Raising Hell (30 page)

On another, and later, occasion, Nostradamus was walking through the courtyard of a castle in Lorraine when two pigs—one black and one white—ran across his path. To test his guest’s much-vaunted skills, the lord of the castle asked Nostradamus what the fate of the two pigs would be.

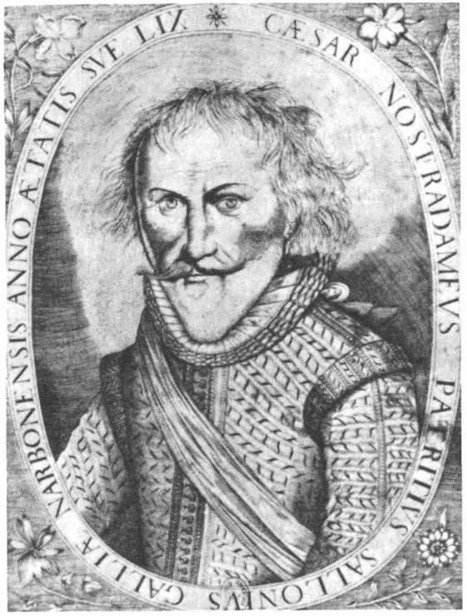

Portrait of Nostradamus at the Age of Fifty-nine. Sixteenth-century print.

**

“The black one we shall eat,” the seer replied, “and a wolf shall eat the white.”

That same day, in an effort to foil the great prophet, the lord privately instructed his cook to kill and cook the white pig and serve it for dinner.

The cook did as he was told, but left the roasted white pig in the kitchen unattended—where a wolf managed to sneak in through the door and gobble it up. The cook quickly killed the black pig and served that one for dinner instead—without advising his master of what he’d done.

The lord, laughing, said to Nostradamus, “Well, you must have been wrong about that wolf eating the white pig because the white pig is what we’re eating now.”

Nostradamus, however, stuck to his guns and said that that was impossible. This was the black pig they were eating.

To settle the question, the lord had the cook brought into the dining room, asked him which pig they were eating, and nearly fell out of his chair when the cook, flustered and fearful, explained what had happened in the kitchen.

But it was his medical skill that eventually brought Nostradamus back to France, where he fought outbreaks of the plague in Marseilles, Aix-en-Provence, and Lyons. (He had already lost his first wife and two children to a previous outbreak.) For his remarkable and brave services, he was awarded a pension and settled in the town of Salon with his second wife. Their house, on a dark and narrow street, had a winding staircase that led to a top-floor study; there, with the rooftops of the town spread out below him, Nostradamus composed his almanacs of astrology and, more important, the prophetic verses that remain his legacy. In two such verses, he described how his visions came, in the still of those midnight hours:

Gathered in night in study deep I sate

Alone, upon the tripod stool of brass,

Exiguous flame came out of solitude,

Promise of magic that may be believed.

The rod in hand set in the midst of the Branches,

He moistens with water, both the fringe and foot;

Fear and a voice make me quake in my sleeves;

Splendour divine! the God is seated near.

Judging from this account, Nostradamus held in his hand a forked wand, much like a divining rod, while surrendering to his divinely inspired visions: “The things that are to happen can be foretold,” he wrote in the preface to his prophecies, “by nocturnal and celestial lights, which are natural, coupled to a spirit of prophecy.” He penned his predictions in four-line verses, which were gathered into groups of one hundred and later published as

Centuries.

The obscurity of their meaning can be attributed in part to the mystery of their origin—the Divine Being is not about to spell things out in the most literal fashion—and partly, as Nostradamus himself confesses, to avoid political and religious repercussions for the seer and his family. Predicting the rise and fall of kings and queens could, for obvious reasons, land one in a dungeon overnight. (As late as 1781, the prophecies were condemned by a papal court, for cryptically predicting the fall of the papacy.)

Nostradamus himself said that his predictions would be borne out over a period of hundreds of years, so that it would take many generations before their truth could in every instance be revealed. Consequently, each generation has pondered their runic utterances and tried to decipher the secret meaning. The quatrains have been thought to predict everything from World War II to the end of the world. And some have indeed been interestingly on target, particularly those that seem to describe the period of the French Revolution, which was still over two hundred years in the future. There is, for instance, one verse (century IX, quatrain 20) that goes:

By night shall come through the forest of Reines,

Two married persons, by a tortuous valley, the Queen a white stone,

The black monk in gray into Varennes,

Elected king, causes tempest, fire, blood, cutting.

Varennes shows up only once in the greater scheme of European history, and that is when the French king Louis XVI ("elected” because he was the only king to hold his title by will of the Constituent Assembly rather than divine right) and his queen, Marie Antoinette, were captured there after their flight. Louis was disguised in gray, the queen was dressed in white, and after they were returned to the maelstrom of blood and destruction they had unleashed, they were themselves (as the last word of the prophecy indicates) cut—beheaded by the guillotine.

And then there are the lines (century III, quatrain 35) that appear to predict the rise of Napoleon:

In the southern extremity of Western Europe

A child shall be born of poor parents,

Who by his tongue shall seduce the French army;

His power shall extend to the Kingdom of the East.

Napoleon Bonaparte was born in Corsica, into an impoverished family. His bold commands won the hearts of the French troops and enabled him to lead them successfully into Egypt (a campaign that even the Directory, which had dispatched them, thought was likely to end in disaster). Whether by luck or something more, Nostradamus had once again managed to hit the nail on the head.

But while it would take centuries for some of his prophecies to be fulfilled, he was renowned in his own day for his ability to cast astrological charts and offer advice of a more immediate and practical nature. Henry II, the king of France, summoned him to Paris and rewarded him for his labors with a hundred gold crowns in a velvet purse; Catherine de Medici, the queen of France and an ardent believer in the occult, provided him with the same amount, and even sent him on to Bloise, to give the royal children a health checkup. When Charles IX succeeded

to the throne, Nostradamus was named physician-in-ordinary to the king himself.

On his death in 1566, a marble tablet was erected to his memory in Salon. The inscription chiseled in the stone read, in part:

“Here lie the bones of the most famous

NOSTRADAMUS

One who among men hath deserved the opinion of all, to set down in writing with a quill almost Divine, the future events of all the Universe caused by the Coelestial influences.”

G

LOSSARY

A guide to terms, titles, and proper names used in the text. A missing date of birth or death means none has been recorded with any certainty.

adept

—one highly skilled in the occult arts

Agrippa

—(1486–1535) Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Agrippa von Nettesheim, German magus, author of

The Occult Philosophy

Albertus Magnus—

(1193–1280) German alchemist, reputedly the inventor of the pistol and cannon

alchemy—

the mystical art of transmuting base metals to gold

alectromancy—

divination using a barnyard cock inside a magic circle

alkahest

—universal solvent searched for by alchemists

Apollonius of Tyana

—Pythagorean philosopher of first century

A.D.,

reputedly able to foretell the future

Aquinas, St. Thomas—

(c. 1227–74) Italian scholastic philosopher and major theologian of Roman Catholic Church

Aristaeus—

prophet, healer, and divinity worshiped in ancient Greece

augurs—

seers and diviners of the ancient world

Avicenna—

(980–1037) Persian physician and philosopher

Bacon, Roger—

(1214–92) English friar and magician

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna—

(1831–91) Russian founder of Theosophical Society

Boehme, Jakob—

(1575–1624) German mystic and philosopher

Brahe, Tycho—

(1546–1601) Danish astronomer and astrologer, author of extensive planetary tables

Cabbala—

body of mystical Jewish writings and theosophy

Cagliostro—

(1743–95) a celebrated mystic, healer, and magician

Cardan, Jerome—

(1501–76) a.k.a. Girolamo Cardano, Italian physician, astrologer, and mathematician

Cellini, Benvenuto—

(1500–71) Italian goldsmith and artisan

Chaldeans

—ancient Semitic people who lived in what was then Babylonia (a region of lower Tigris and Euphrates valley)

Chambre Ardente—

the Burning Court of Louis XIV, to prosecute poisoners and others

Chiancungi

—an Egyptian fortune-teller who became famous in eighteenth-century England

chiromancy

—divination by studying the hand (palm reading)

Crowley, Aleister—

(1875–1947) British occultist and mage

Cyprian, St.—

(c.200–58) early church father and martyr

Dashwood, Sir Francis—

(1708–81) English aristocrat who founded a diabolical order in Buckinghamshire

Dee, Dr. John—

(1527–1608) English alchemist and necromancer

del Rio, Martin Antoine—

(1551–1608) Jesuit scholar, renowned prosecutor of sorcerers and witches

deasil—

going to the right, the direction of good

Eckhart, Johannes—

(c. 1260–?1327) Meister Eckhart, Dominican preacher, father of German mysticism

elementals—

minor spirits of earth, air, fire, and water

ephod

—white linen vestment worn by a necromancer

Fludd, Robert—

(1574–1637) English alchemist and Cabbalist, author of

The History of the Microcosm and Macrocosm

Fortune, Dion—

(1891–1946) English occultist and author of

Psychic Self–Defense

Fox sisters—

Kate, Margaret, and Leah, who founded American spiritualism in Arcadia, New York, in 1848

Freemasons—

ancient and powerful secret society, practicing mystical rites

Galen—

(c. 130–c. 200) Greek physician and writer on medicine

Gaufridi, Father Louis—

French priest executed for witchcraft in 1611

Girardius—

inventor in 1730 of the necromantic bell

Glauber, Johann Rudolf—

(b. 1603) German author of many texts on medicine and alchemy, including

Miraculum Mundi

Gnosticism—

mystical religion that flourished in the first and second centuries

A.D.

Gowdie, Isabel—

Scottish witch of the sixteenth century

Grand Copt—

the prophet Enoch, founder with Elijah of the Egyptian rites for Freemasons

Grandier, Urbain—

priest accused of bewitching nuns in Loudun, executed in 1634

grimoire

—a manual of black magic

Guazzo, Francesco-Maria—

Italian friar, expert witness in seventeenth-century witch trials

gyromancy—

divination by means of spinning in a circle marked with letters and occult symbols

Hand of Glory—

a hanged man’s hand, used to cast spells

Helmont, Jan Baptista van—

(1577–1644) Dutch alchemist and doctor

hexagram—

six–pointed star, also known as Seal of Solomon

homunculus—

artificial human, or dwarf, made by alchemy

Iamblichus—

(c.250–c.326) Neoplatonist philosopher and theurgist

Kelley, Edward—

(1555–93) English alchemist and scryer, accomplice to Dr. John Dee

Knights Templar—

military and religious order founded to protect Christian pilgrims

Kunkel, Johann—

(1630–1703) German chemist and alchemist

Lévi, Eliphas—

(c. 1810–75) French occultist and author of

The Doctrine and Ritual of Magic

liber spirituum—

the book of spirits, kept by sorcerers

magus—

a master magician (plural, magi)

Maimonides—

(1135–1204) Jewish philosopher and theologian

Malleus Maleficarum—

manual of witchcraft, aka

The Witches’ Hammer,

written by Jakob Sprenger and Heinrich Kramer (1486)

Mathers, MacGregor—

(d. 1918) founder of the Order of the Golden Dawn

Mora, Pietro—

alchemist and poisoner in seventeenth–century Milan