Raising Hell (22 page)

As for Mora, he was vehemently denouncing the raid and declaring his innocence when one of the magistrates happened to knock on a wall, which gave off a hollow sound. Careful inspection revealed a secret door, hidden by trick carpentry; behind the door there were extensive cellars, where the magistrate and his men found what they’d been looking for. Besides the High Altar of Satan, they discovered a padlocked chest containing silver-tipped wands, magic crystals, and amulets engraved with the names and sigils of various devils. In a cupboard they found an array of poisons and other loathsome substances, arranged just as more wholesome ingredients might be in an apothecary’s shop. Mora was carted off for further interrogation.

Before long, he had confessed to being the grand master of a secret group of Satanists, whose aim was to decimate the whole city of Milan. To that end, he and his confederates had smeared their deadly potions on door knockers and gates; they had poured poison into the springs that fed the town; they’d mixed ergot with the baker’s flour; they’d even polluted the stoups of holy water in the cathedral with oil of vitriol. But none of this was so deadly as the work they’d done under the guise of charity; according to Mora, they’d taken clothing and bed

linens from the dead and dying, then distributed them among the living and so-far-uninfected people in the poorer quarters of the city.

Mora and his confederates were summarily sentenced to death for their crimes. Mora’s house was then burned to the ground, and a tall column, inlaid with a bronze tablet detailing the evils he had brought on Milan, was raised above the cinders.

THE MAN WHO COULD NOT DIE

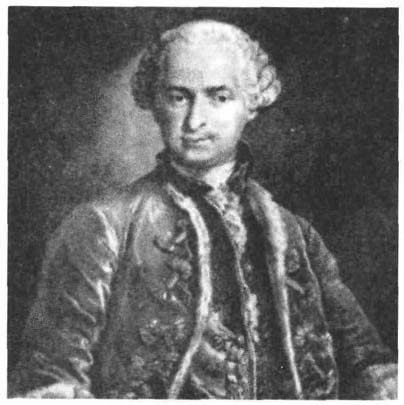

Though everything about him, including his name, often changed, he was known for most of his life as the comte de St.-Germain, and he claimed to have discovered, among other things, the elixir of life. In the royal courts of eighteenth-century Europe, he was sometimes hailed as a hero and genius—Frederick the Great of Prussia called him “the man who cannot die"—and sometimes persecuted as a charlatan and fraud.

What is probably true is that he was born in the town of San Germano, Italy, the son of a tax collector, around the year 1710. But he drew such a veil over his actual past that little more is known of his origins. (He was possibly of Portuguese Jewish extraction.) A lively, dark-haired man who often wore clothes encrusted with valuable jewels, he first made a name for himself some thirty years later, in Vienna, where he became a friend of various Austrian and French aristocrats; in fact, it was one of these French noblemen, Charles de Belle-Isle, marshal of France, who brought him to France and introduced him into the circle of Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour.

There, he endeared himself by bestowing on the king a diamond worth ten thousand livres and by assuring the other members of the court that he had a miraculous, secret method for removing the flaws from any stone. He was by all accounts a magnificent conversationalist (fluent in as many as eleven languages), a talented musician (playing the violin and harpsichord),

a historian, scholar, and chemist. Wherever he went—and he seems to have spent his entire life traveling from one patron to another—he set up a laboratory and was reputedly quite skilled in ways of dyeing silk and leather goods.

But his greatest claim was that he had discovered the elixir that granted eternal life. When asked his age, he would merely smile enigmatically and change the subject. But if the conversation turned to historical events, he was known to chime in with anecdotes and purportedly firsthand observations on events from the most distant past and far-off lands. He claimed, for instance, to have had conversations with the queen of Sheba, Christ, and Cleopatra. He also made it known that he had shared his miraculous elixir with his valet; as a result, his valet was once asked if he, too, had been present at these ancient events. “No,” the valet replied, “but you forget—I’ve only been in the count’s employ for one century.” For court ladies, he provided an emollient, free of charge, that he claimed would make wrinkles disappear.

At table, the count was known not only for his wit but for his abstinence. Even when seated at the most elaborately prepared banquets, he would eat and drink nothing, declaring that he lived, instead, on a magical food of his own preparation.

He was extraordinarily popular and might have remained so had he not become entangled in some political and diplomatic intrigue involving a peace between France and England. Having worn out his welcome with Louis XV, he set out for London, then Holland, where he established himself as Count Surmont. There, he spent a decade or so, making a fortune and building factories for dyeing fabrics and for the “ennobling of metals,” before taking off again (under some kind of cloud) for Russia.

Once more, he managed to make friends in high places, and after the Russian army defeated the Turks, he was made a general—General Welldone, he called himself—for the services he had rendered.

The Comte de Saint-Germain, an Eighteenth-century Alchemist. Portrait engraved by Thomas.

**

Still, he couldn’t stay put, but traveled on, to Nuremberg, Paris, Leipzig, before finding his last patron in the landgrave Charles of Hesse, in Schleswig-Holstein. Charles, too, happened to be an ardent alchemist, and together they pursued their occult experiments. But St.-Germain began to suffer from bouts of depression and chronic rheumatism, and after four or five years, he died, cradled in the arms of two chambermaids. Or, at least, that was the official account.

According to other accounts, however, St.-Germain didn’t die at all; there were reports that he was seen in Paris many years later and that he had in fact sent a letter to Marie-Antoinette after the fall of the Bastille: “No more maneuvers,” he warned her. “Destroy the rebels’ pretext by isolating yourself from people whom you do not love any longer. Abandon Polignac and his kind. They are all vowed to death and assigned to the assassins who have just killed the officers of the Bastille.” After the queen’s execution, some people reported that they had seen the count lingering around the Place de la Grève, where the guillotine was still doing its deadly work.

Another story was perhaps even more outlandish. This one claimed that St.-Germain had journeyed to Tibet, where he had become one of the Hidden Masters who later guided the hand of Madame Blavatsky, the founder of theosophy.

FATE AND THE

FUTURE

For the gods perceive what lies in the future, and men what is going on before them, and wise men what is approaching.

Apollonius of Tyana

THE DIVINATORY ARTS

It’s not hard at all to see where the arts of divination came from. For as long as man has wondered whether the battle would be won or lost, whether the crops would fail or flourish, whether his love would be requited or spurned, he has looked for ways to divine—or foresee—the future.

But even if the urge to see into the future is unsurprising, what is surprising—even astonishing—is the number of ways that have been invented to do it. In some respects, the history of man is a long catalog of ingenious methods devised to ascertain just what was around the corner, starting with the ancient study of sacrificial animal bones and continuing today with psychic hot lines on late night TV. The methods have differed, but the purpose has always been the same: to know today what’s going to happen tomorrow.

In general, these divinatory arts have fallen into several broad categories. First, there were omens and auguries, signs of what was to come that were drawn from the observation of natural phenomena. In the ancient world, the shape of a cloud, the scuttling of an insect, the cry of a bird, were all considered predictors of or clues to future events. (Plutarch even had faith in fishes, arguing that because they were mute and so far removed from the heavens, they must have developed some extraordinary skills of reason and intelligence.)

A second category might be called invited guidance—throwing dice or knucklebones, reading playing cards or tea leaves, drawing lots. The ancient Chaldeans, and later Greeks and Arabians, used arrows as divinatory tools, throwing a quiverful into the air, then remarking on the direction and manner in which they fell. (The practice was known as belomancy.)

The third form of divination, one in vogue even today, is the most personal and intuitive of them all. It relies upon self-induced visions, dream analysis, crystal gazing, and/or, with the help of a psychic or reader of some kind, clairvoyance. In an

antique version, the Pythian priestess of Delphi, whose oracles were thought to be divinely inspired, first chewed on a hallucinatory herb, then, while sitting on a tripod above a fuming crevice in the rock, made her cryptic pronouncements; her words were taken down by male priests, who later pored over them to extract the true meaning. (Interpretation, truly, was all: When Croesus, king of Lydia from 564 to 546

B.C.,

asked what would happen if he declared war on the Persians, the oracle said that he would destroy a great empire. Croesus took her words as encouragement, went to war, and succeeded in destroying a great empire, after all—his own.)

Today no one travels to consult with the Delphic oracle anymore, but many people do rely upon the advice and counsel of their astrologer or psychic to guide them in everything from their romantic liaisons to their investment decisions. Even the occupants of the White House have turned to the divinatory trade from time to time; Nancy Reagan reportedly consulted a San Francisco astrologer named Joan Quigley for advice on everything from the scheduling of the president’s diplomatic meetings to the takeoff times for

Air Force One.

Nor have the advances of science and reason—the proliferation of computers and the many forms of instant information retrieval—put a stop to the reliance upon these age-old methods of prediction.

Why haven’t they?

Because for all of our purported enlightenment and technological advancement, one thing—human nature—has remained essentially unchanged. The things we want to know—how will things turn out? does she really love me? should I take the job or not?—are as perplexing as they ever were, and all of the computer programs in the world can’t predict with certainty the outcome or tell us what to do. Indeed, in a world where so many decisions have to be made every day, where the pace of life has increased and the time to ponder has declined, perhaps it’s not surprising that people turn to less rational, more mysterious methods.

What the divinatory arts also promise us, in a way, is a measure of control—if we can foresee events or their outcome,

we can make our plans accordingly. And in an age plagued with dreaded specters ranging from nuclear warfare to AIDS, the search for answers, for an understanding of the greater forces affecting our lives, becomes even more urgent. With so much spinning out of control, it’s important, even vital, to feel that there is still some power we can exert—even if it is only predictive—over our affairs and fortunes.

In that quest, a whole host of divinatory arts has been created over the centuries; in addition to the better-known variations, such as chiromancy (palm reading), cartomancy (tarot and other cards), and astrology, scores of even more baffling methods have emerged over the ages and found, at one time or another, widespread acceptance and use. Some of the more interesting and commonly employed include the following.

Gyromancy

used a sacred circle to receive messages and portents from the unseen world.

To begin with, a circle was made on the ground, and its border was marked with letters of the alphabet or other, more mystical symbols. The practitioner then entered the circle and began to march around and around inside the circle, making himself progressively dizzier. Each time he stumbled, the letter or symbol that he landed on was duly noted; once he couldn’t get up and go around anymore, the message was considered complete.

There were two reasons why the dizziness was thought absolutely essential. For one, it was thought to rule out any premeditated or intentional selection of the letters. He was falling down at random. And for another, the very act of turning around, of spinning in place until all balance was lost, was a staple of spells and enchantment since time immemorial. Many sacred dances used the same method to induce a kind of prophetic trance. In fact, it was long thought that fanatics and lunatics, whose movements involved wild spinning and turning with arms extended, were themselves possessed by invisible elements of the spirit world. They weren’t spinning so much as they were being spun.

This belief gained widespread acceptance in the 1400s, when an epidemic of a disease that came to be known as St. Vitus’ dance swept across western Europe. A hysterical form of the neurological disease chorea, it not only caused its victims to run and leap and spasmodically jerk their limbs but also induced hallucinations; when these fantasies were uttered aloud, the auditors considered them prophetic. Sufferers were taken to the chapels of St. Vitus, a little-known Christian saint of the fourth century, who was the guardian of those afflicted with convulsive diseases.