Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (60 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

Eulalia, with her beautiful neck and shoulders, also had a quiet dignity and grace. A wantonness, too, so sudden and unexpected, I felt it was a wantonness given against her will. Or at least, if not given willingly, it was now part of her nature, the result of imposed habit and tutoring.

As she pulled on her tattered slippers, she told me she would not stay long in Figueras. She’d come from the south, she said – she didn’t know where – and had been working here as a house-drudge since she was ten. Once she would have stayed on till body and mind were used up; the sexually abused slattern of some aged employer, sleeping under the stairs between calls to his room. Not any more, she was now free to do as she wished. Spain had changed, and the new country had braver uses for girls such as she. She need stay no longer with this brutal pig of an innkeeper. She would go to Madrid and be a soldier.

It had grown dark and cold in the cellar. Suddenly she turned and embraced me, wrapping me urgently in her hot thin arms.

‘Frenchman!’ she whispered. ‘At last I have found my brother.’

‘Englishman,’ I said, as she slipped away.

The next morning there was an outbreak of discipline in the barracks. Soon after daylight, scattered committees, in groups, began to gather in the courtyard. The Commandant – who was he? – strode about in mottled riding-boots and a cape, greeting us with uneasy bonhomie.

By majority vote it was agreed we should have some exercise and drill. Somebody blew on a bugle. Men sauntered out on to the parade-ground and arranged themselves in rows. Others ran away, thinking the bugle meant retreat or an air-raid.

Those who were left then marched up and down, shouting orders at each other, forming threes and fours, running at the double, falling over, falling out, standing still, arguing, and finally parading past the Commandant from several directions, while he stood on a chair saluting.

We were an uneven lot; large and small, mostly young, hollow-cheeked, ragged, pale, the sons of depressed and uneasy Europe. But confused as we were as we marched about, there seemed to be a growing urgency in our eyes. We were fumbling to find some order of courage; and there was that moment when we almost came together in line and step, and as we swept past the Commandant once again, our clenched fists raised, we felt that bursting of the chest and tightening of the throat which made heroes and warriors of us all. Even the Czechs and Russians seemed to be briefly affected and smiled faintly at one another.

That afternoon, having declared our brotherhood of purpose, we held a mass meeting in the mess shed to study the tactics of war. Several groups sat round tables shuffling dominoes into lines of battle. A military exercise was proposed, seconded and forgotten. A Russian drew arrows in charcoal on a white-washed wall – all centred on Figueras and pointing eastward, and home.

Doug swept in and out of the shed wearing a new leather jacket and leading a small Frenchman in a Verdun helmet. I sensed an air of busy intention and high resolve around me, and for the first time since I arrived heard strength in men’s voices.

“Aven’t they told ye?’ barked Doug, briskly halting at my table, his thick Scots overlaid with Military Academy cadences. ‘They’re putting on a show this afternoon. Parade at 14.00 hours sharp. And get into some decent uniform, you soft English lemon.’

We gathered in the square, blowing in the ice-sharp wind, and were given long sticks for guns. We were going to attack a ‘strong point’ up the hill, an enemy machine-gun position; a frontal and flanking assault on bare rising ground. ‘The attack will be pushed home with surprise and determination,’ said the Commandant. ‘It happens all the time.’

We jogged up and down, playing football with stones, changing our platoons at will. Then, after rival shouts of command, of which we obeyed the loudest, we were over the wall and up the rocky hill. We could hear the machine-guns stuttering away at the top of the rise – rusty oil-drums being beaten with sticks.

Half-way up, we halted. ‘Well, attack!’ said someone. We stood undecided, not knowing what to do. Then a fellow ahead of us threw himself face down on the ground, and began to wriggle forward and upward on his belly. So we all did the same, and it was fun for a moment – but we very soon changed our minds. As a method of progress it was slow, uncomfortable, dirty and boring. Some of us swore; I heard a man say, ‘Sod this for a lark.’ So a few of us got to our feet and started walking again. The oil-drums were still rattling away up ahead, and we were sauntering up the hill in front. Almost invisible among the rocks, his bottom high in the air, Doug was shouting, ‘Get yer ‘eads down, you stoopid buggers!’ Away in the distance, to the left and right of us, straggling lines of other chaps wriggled up the hill. It looked almost realistic, so I dropped into position again, crawling and following another man’s boots.

Near the top of the hill, with the banging of the oil-drums much closer, our leaders cried, ‘Forward! Adelante! Charge!’ We leapt to our feet and galloped the last few yards, shouting as horribly as we could, and cast ourselves on the men who had been beating the oil-drums, who then threw up their arms and surrendered, sniggering.

Twenty minutes’ crawling and sauntering up that bare open hill, and we had captured a machine-gun post, without loss. Our shouting died; it had been a famous victory. Real guns would have done for the lot of us.

We finished the day’s training with an elaborate anti-tank exercise. A man covered a pram with an oil-cloth and pushed it round and round the square, while we stood in doorways and threw bottles and bricks at it. The man pushing the pram was Danny, from London. He was cross when a bottle hit him.

The next day, in the evening, a child brought me a message, and as soon as I was free I slipped down to the town. This time I went alone, but not immediately to Josepe’s, but first to an old wine bar up near the Plaza. The first man I saw was the giraffe-necked Frenchman from the Pyrenees who had guided me over the last peak of the mountains. He’d been taciturn, gruff. ‘Don’t do this for everyone,’ he’d said. ‘Don’t think we run conducted tours.’ Which was exactly what he was doing, as I could see now. Beret and leather jacket, long neck still lagged with a scarf, he stood in the centre of the bar talking to a group of hatless young men, each looking slightly bewildered and carrying little packages. Smoking with rapid puffs, eyes shifting and watchful, marshalling his charges with special care, he handed each one a French cigarette, then pushed them towards the door. His coat was new, and his shoes well polished, and clearly he had walked no mountain paths lately. Perhaps he’d brought this little group across the frontier by truck. As he left the room, he brushed against me, caught my eye for a moment and winked…

I went down the street in the freezing rain and found Felipe’s bar closed and dark. Through a crack in the shutters I could see a glimmer of candles and some old women sitting by a black wooden box. Bunches of crape hung over the mirror behind the bar which was littered with broken bottles. I was wondering why, and from whom, the message had been sent up to the barracks. It had certainly been laconic enough. The boy had simply sidled in and asked me if I was ‘Lorenzo the Frenchman’, and then muttered, ‘You’ve got to go down to Felipe’s.’

I knocked on the door and presently one of the old women let me in. She asked who I was and I told her. ‘Where’s Don Felipe?’ I said, and she showed her gums briefly, then said, ‘Bang! He’s gone to the angels.’ She stabbed a finger at the open box, and there he was, his face black and shining like a piece of coal. ‘Bang!’ said the old woman again, with a titter, then crossed herself. ‘God forgive him.’

Where was Eulalia? I asked. ‘She went in a camion,’ she said. ‘An hour ago. Away over there…’ I could get no more from her, except that the old man had been shot and that, in her opinion, he was without shame and deserved it.

Looking into the crone’s bright death-excited eyes, and smelling the hot pork-fat of the candles, I knew that this was not a wake, or even a mourning, but a celebration of something cleared from their lives. I also knew that Eulalia, my murderous little dancer, had called me to show me what she’d done, but called me too late, and had gone.

House

Ten days after my arrival at Figueras Castle enough volunteers had gathered to make up a convoy. By that time we were sleeping all over the place – in tents in the courtyard, under the mess-hall tables, or the lucky ones in the straw-filled dungeons. Day after day, more groups of newcomers appeared – ill-clad, crop-haired and sunken-cheeked, they were (as I was) part of the skimmed-milk of the middle-Thirties. You could pick out the British by their nervous jerking heads, native air of suspicion, and constant stream of self-effacing jokes. These, again could be divided up into the ex-convicts, the alcoholics, the wizened miners, dockers, noisy politicos and dreamy undergraduates busy scribbling manifestos and notes to their boyfriends.

We were collected now to be taken to where the war was, or, at least, another step nearer. But what had brought us here, anyway? My reasons seemed simple enough, in spite of certain confusions. But so then were those of most of the others – failure, poverty, debt, the law, betrayal by wives or lovers – most of the usual things that sent one to foreign wars. But in our case, I believe, we shared something else, unique to us at that time – the chance to make one grand, uncomplicated gesture of personal sacrifice and faith which might never occur again. Certainly, it was the last time this century that a generation had such an opportunity before the fog of nationalism and mass-slaughter closed in.

Few of us yet knew that we had come to a war of antique muskets and jamming machine-guns, to be led by brave but bewildered amateurs. But for the moment there were no half-truths or hesitations, we had found a new freedom, almost a new morality, and discovered a new Satan – Fascism.

Not that much of this was openly discussed among us, in spite of our long hours of idle chatter. Apart from the occasional pro-nunciamentos of the middle-Europeans, and the undergraduates’ stumbling dialectics, I remember only one outright declaration of direct concern – scribbled in charcoal on a latrine wall:

The Fashish Bastids murdered my buddy at Huesca.

Don’t worry, pal. I’ve come to get them.

(Signed) HARRY.

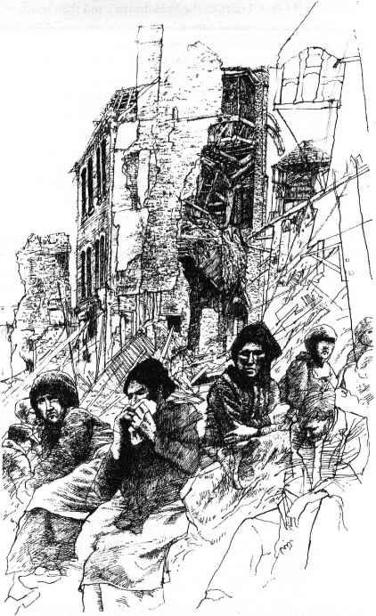

The morning came for us to leave. But it wouldn’t be by camiones after all. The snow was too heavy. We would go by train. After a brief, ragged parade, and when we had formed into lines of three, the Commandant suddenly appeared with my baggage. ‘It’s all there,’ he said, strapping it on to my shoulders, ‘all except the camera, that is.’ He gave me a sour, tired look. ‘We don’t ever expect much from you, comrade. But don’t ever forget – we’ll be keeping our eye on you.’

The Castle gates were thrown open, sagging loose on their hinges, and in two broken columns we shuffled down to the station. A keen, gritty snow blew over the town, through the streets, and into our faces. We passed Josepe’s, whose windows were now boarded up and outside which an armed militiaman huddled. On the station platform a group of old women, young girls, and a few small boys had gathered to see us off. A sombre, Dore-like scene with which I was to become familiar – the old women in black, watching with watery eyes, speechless, like guardians of the dead; the girls holding out small shrunken oranges as their most precious offerings; the boys stiff and serious, with their clenched fists raised. The station was a heavy monochrome of black clothes and old iron, lightened here and there by clouds of wintry steam. An early Victorian train stood waiting, each carriage about the size of a stage-coach, with tiny windows and wooden seats. Every man had a hunk of grey bread and a screwed-paper of olives, and with these rations we scrambled aboard.