Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (35 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

By early summer the flats were almost completed, and I knew I would soon be out of a job. There was no prospect of another, but I wasn’t worried; I never felt so beefily strong in my life. I remember standing one morning on the windy roof-top, and looking round at the racing sky, and suddenly realizing that once the job was finished I could go anywhere I liked in the world.

There was nothing to stop me, I would be penniless, free, and could just pack up and walk away. I was a young man whose time coincided with the last years of peace, and so was perhaps luckier than any generation since. Europe at least was wide open, a place of casual frontiers, few questions and almost no travellers.

So where should I go? It was just a question of getting there – France? Italy? Greece? I knew nothing at all about any of them, they were just names with vaguely operatic flavours I knew no languages either, so felt I could arrive new-born wherever I chose to go. Then I remembered that somewhere or other I’d picked up a phrase in Spanish for ‘Will you please give me a glass of water?’and it was probably this rudimentary bit of lifeline that finally made up my mind. I decided I’d go to Spain.

So as soon as I was sacked from the buildings, at the beginning of June, I bought a one-way ticket to Vigo. I remember it cost £4, which left me with a handful of shillings to see me safely into Spain. I didn’t bother to wonder what would happen then, for already I saw myself there, brown as an apostle, walking the white dust roads through the orange groves.

The ship wasn’t due to sail for a couple of weeks, so I spent my last days in London with a girl called Nell, who I’d found in a cinema. She came from Balham, and we used to meet on the Heath and then sometimes go to my room. She was soft and nervous, creamily pretty, buxom, yet plaintively chaste. Intoxicated by idleness – she was out of work too – and by the aura of incipient farewell, she used to lie in my arms in the summer dusk, struggling to save us both from sin. She wore the loose peasant blouse that was the fashion of the day, a panting bundle of creviced cotton, and as our time grew shorter she grew larger and softer as though all her frontiers were melting away. Then our last night came: ‘Perhaps you could tie my hands. Then I couldn’t say nothing, could I?’ Finally: ‘Take me with you. I wouldn’t be any trouble.’ I felt light-headed, detached, and heartless. ‘Take me with you’ was something I was also hearing from other girls, who seemed not to have noticed me till now. For the first time I was learning how much easier it was to leave than to stay behind and love.

The morning came for departure, and the children helped me pack and Mike gave me his pocket jack-knife. Beth had gone off to work, leaving me a note of farewell, and Mrs Flynn was still asleep. Patsy walked half-way to the station with me, and we stopped on Putney Bridge. It was a fine chill morning, with a light mist on the river and the tide running fast to the sea. Patsy stood on tip-toe and grabbed hold of my ear and pulled it down to her paint-smeared mouth. ‘Take me with you,’ she said, then gave a quick snort of laughter, waved goodbye, and ran back home.

It was early and still almost dark when our ship reached the harbour, and when out of the unconscious rocking of sea and sleep I was simultaneously woken and hooked to the coast of Spain by the rattling anchor going over the side.

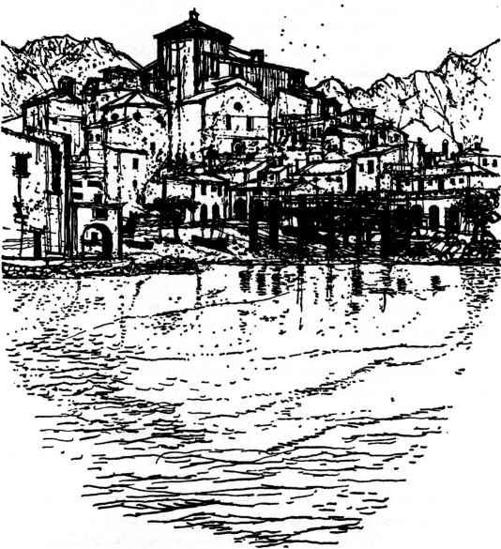

Lying safe in the old ship’s blowsy care, I didn’t want to move at first. I’d enjoyed the two slow days coming down the English Channel and across the Bay of Biscay, smelling the soft Gulf winds blowing in from the Atlantic and feeling the deep easy roll of the ship. But this was Vigo, the name on my ticket, and as far as its protection would take me. So I lay for a while in the anchored silence and listened to the first faint sounds of Spain – a howling dog, the gasping spasms of a donkey, the thin sharp cry of a cockerel. Then I packed and went up on to the shining deck, and the Spanish sun rose too, and for the first time in my life I saw, looped round the bay, the shape of a foreign city.

I’d known nothing till then but the smoother surfaces of England, and Vigo struck me like an apparition. It seemed to rise from the sea like some rust-corroded wreck, as old and bleached as the rocks around it. There was no smoke or movement among the houses. Everything looked barnacled, rotting, and deathly quiet, as though awaiting the return of the Flood. I landed in a town submerged by wet green sunlight and smelling of the waste of the sea. People lay sleeping in doorways, or sprawled on the ground, like bodies washed up by the tide.

But I was in Spain, and the new life beginning. I had a few shillings in my pocket and no return ticket; I had a knapsack, blanket, spare shirt, and a fiddle, and enough words to ask for a glass of water. So the chill of dawn left me and I began to feel better. The drowned men rose from the pavements and stretched their arms, lit cigarettes, and shook the night from their clothes. Bootblacks appeared, banging their brushes together, and strange vivid girls went down the streets, with hair like coils of dripping tar and large mouths, red and savage.

Still a little off balance I looked about me, saw obscure dark eyes and incomprehensible faces, crumbling walls scribbled with mysterious graffiti, an armed policeman sitting on the Town Hall steps, and a photograph of Marx in a barber’s window. Nothing I knew was here, and perhaps there was a moment of panic – anyway I suddenly felt the urge to get moving. So I cut the last cord and changed my shillings for pesetas, bought some bread and fruit, left the seaport behind me and headed straight for the open country.

I spent the rest of the day climbing a steep terraced valley, then camped for the night on a craggy hilltop. Some primitive instinct had forced me to leave the road and climb to this rock tower, which commanded an eagle’s view of the distant harbour and all the hills and lagoons around it. Here, sitting on a stone, about six miles inland, I could look out in all directions, see where I was in the landscape, where I’d been that day, and much of the country still to come. Wild and silent, like a picture of western Ireland, it rolled rhythmically and desolately away, and faced with its alien magnificence I felt a last pang of homesickness, and the first twinge of uneasy excitement.

The Galician night came quickly, the hills turned purple and the valleys flooded with heavy shadow. The jagged coastline below, now dark and glittering, looked like sweepings of broken glass. Vigo was cold and dim, an’unlighted ruin, already smothered in the dead blue dusk. Only the sky and the ocean stayed alive, running with immense streams of flame. Then as the sun went down it seemed to drag the whole sky with it like the shreds of a burning curtain, leaving rags of bright water that went on smoking and smouldering along the estuaries and around the many islands. I saw the small white ship, my last link with home, flare like a taper and die away in the darkness; then I was alone at last, sitting on a hilltop, my teeth chattering as the night wind rose.

I found a rough little hollow out of the wind, a miniature crater among the rocks, ate some bread and dates, unrolled the blanket and wrapped myself inside it. I laid the fiddle beside me, used the knapsack as a pillow, and stretched out on the bed of stones; then folded my hands, hooked my little fingers together, shut my eyes and prepared to sleep.

But I slept little that night: I was attacked by wild dogs – or they may have been Galician wolves. They came slinking and snarling along the ridge of my crater, hackles bristling against the moon, and only by shouting, throwing stones, and flashing my torch in their eyes was I able to keep them at bay. Not till early dawn did they finally leave me and run yelping away down the hillside, when I fell at last into a nightmare doze, feeling their hot yellow teeth in my bones.

When I awoke next morning it was already light, and voices were screaming at one another in the valley. I looked at my watch and it was six o’clock, and I was heavily drenched in dew. I wriggled out of the blanket, crawled on to the ridge and lay in the rising sun, and was met by the resinous smell of drying bushes, peppery herbs, and stones. As I warmed my stiff limbs, I looked down the valley from which the sharp hard cries were coming, and saw a group of old women, as black as charcoal, slapping out sheets along the banks of a stream. Galician peasants, women

and

Spanish, unknown and doubly inscrutable – their thin bent bodies knelt over the water, jerking up and down like drinking hens, and as they worked they shrieked, firing off metallic bursts of speech that bounced off the rocks like bullets.

I lay on my belly, the warm earth against me, and forgot the cold dew and the wolves of the night. I felt it was for this I had come: to wake at dawn on a hillside and look out on a world for which I had no words; to start at the beginning, speechless and without plan, in a place that still had no memories for me.

For as I woke that second morning, with the whole of Spain to walk through, I was in a country of which I knew nothing. The names of Velazquez, Goya, El Greco, Lope de Vega, Juan de la Cruz were unknown to me; I’d never heard of the Cordoban Moors or the Catholic kings; nor of the Alhambra or the Escorial; or that Trafalgar was a Spanish Cape, Gibraltar a Spanish rock, or that it was from here that Columbus had sailed for America. My small country school, always generous with its information as to the exports of Queensland and the fate of Jenkins’s ear, had provided me with nothing more tangible or useful about Spain than that Seville had a barber, and Barcelona nuts.

But I was innocent then of my ignorance, and so untroubled by it. My clothes steamed and dried as the sun grew stronger. The distant sea shone white, a clean morning freshness after last night’s smoky fires. The rising hills before me went stepping away inland, fiercely shaped under the great blue sky. I nibbled some bread and fruit, rolled my things in a bundle, and washed my head and feet in a spring. Then shouldering my burden, and still avoiding the road, I took a track south-east for Zamora.

For three or four days I followed the track through the hills, but saw only occasional signs of life – sometimes a shepherd’s hut, or a distant man walking, or a solitary boy with a flock of goats; otherwise no sound or movement except the eagles overhead and the springs gushing out of the rocks. The track climbed higher into the clear cold air, and I just followed it, hoping to keep direction. When twilight came, I curled up where I was, too exhausted to mind the cold. One night I took shelter in a ruined castle which I found piled on top of a crag – a gaunt roofless fortress tufted with the nests of ravens and scattered with abandoned fires. The skeleton of a sheep stood propped in one corner, picked clean, like a wicker basket; and drawings of women and horses were scratched round the walls. An obvious refuge, I thought, for bandits. But I slept well enough in the tottering place, in spite of its audible darkness, the rustling in the walls, the squeaks and twitters, and the sighing of the mountain wind.

Otherwise all I remember of those first days from Vigo is a deliriously sharpening hunger, an appetite so keen it seemed almost a pity to satisfy it, so voluptuous it was.

By the second day I’d finished my bread and dates, but I found a few wild grapes and ate them green, and also the remains of a patch of beans.

Then I remember coming out of a gorge one early evening and seeing my first real village. I remember it well, because it was like all Spain, and it was also my first encounter. It stood on a bare brown rock in the sinking sun – a pile of squat houses like cubes of pink sugar. In the centre rose a tower from which a great black bell sent out cracked jerking gusts of vibration. I’d had enough of the hills and lying around in wet bracken, and now I smelt fires and a sweet tang of cooking. I climbed the steep road into the village, and black-robed women, standing in doorways, made soft exclamations as I went by.