Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (56 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

Once in the street, my companion glanced quickly at the sky, put out his cigarette, and rolled up his collar. ‘Stay close, and say nothing,’ he muttered briefly, then shot off up a narrow lane. I hurried after him, and we were out of the village immediately, climbing a steep and brutish path. The man raced on ahead of me,taking little goat-like leaps and dodging nimbly from rock to rock. I could see his tall gaunt figure bouncing against the hazy stars. He never bothered to check that I was still behind him.

Easy enough for him, I thought: he was built for these mountains while I’d been raised on very low hills. His legs were long and mine were short – I was also carrying a twenty-pound load. I did my best to keep with him but he soon outstripped me and I started to fall farther and farther back. I wanted to shout, ‘Wait a minute!’ but it didn’t seem to be the thing to do. Instead, I began to indulge in a bit of carefree whistling.

That stopped him in the end. I found him perched on a rock waiting impatiently for me to catch up. ‘Stop whistling,’ he growled. ‘Save it for the other side. This is no time for trivialities.’ At least I was grateful for the halt, and the conversation. I asked him if he did this often. I must be mad, he said; it was the very first time, and by God he was sorry already.

He started climbing again while I went panting behind him, sweat trickling down my arms and legs. Brittle gusts of dry snow swept by on the wind, striking the face like handfuls of rice. I felt engulfed by a contest that was growing too large for me; something I’d asked for but doubted that I could carry through. My companion ignored this, pushing ahead more relentlessly than ever, as though wishing to put me to the final test. That last half-hour was perhaps the worst I’ve known, casually unprepared as I was; ill-shod, badly clothed, and lumbered with junk, clawing my way up these icy slopes.

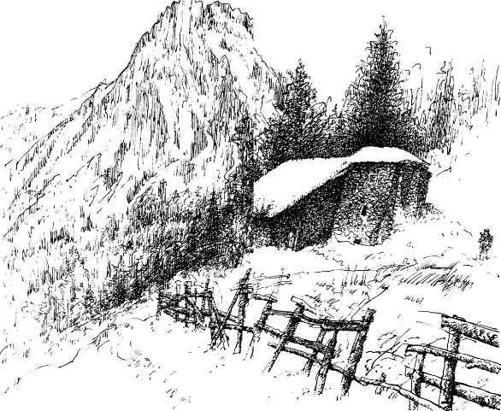

The point of collapse must have been near, but luckily I escaped it, for at last we reached the top of the rise. We were in a narrow pass flanked by slabs of rock which stood metallic and blue in the starlight. I seemed to sense a change in the air, a curious lifting of pressure before me as though some great obstacle had been rolled away. There was also a faint smell of charcoal, woodsmoke, and mules, and an indefinable whiff of pepper. My guide drew me into the shadows and gestured me to silence, sticking out his neck and sniffing the sky. We crouched in the darkness listening. We heard the wind, falling water, and what sounded like a distant gunshot.

‘This is where I leave you,’ said the Frenchman. He appeared a little more cheerful now. ‘The frontier is between those rocks. Follow the path for half a kilometre and you’ll come to a little farm. Knock on the door and you’ll be among your friends.’

Suddenly it seemed too simple – after weeks of speculation and doubt, and these last two exhausting days – just a gap in the rocks a few hundred yards ahead of me, the tiny frontier between peace and war.

‘Move slow and easy. There may be a few guards about but they shouldn’t be too lively on a night like this. If you’re challenged, drop everything and run like hell. Good luck, then; I can do no more.’

But there was no opposition. I just walked towards the rocks and slipped between them as though on an evening stroll. A narrow path led downwards among the boulders. Then, after about half a kilometre, just as the Frenchman had said, I saw a little farmhouse and knocked on the door. It was opened by a young man with a rifle who held up a lantern to my face. I noticed he was wearing the Republican armband.

‘I’ve come to join you,’I said.

‘Pase usted,’ he answered.

I was back in Spain, with a winter of war before me.

Illustrated by Keith Bowen

To the defeated

3. To Albacete and the Clearing House

8. The Frozen Terraces of Teruel

In December 1937 I crossed the Pyrenees from France – two days on foot through the snow. I don’t know why I chose December; it was just one of a number of idiocies I committed at the time. But on the second night, near the frontier, I was guided over the last peak by a shepherd and directed down a path to a small mountain farmhouse.

It was dark when I reached it – a boulder among boulders – and I knocked on the door, which was presently opened by a young man with a rifle. He held up a lantern to my face and studied me closely, and I saw that he was wearing the Republican armband.

‘I’ve come to join you,’ I said.

‘

Pase usted

,’ he answered.

I was back in Spain, with a winter of war before me.

The young man slung his rifle over his shoulder and motioned me to enter the hut. A dark passage led to a smoky room. Inside, in a group, stood an old man and woman, another youth with a gun, and a gaunt little girl about eleven years old. They were huddled together like a family photograph fixing me with glassy teeth-set smiles.

There was a motionless silence while they took me in – seeing a young tattered stranger, coatless and soaked to the knees, carrying a kit-bag from which a violin bow protruded. Suddenly the old woman said ‘Ay!’ and beckoned me to the fire, which was piled high with glowing pine cones.

I crouched, thawing out by the choking fumes, sensing deeply this moment of arrival. I felt it first when threading through the high rocks of the frontier, when, almost by pressures in the atmosphere, and the changes of sound and scent, a great door seemed to close behind me, shutting off entirely the country I’d left; and then, as the southern Pyrenees fell away at my feet, this new one opened, with a rush of raw air, admitting all the scarred differences and immensities of Spain. At my back was the tang of Gauloises and slumberous sauces, scented flesh and opulent farmlands; before me, still ghostly, was all I remembered – the whiff of rags and woodsmoke, the salt of dried fish, sour wine and sickness, stone and thorn, old horses and rotting leather.

‘Will you eat?’ asked the woman.

‘Don’t be mad,’ said her husband.

He cleared part of the table, and the old woman gave me a spoon and a plate. At the other end the little girl was cleaning a gun, frowning, tongue out, as though doing her homework. An old black cooking-pot hung over the smouldering pine cones, from which the woman ladled me out some soup. It was hot, though thin, a watery mystery that might have been the tenth boiling of the bones of a hare. As I ate, my clothes steaming, shivering and warming up, the boys knelt by the doorway, hugging their rifles and watching me. Everybody watched me except for the gun-cleaning girl who was intent on more urgent matters. But I could not, from my appearance, offer much of a threat, save for the mysterious bundle I carried. Even so, the first suspicious silence ended; a light joky whispering seemed to fill the room.

‘What are you?’

‘I’m English.’

‘Ah, yes – he’s English.’

They nodded to each other with grave politeness.

‘And how did you come here perhaps?’

‘I came over the mountain.’

‘Yes, he walked over the mountain… on foot.’

They were all round me at the table now as I ate my soup, all pulling at their eyes and winking, nodding delightedly and repeating everything I said, as though humouring a child just learning to speak.

‘He’s come to join us,’ said one of the youths; and that set them off again, and even the girl lifted her gaunt head and simpered. But I was pleased too, pleased that I managed to get here so easily after two days’ wandering among peaks and blizzards. I was here now with friends. Behind me was peace-engorged France. The people in the kitchen were a people stripped for war – the men smoking beech leaves, the soup reduced to near water; around us hand-grenades hanging on the walls like strings of onions, muskets and cartridge-belts piled in the corner, and open orange-boxes packed with silver bullets like fish. War was still so local then, it was like stepping into another room. And this was what I had come to re-visit. But I was now awash with sleep, hearing the blurred murmuring of voices and feeling the rocks of Spain under my feet. The men’s eyes grew narrower, watching the unexpected stranger, and his lumpy belongings drying by the fire. Then the old woman came and took me by the elbow and led me upstairs and one of the boys followed close behind. I was shown into a small windowless room of bare white-washed stone containing a large iron bed smothered with goatskins. I lay down exhausted, and the old woman put an oil lamp on the floor, placed a cold hand on my brow, and left me with a gruff good-night. The room had no door, just an opening in the wall, and the boy stretched himself languidly across the threshold. He lay on his side, his chin resting on the stock of his gun, watching me with large black unblinking eyes. As I slipped into sleep I remembered I had left all my baggage downstairs; but it didn’t seem to matter now.