Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (63 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

Close to, I could see the long lines of disease running down his beautiful face, and a precocious hardness in his sleepy eyes. He reached me brandy and helped me to drink it; he was cold, but did his wriggling best to warm me. He kept crying my name, and sobbing farewell, and weeping theatrically as the night wore on. I had a feeling he was collecting relationships with the last moments of the condemned. He certainly seemed cheerful enough when he left in the morning. He asked me for my wrist-watch and I gave it to him.

The morning was a muddled embarrassment, without the dramatic clean sweep I’d expected and made myself ready for. Anything that followed now was bound to be fumbled, hurried and probably abominable. Things started at midday. Sam brought me a couple of cigars and a letter addressed to me care of the Socorro Rojo.

‘I wasn’t sure whether you’d want to have this,’ he said, handing me a bulging envelope, already slashed open, and visibly crammed with sheaves of the girl’s voluptuous handwriting. ‘Then I thought, hell, why not? – shows she’s thinking of you, anyway.

Sent you five English pounds, too. Rather a pity about that…’

On his smooth face was that expression of guilty exasperation again. But he wasn’t looking at me.

‘I’ll take your letters,’ he said, and stuffed them in his pocket. He didn’t say goodbye.

That afternoon a doctor visited me and gave me an injection and a couple of pills. Tomasina padded in and out, saying nothing, but giving me shy false smiles as though flicking my face with a handkerchief. I sat at the table drowsing through my girl’s extravagant letters and inhaling their heady unforgivable magic.

About four o’clock I was handcuffed and taken under guard to a room where several militiamen were playing dominoes. They got up when I entered, and went away whistling. Through the door they left open I could see a small courtyard, and snow falling from a sunset sky.

One of the guards gave me a cigarette, the other touched my arm. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘It’s easy, brother.’ Patches of sweat showed through his light blue shirt. Then I heard a murmuring of voices in the next room, subdued salutations and greetings; a sliding panel in the wall was suddenly pushed back. Faces peered at me briskly, one by one – the two Russians, each with a brief nod of the head, an unknown officer in a fur-collared coat, then, framed like some fake Van Gogh freakishly elongated, appeared the unmistakable face of the giraffe-necked Frenchman who had guided me the last few steps across the mountain frontier. One look at me and he covered his eyes in mock horror.

‘Oh, no!’ he groaned, ‘not him again, please. Turn him loose – for the love of heaven.’

He seemed to find the sight of me – manacled and doomed in Albacete’s death row – more diverting than anything else. He turned and spoke rapidly to his companions in the other room, and I heard his high-pitched Gallic cackle. A few orders were given, my handcuffs unlocked, and I was told to get back to the barracks. The two Russians, Tomasina, the girl, the boy, the long shivering night and day of preparation were over. Suddenly, inexplicably free again, I realized that a word from the little French guide showed him to have more power than anyone else around.

Crossing the square in the red twilight, on my way to the barracks, I met Sam striding in the opposite direction. Without a word of greeting or even a glance of recognition, he thrust into my hand the packet of farewell letters I’d written.

Restored to the ranks and the semi-liberty of a lax routine, I began meeting with veterans and took on some of their swagger. Albacete, the base camp of the 15th Brigade, was also a rest camp and clearing centre. I had arrived in Spain in a state of blank ignorance, but soon learned the realities of the times. After the atrocious battles of the late summer, particularly on the Aragon front, there was now a slight lull in the fighting. The Republican Army was left holding about a third of the country, backed by the entire east coast running from the Pyrenees to Almeria. Facing Franco, the line was a loose bellying north-south zig-zag containing a vulnerable bulge driven by the General’s forces. It was true we had a weak salient reaching towards Portugal in the west, but sweeping in a great curve to the north-east Franco held Teruel in the mountains, only fifty miles from the sea, and threatened to cut the Republican territory in half.

Perilous as the situation may have been, it was a time of crazy optimism, too, and all the talk was of an offensive already mounted to recapture Teruel. Troops were even now moving up the freezing heights to surround the city. It would be an Olympian battle to turn the war.

So far it was an affair of Spanish troops only, some suggesting our leaders wished them to be first with the glory. So the International Brigades ‘rested’, in and around Albacete – patching their battered weapons, reshuffling their battalions, feeling pretty certain they would be called on soon.

Meanwhile we newcomers and the veterans massed in the town’s damp cafes, drinking acorn coffee and rolling cigarettes made from dried oak leaves and mountain herbs. Paying for our drinks with special printed money, little cards stamped with the arms of the city. And eating beech nuts roasted on griddles. For a military base camp there was little formal discipline, though to keep warm we sometimes drilled or paraded through the streets, taking the salute of our Commanders, who stood on upturned wine barrels in the driving sleet, looking exhausted, faintly amused, or bored.

I half-remember the shades and styles of some of these still – Cunningham, Ryan, Paddy O’Daire – black-bereted, black-mackintoshed, tight-belted figures; they were the obscure foreshadowers of coming events, the unofficial outriders of imminent World War, and had already learned more of what its wasting realities would be than any fuzz-brained Field Marshal in the armies of Britain or France.

Fred Copeman was another lion of this breed – veteran of Brunete, and once my strike leader when I was a builder’s labourer in Putney. Here in Spain I saw again that hard, hungry face, even more shrunken now by battle and fatigue than by his struggles back home in the early Thirties. When he recognized me his hard eyes glittered with frosty warmth for a moment. ‘The poet from the buildings,’ he said. ‘Never thought you’d make it.’ Stoker Copeman was well known for his part in the naval mutiny of Invergordon, Scapa Flow; a rough-cut, hollow-cheeked, working-class revolutionary, and archetype of all the Commanders of the British Battalion, he was to survive the worst slaughter of the war, which was to bury so many like him, and was later to become, after his return to England, Chief Adviser, Civil Defence, to the Metropolitan Borough of Westminster.

Beneath the speculative, often cynical, regard of such as these, we volunteers, our morale mysteriously rising, marched round Albacete shouting new-learned slogans in pigeon Spanish: ‘Oo-achaypay! No pasaran! Muera las Fascistas! Salud!’

Bullets were in our mouths if not in our rifles. Indeed, few of us had guns at all. We marched to make a noise, to keep warm, to know that we were still alive, our right arms raised high, punching the freezing air, our clenched fists closing on nothing.

I’d been received back into the barracks with some suspicion at first, and I can’t say I was that surprised. You didn’t get picked off the parade-ground, marched under guard to the ‘dispatch house’, interrogated for three days, given Tomasina’s ‘last rites’, only to be suddenly turned free, with all your equipment intact – books, diary, violin – without questions or explanations. It was thought, quite naturally, that I’d been planted among them, and was therefore someone to be avoided.

As Danny, my weedy Cockney friend from Figueras, was quick to point out: ‘We all bin worryin’ abaht you, son. Still are, if you get me.’ He pulled his nose with a sleazy giggle. ‘When ‘telligence blokes get ‘old of summick, they don’t normly let go of it. We reckon you bin lucky, or sumpen, aincha?’

‘Just a small mistake,’ I muttered, and Danny nodded: ‘That’s what I said, then, din’ I?’ For several days I was watched closely, or treated with loud, false camaraderie. Then the news got round that ‘M. Giraffe’, whom they all knew, had vouched for me; also that a mysterious high voice of authority in Madrid had sent a favourable word. I understood the one, but not the other. But this seemed good enough for most of them, anyway.

It was cold. We played cards. Meals were of semi-liquid corned beef, or sometimes something worse, with black frozen potatoes and beans. It was an idle time, still a time of waiting: there were arguments, flare-ups, sudden lunging fights, and dreamy liaisons in barrack-room corners. Brooklyn Ben held political classes, which were often crowded, and which painted a world free from betrayal and butchery. Speaking in his quiet, cracked voice, with its soft Jewish accent, he plumped up the dry demands of Communist dialectic into a nourishing picnic of idealism and love.

Sitting cross-legged on his bed, his forage-cap crammed on his ears, his large eyes melting with warm, brown-sugary sweetness, his message could have been a perversion in the middle of a war, but one which both veterans and newcomers – those who had seen death or sniffed the nearness of it – felt somehow the need to hear. Strangely enough, he was the only one I met who had a good word for the Fascists, calling them ‘ice-cream-lolly boys’ or ‘kindergarten cut-throats’. His classes, advertised on the notice-board and presumably official, were crowded by old lags and new arrivals alike. After about a week, he disappeared. I heard he’d been clubbed in a side-street and carried away. ‘Pro-Fascist nark,’ said someone.

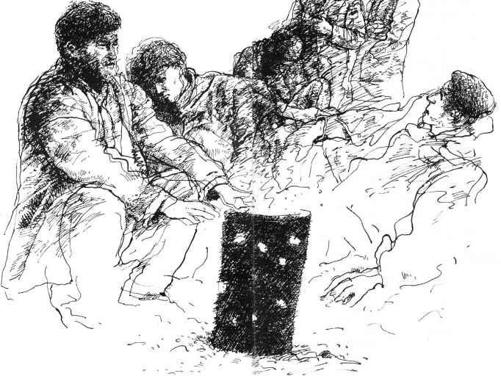

Many of us were now sleeping on the barrack floor, using muddy pallets of straw as mattresses. It was so cold, we were burning the army beds – breaking them at first accidentally. We fed the wood into a punched oil-drum and sat round it at night, ponchos over our shoulders. There was Doug and Danny, Guasch when we could stand him, a skeletal Swede, and a Yank with crutches – one of those legendary few who could charge a cigarette paper with tobacco, roll it, lick it, seal it and light it, and all with a single flick of one hand.

The Yank and the Swede, sculpted by flames from the fire, were scarred by something we could not know. The eyeballs of each seemed to sit easily in the face, but were almost detached, ringed by deep, luminous hollows. There was a look of exhausted madness in the features of both, backed by a languid bitterness of speech.

They were both veterans of the Aragon offensive. The Yank said he hoped the British were sending out less rubbish. The Swede said he didn’t care what they sent so long as he could now go home. While saying this, he rocked gently to and fro, as though riding in a bus on a country road.

‘You won’t get home,’ said the Yank. ‘You still got your legs – the Army can use you yet.’

He quickly rolled him a cigarette and held it to his mouth. The Swede licked it, then sucked and gasped.

The Aragon was a cock-up, the Yank said. No artillery, no planes, no timing, no leaders, everybody running around like rabbits. He was a machine-gu’ ner, had a beautiful Dichterer, too – only they gave him the wrong ammunition. That’s why he had his ass shot off. Lucky to be alive. None of his pals were left.

They were guarding a hill near Belchite, when the Fascists counter-attacked. They were surrounded; couldn’t shoot or run. Some Moors took his pals prisoner, and cut their throats, one by one; then they dropped him off a bridge and broke his legs. He lay for two days, semi-conscious, then dragged himself to the road. The front had shifted, and he was picked up by a battalion bread-van.

He told the story in gritty, throwaway lines – quietly savage, but with no dramatics. ‘We were set up, goddam it. Lambs for the slaughter. No pasaran! They pasaranned all over us.’ He described with light affectation the Spanish officer who had supervised the throat-cutting, the blood on his shirt and his pansy white hands.

‘And d’you know what they gave me when I got back?’ he said. ‘A kind of welcome home, 1 guess.’ He slowly shifted his crutches, unhooked something from his belt, and passed it to me in silence. It was one of those murderous, deep-bladed Albacete clasp-knives, for centuries a sinister speciality of this town. I prised the blade open from its sheath of horn, and the steel flushed red from the fire. Its glowing length was engraved in antique letters:

No me saques sin razon

no me entres sin honor…

‘Don’t open without reason or close without honour,’ said the Yank solemnly.