the woman").

If the simpler methods aren’t working, you can always resort to a philter, a love-inducing potion made from wine mixed with assorted herbs and drugs. In the tragedy of Tristan and Iseult, a philter that Iseult’s mother had planned for King Mark to drink is actually consumed by Tristan and Iseult—who wind up paying for the mistake with their lives. In Richard Wagner’s

Gotterdämmerung,

Siegfried’s affections are diverted from Brünnhilde to Gutrune after he quaffs a magic philter. The recipe for such a philter is included in a seventeenth-century manuscript called the

Zekerboni,

written by a self-styled “Cabbalistic philosopher” named Pietro Mora: it requires “the heart of a dove, the liver of a sparrow, the womb of a swallow, the kidney of a hare,” all reduced to an “impalpable powder,” and added to an equal portion of the manufacturer’s own blood. The blood, too, must be dried to a powder. If a dose of this concoction is then slipped into the intended’s wine, “marvellous success will follow.”

A simpler, though no less revolting, recipe is offered by Albertus Magnus in his “Of the Vertues of Hearbes.” After taking some leaves of the periwinkle and mashing them into a powder with “wormes of the earth,” add a dash of the succulent commonly known as houseleek. Use the result as a sort of condiment with the meat course and then just watch the sparks fly.

The plant kingdom actually yielded any number of aphrodisiacs, which included lettuce, jasmine, endive, purslane, coriander, pansy, cyclamen, and laurel. The ancient Greeks included carrots, perhaps because of their shape. The poppy and deadly nightshade plants were also thought helpful in the quest of love, but less because they inspired ardor than because they could render someone unconscious and therefore vulnerable.

In the Middle Ages, the mirror method was recommended to many a lovesick swain. The idea was to create in the looking glass itself a kind of link between yourself (the owner of the mirror), the woman you desired, and the act of making love. How did you do this? Simple.

First you bought a small mirror (without haggling over the price), and you wrote the woman’s name on the back of the glass three times.

Then you went out looking for a pair of copulating dogs and held the mirror in such a way that it would capture their reflection.

Finally, you hid the mirror in some spot you were sure the woman would be passing frequently and left it there for nine days. After that, you could pick it up again and carry it in your pocket. Without knowing why, the woman would find herself irresistibly attracted to you.

Conversely, if a woman had her eye on an elusive male, she could win his love by serving him, as it were, a casserole of herself. First, she had to take a very hot bath and then, as soon as she got out, cover herself with flour. When the flour had soaked up all the moisture, she took a white linen cloth and wiped all the flour away; then she wrung out the cloth over a baking dish. She cut her fingernails and toenails, plucked a few stray hairs from all parts of her body, burned them all to a powder, then added them to the dish. Stirring in one egg, she baked the whole awful concoction in the oven, and served it to the object of her affections. Assuming he could get a mouthful down, he’d be hers forever.

Casting a death spell was, for obvious reasons, a more dangerous matter than magical matchmaking. If you tried it, and were found out, the penalty could be your own life. As a result, the death spells were often reserved for very high-stakes games—most notably, royal thrones and titles. If you were a king or queen, chances are there was some malcontent in your kingdom casting a death spell your way.

In 1574, Cosmo Ruggieri, a Florentine astrologer at the

French court of Charles IX, was accused of having created a waxen image of the king and then beating it on the head. He then made the mistake of asking around if the king was having any pains in his head of late—and was quickly placed under arrest. (It didn’t help that the king died that same year.)

In 1333, Robert III of Artois was banished from France by Philippe VI for forging land deeds to support his claim to the title of count; in revenge, Robert tried to cast a death spell on the French king, but his plot was revealed to the king by Robert’s priestly confessor.

And around 1560, the Privy Council of England was thrown into a panic when a waxen image of Queen Elizabeth, with a long needle stuck through its heart, was discovered in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Her advisers quickly called in Dr. John Dee for an immediate consultation with the young queen, who was dreadfully worried. Dee met with her in her private garden in Richmond, explained the mechanics of the death spell, and reassured her that it could be counteracted. As she reigned until 1603, he clearly did a good job of it.

Although there were plenty of methods for casting the death spell, the waxen image was one of the oldest and most popular. A little wax doll was made, representing the person on whom you wished to inflict the harm, which was then pierced with needles to inflict, by magical transmission, actual physical damage or death. If possible, it was a good idea to dress the figure up in the style of the intended victim; in a French engraving, Robert of Artois has dressed his figure of the king in the appropriate court costume.