Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (64 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

At last they sorted out a bunch of the greenest among us and put us in open lorries for Tarazona de la Mancha. This was the training camp for the 15th Brigade and lay some thirty miles across the plain to the north. It was the next leisured step in our preparation as fighting-men. Not one of us had fired a rifle, nor even held one as yet, but in Tarazona, they said, this would be seen to.

A half a dozen trucks took us over the frozen stream at La Gineta and humped us across the plateau. Sunlight blazed from the snow like an arctic summer, and blank umbrella pines stood darkly about. For once there was no wind, and although the air was freezing, we sang our way into the waiting town.

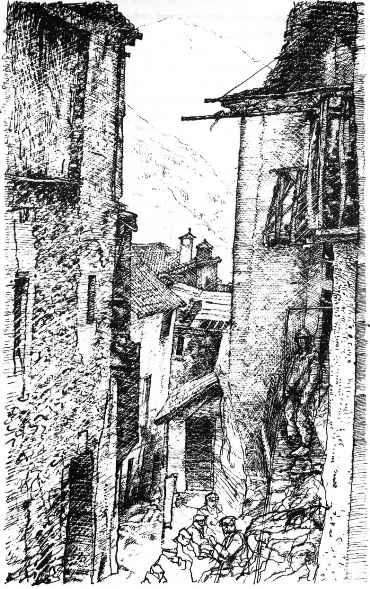

When we arrived we stopped singing. Tarazona de la Mancha looked hard and grim, a piece of rusted Castilian iron. The poverty of the snow-daubed hovels, huddled round the slushy square, gave an appearance of almost Siberian dejection. Squat, padded figures crept slowly about, each wrapped in a separate cocoon; and the harsh silence of the place and the people seemed to be sharing one purposeless imprisonment, where nothing soft, warm, tender or charitable could be looked for any more. This was a Spain stretched dead on a slab, a frozen cadaver, where, for all our early enthusiasms, we seemed to have come too late, not as defenders but as midnight scavengers.

Certainly Albacete had been shambles enough, but I remember the glazed astonishment in the eyes of my mates as we jumped off the lorries and gaped round the apparently empty and war-scalloped square. We were, in our forebodings, only half right; it seemed there was still some military life left in the town – up and down side-streets, in and out of the houses, soldiers came and went in ones and twos as though conducting some complicated domestic manoeuvres. Each was dressed in flamboyant rags which seemed to have designed themselves. Others carried baskets of potatoes, or bundles of wood, others broken pieces of furniture.

Some voice of authority we hadn’t known we’d brought with us suddenly bawled at us to stand in line. An odd figure appeared, as though from a hole in the ground, said he was the Political Commissar, and addressed us briefly. I remember him well because, in spite of the cold, he was wearing only his pyjamas under a tattered poncho. He said we’d come at the right moment, that victory was just round the corner, in our grasp, awaiting one final effort based on our ideological discipline. As he spoke he kept jumping up and down holding himself, like a little boy bursting to go to the lavatory. The man wore ragged odd slippers, and his toes were bare.

That was our welcome. We were then marched to our barracks, a back-street warehouse with ragged holes in the roof. We were stamped, listed, numbered, named, and each given a mint-new hundred peseta note. I looked at it in wonder, recalling my earlier days in this country, when five pesetas would last me the best part of a week. I stroked this finely engraved and watermarked piece of paper and thought of the princely excesses it might so recently have bought me. Wandering out through the town to see what the shops had to offer, I found only one, and it was selling beech nuts.

The central square in Tarazona must once have had some rough rusting elegance, but it was now badly battered by the fact of war. There’d been no fighting here, but the withdrawal of all normal life, together with a sudden revulsion for the past, had left their sickly marks everywhere. Chief sufferer, of course, was the ancient church, whose high-roofed edifice, hacked from red stone, now grimly haunted the plaza. The outside looked blind, blank and faceless, but the inside was now bare as a barn – the walls and little chapels cleared of their stars and images, the altar stripped, all the vestments gone. I couldn’t help being reminded of our own Civil War, and of Cromwell’s followers hatcheting the faces of the old stone saints, and stabling their horses in churches.

Now the inside of Tarazona’s own church had an almost medieval mystery and bustle, an absence of holy silences and tinkling rituals, and a robust and profane reoccupation by the people. I found soldiers sleeping by the walls, under slashed and defaced icons, or sitting round flaming wood fires whose smoke drifted in clouds of shafted sunlight up to the smashed stained-glass windows under the roof. Here were arguments, singing, the perpetual boiling of water in cans, curses of men stumbling over sleeping figures, the high jangling of bells rung for sport or mischief, the sudden animal shriek of female laughter.

All over Republican Spain now such churches as this – which had stood for so long as fortresses of faith commanding even the poorest of villages, dominating the black-clad peasants and disciplining their lives and souls with fearsome liturgies, with wax-teared Madonnas and tortured Christs, tinselled saints and gilded visions of heaven – almost all were being taken over, emptied, torn bare, defused of their mysteries and powers, and turned into buildings of quite ordinary use, into places of common gathering.

But in this particular occupation of Tarazona’s main church, I noticed something else. The soldiers who made free with these once holy spaces were a little more than normally loud and hearty, whereas the local villagers, who had perhaps regularly heard Mass here and spoken their darkest secrets in confession, now showed half-timid, half-shocked at what they were doing, and broke out at times into short bursts of hysteria like unchecked children amazed at their wantonness.

We spent the first evening mulling wine over a fire, anything to kill the taste. There was Doug, Danny and Brooklyn Ben, who had miraculously reappeared after his back-street mugging,cleansed of both bruising and political suspicion. Also Sasha, a towering White Russian from Paris and a newcomer to our company.

Danny had found some dried sausage which we fried on sticks. Huge shadows moved over the high arched ceilings, and flickered and died along the walls. We were uneasy; we still hadn’t got used to the way of the village, to its almost brutal casualness and gloom. We didn’t know yet what we were preparing for, or what was being prepared for us. As we drank the hot sour wine Sasha recited some poems of Mayakovsky, and Ben said they sounded better in Yiddish. While they quarrelled, Danny sang some old music-hall songs in a cheerless adenoidal whine, till Doug covered his head with a blanket.

At last we left the Goyescan fires and smoke and half light of the church and went back to the freezing barracks. The guards sat hunched in the gateway, wrapped in balaclavas and ponchos, the late moon glinting on their bayonets. They didn’t seem to care whether we were Moors or infidels. They merely burrowed down into the cold like dogs.

The barrack floor seemed to be covered with sleeping men, but we found a free space in the corner.

‘By the way,’ said Doug, as he settled down in the straw, ‘I saw that lassie of yours today. You know, that wee one from Figueras. The one that kilt her father – or was it her grandfather? Aye, I dunno, but I just saw her riding down the street with a Captain.’

Before light next morning, I was awakened by the sound of a bugle – a sound pure and cold, slender as an icicle, coming from the winter dark outside. In spite of our heavy sleep and grunting longing for more, some of us began to love that awakening, the crystal range of the notes stroking the dawn’s silence and raising one up like a spirit. There were certainly those who cursed the little bleeder, but the Brigade was proud of its bugler; he was no brash, brassy, spit-or-miss blaster of slumber, but one who pitched his notes carefully to the freezing stars and drew them out like threads of Venetian glass.

I got to know about him later. He was not exactly a soldier but a thirteen-year-old choirboy from Cuenca. Our Commander had heard him, kidnapped him, destroyed his papers of identity, and brought him as a pampered prisoner to Tarazona. One sometimes saw him by day, pretty as a doll, wriggling past in his outsize uniform. I spoke to him once, but he answered me in church Latin, eager to be left alone. Indeed, he seemed always to be alone, squirming quickly down side-streets or hurrying out to hide in the fields. It was only in the dark of dawn or at lights out, when he stood unseen at his post, that he was able to send out his frail and tenuous alarms.

After reveille came the brief luxury of lying awake, while those whose turn it was to do so brought round tin-drums of coffee brewed on fires in the snow outside. Ladled into our mugs, it had two cosy qualities: colour and warmth. Its flavour was boiler grease.

Terry, the company leader, a short, round, forty-year-old ex-NCO from Swansea, began his shouting around 6.30 a.m. He had learned an extraordinary, belligerent parade-ground patter which he kept going in an abstract blood-curdling way even when there was no one left in the room.

The company formed up in threes in the icy lane outside, the big chaps in the front, the midgets hidden in the rear, rather like a display on a greengrocer’s stall; then, after much shuffling, we marched off to the plaza.

The morning parade was the only time when our sad little village hardened and seemed to show some purpose and strength. It was then that all the men of the battalion came together from their various nooks and grottoes, and stood under the red-streaked morning sky before our neat and diminutive Commander.

The lines of men were not noticeably impressive, except that we displayed perhaps ,a harmonious gathering of oddities and a shared heroic daftness. Did we know, as we stood there, our clenched fists raised high, our torn coats flapping in the wind, and scarcely a gun between three of us, that we had ranged against us the rising military power of Europe, the soft evasions of our friends, and the deadly cynicism of Russia? No, we didn’t. Though we may have looked at that time, in our wantonly tattered uniforms, more like prisoners of war than a crusading army, we were convinced that we possessed an invincible armament of spirit, and that in the eyes of the world, and the angels, we were on the right side of this struggle. We had yet to learn that sheer idealism never stopped a tank.

After parade came training in the snow – little fat figures running and skipping about the fields, everyone padded up with cloaks and scarves like medieval images from Brueghel. This medievalism spread to the streets where off-duty soldiers sat round interminable wood-fires, or scampered about like children, making slides and playing snowball.

Doug, Sasha and I were drawn aside by the company leader and given a Maxim gun. We were told to take it apart, clean it, put it together, fire it, and generally get used to the thing. He thought we would make a team; I don’t know why. In an icebox cellar beneath the church, Doug and I took the gun to pieces and Sasha reassembled it. First, second and third time of firing, the Maxim jammed. The giant Sasha cursed. Then Doug put it together, and it fired. ‘Sodding Russian,’ he said, but Sasha was in no way put out; he embraced Doug and gave him a screw of tobacco.

That night we queued in the snow for food. The day had been a hard one, and the food was late. We sang and chanted in the lane outside the canteen, banging our spoons and forks on our plates. The food, when it came, was the usual heap of gritty beans mixed with knobby pieces of livid meat. But there were no complaints; we were eating donkey, and we were eating better than most.

Then, I remember, a few days after coming to Tarazona, we got an early morning call for a Special Occasion. The bugles started about 5 a.m. There was a lot of shouting from Terry, and a certain excitement was transmitted. It was suggested we smarten ourselves up a bit, even shave for a change. A sack of new foragecaps, with tassels, were handed around, but after trying them on most of us threw them away.

They marched us, not to the parade-ground, but to the dark interior of the church and lined us up facing a platform half-obscuring the altar. We stood in wet, steaming rows, stamping our feet, and coughing. Electric light-bulbs were switched on, and tension mounted, while we glowered at the empty platform and grumbled.

Suddenly a little man jumped on to it, bouncy as a bull-calf, a minotaur in a short hairy coat, with a shiny half-bald head and piercing dark eyes under heavy commanding eyebrows.

‘Comrades!’ he cried. ‘It is a special honour for me to stand before you at last – heroic defenders of democracy, champion fighters against the Fascist hordes…’ It was Harry Pollitt, leader of the British Communist Party.

Where had he come from, I wondered, and what was he doing here at this hour? Dressed as it were for his King Street office, London, but standing before dawn by a church altar in La Mancha, for half an hour he held us in the grip of his fast, fist-jabbing oratory till he had us all standing with our arms raised, cheering. Pollitt had the true gift of a political leader of being able to rouse a cold and sullen mob, at six-thirty in the morning, by spraying them with short sharp bursts of provoking rhetoric till everyone was howling for victory. Pollitt’s was a spare fighting style, calling us to fresh blood sacrifices, mass-solidarity, and other militant jousts of that order; but even his cliches were honed down to projectiles and pebbles for heroic slings.