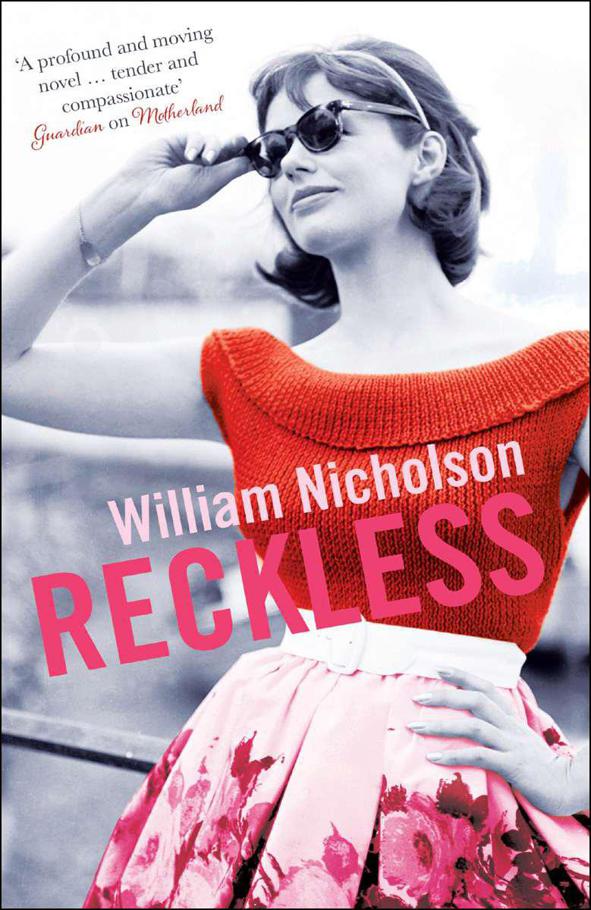

Reckless

Authors: William Nicholson

PART TWO: Deterrence January 1961 – June 1962

PART THREE: Mutually Assured Destruction July – September 1962

PART FOUR: Retaliation October 1962

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Quercus Editions Ltd.

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London

W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2014 William Nicholson

The moral right of William Nicholson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 78206 642 2

TPB ISBN 978 1 78206 643 9

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78206 644 6

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Also by William Nicholson

The Trial of True Love

The Society of Others

The Secret Intensity of Everyday Life

All the Hopeful Lovers

The Golden Hour

Motherland

Books for children

The Wind Singer

Slaves of the Mastery

Firesong

Seeker

Jango

Noman

Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love. From it a quotation:

‘As East and West

In all flat maps – and I am one – are one,

So death doth touch the resurrection.’

That still does not make a Trinity, but in another better known devotional poem Donne opens, ‘Batter my heart, three-person’d God … ’

J. Robert Oppenheimer, on why he named

the first atom bomb test ‘Trinity’

Batter my heart, three-person’d God; for you

As yet but knock …

Yet dearly I love you, and would be loved fain,

But am betrothed unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie me, or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthral me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

John Donne, Holy Sonnet XIV

Tea at Cliveden: September 1943

Rupert Blundell did not want to go to tea with the princess. He was unsure how to address her, and he was shy with girls at the best of times. Lord Mountbatten, his commanding officer, brushed aside his murmurs of dissent.

‘Nancy wants some young people,’ he said. ‘You’re a young person, and you’re available.’

Rupert was twenty-six, which felt to himself both young and old. Princess Elizabeth was of course much younger, but being heir to the throne she was unlikely to be short of savoir-faire.

‘And anyway,’ said Mountbatten, ‘you’ll like Cliveden. They still have a pastry cook there, and it has one of the best views in England.’

So Rupert put on his rarely worn No.2 dress uniform, which fitted poorly round the crotch, and reported to COHQ in Richmond Terrace. A car was to pick him up from here and drive him to Cliveden, Lady Astor’s country house.

‘Very smart, Rupert,’ said Joyce Wedderburn, passing through on her way back to her office.

‘I’m under orders,’ said Rupert glumly.

‘Aren’t the trousers a bit small for you?’

‘In parts.’

‘Well, I think you look very dashing.’

She gave him one of her half-smiles that he could never interpret, that suggested she meant something other than what she seemed to be saying. But Rupert liked Joyce. He could talk to her more freely than to the other girls. There was no nonsense about her, and she had a fiancé in the Navy, in minesweepers.

The car arrived: a Humber Imperial Landaulette, driven by one of Lady Astor’s chauffeurs. Its rear hood was down, and sitting in the wide back seat was an American officer of about Rupert’s own age. He introduced himself as Captain McGeorge Bundy, an aide attached to Admiral Alan R. Kirk, commander of the Allied amphibious forces.

‘Call me Mac,’ he said.

He revealed to Rupert that they were to represent the wartime allies at this tea party. There was to be a Russian too. All this in a crisp monotone, as if to impart the information in the most efficient way possible.

The Russian was news to Rupert.

‘I’ve no idea what we’re supposed to do,’ he said. ‘Have you?’

‘I think the idea is the princess wants to meet people nearer to her own age,’ said Bundy.

‘What for?’

‘Maybe it’s a blind date.’ Bundy smiled, but with his mouth only. ‘How’d you like to marry your future queen?’

‘God preserve me,’ said Rupert.

Mac Bundy was trim and sleek, with sand-coloured hair brushed back smoothly over his high forehead. He wore wire-rimmed glasses. His navy-blue uniform had every appearance of being excellently cut. Looking at him, Rupert felt as he did with so many Americans that they were the physically perfected version of the model, while he himself was a poor first draft.

He shifted on the car seat to ease the itching in his trousers. The landaulette drove through Hyde Park, past the Serpentine. From where he was sitting he could see himself reflected in the

driver’s mirror: his long face, his thick-rimmed spectacles, his protruding ears. He looked away, out of long habit.

‘So who got you into this?’ said Bundy.

‘Mountbatten. He’s a friend of Lady Astor’s.’

‘Kirk fingered me,’ said Bundy, adding in a lower tone, with a glance at the driver, ‘His actual order was, “Go and humour the old bat.”’

They exchanged details of their postings. Bundy confessed he owed his staff job to family connections.

‘I wanted a combat posting. My mother had other ideas.’

His father, Harvey Bundy, was currently a senior adviser in the US War Department under Henry Stimson.

‘So this princess,’ he said. ‘I hear she’s all there.’

‘All there?’ said Rupert.

Bundy curved one hand before his chest.

‘Oh, right,’ said Rupert. ‘I wouldn’t know.’

He had never thought of the seventeen-year-old Princess Elizabeth as a sexual being.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Bundy. ‘I’m not going to wolf-whistle.’

Rupert looked at the passing shopfronts and was silent. Wartime was supposed to change things, break down the barriers. But even when the barriers were down, you had to do it yourself. No one was going to do it for you. There was no one you could talk to about these things. No one in all the world. About feeling ashamed. About wanting it so much.

The car emerged onto the Bayswater Road.

‘I asked round for tips on meeting royalty,’ said Bundy. ‘Apparently you call her ma’am, and you don’t sit until she sits.’

‘Ma’am? The poor girl’s only seventeen.’

‘So what are you going to call her? Liz?’

‘In the family she’s called Lilibet.’

‘How’d you know that?’

‘Mountbatten told me.’

‘Okay. Lilibet it is. Have another slice of pie, Lilibet. Want to take a walk in the shrubbery, Lilibet?’

Rupert glanced nervously at the back of the chauffeur’s head, but he showed no signs that he was listening.

‘Is that what you do with girls?’ said Rupert. ‘Take them into the shrubbery?’

‘I’ll be honest with you,’ said Bundy. ‘I’m no expert.’ He leaned closer and spoke low. ‘When I was twelve years old we went to Paris, and my mother took me to the Folies-Bergère. The way she tells it, I got bored by the naked girls and went outside to read a book.’

‘And did you?’

‘That’s her story.’

The car was now turning into Kensington Palace Gardens. There on the pavement outside the Soviet embassy was a young Russian officer, standing stiffly, almost at attention.

‘Our noble ally,’ said Bundy.

The Russian had a square, serious face and heavy eyebrows. He gazed inscrutably on the open-backed car as it pulled up beside him.

‘You are the party for Lady Astor?’

He sounded exactly like an American.

‘That’s us,’ said Bundy. ‘Jump in.’

He squeezed onto the seat beside them, and the car set off down Notting Hill Gate to Holland Park. His name was Oleg Troyanovsky. His father had been the Soviet Ambassador in Washington before the war, and he had been sent to school at Sidwell Friends. Within minutes he and Bundy had discovered mutual acquaintances.

‘Of course I know the Hayes boys,’ said the Russian. ‘I was on the tennis team with Oliver Hayes.’

‘So what are you doing in London?’

‘Joint committee on psych warfare.’ The wrinkles between

his eyebrows deepened as he spoke. ‘My father arranged it, to keep me away from the eastern front.’

‘Check,’ said Bundy. ‘Privilege knows no boundaries.’

‘And here we are, going to tea with a princess.’

They grinned at each other, bound together by a shared awareness of the absurdity of their situation. The car picked up speed coming out of Hammersmith and onto the Great West Road. The wind blew away their words, and conversation languished. They looked out at the endless line of suburban villas rolling by, and thought their own thoughts.