Russell - A Very Short Indroduction (19 page)

Accordingly, the project of

Principia

, and Russell’s attempts to overcome the technical difficulties in the way of carrying it out, are valuable chiefly because of their ‘spin-offs’ for philosophy rather than for their place in the history of mathematics. The same is true of the work of Frege, except that some of his technical innovations in the formalities of logic were immensely important for its subsequent development.

Frege is the other great thinker at the beginning of the twentieth century who is credited with founding analytic philosophy. The scholar who puts Frege at the centre of the century’s philosophical map, Michael Dummett, argues that the essence of analytic philosophy is the claim that in order to understand how we think about the world, we must examine language, because language is our only route to thought. This makes the philosophy of language central, displacing the theory of knowledge which, since at least Descartes’s time, had held this position. And this displacement of theory of knowledge by philosophy of language owes itself, says Dummett, to Frege. Frege had embarked on the same programme as Russell – beginning two decades earlier – of basing mathematics on logic. He found the logical tools available to him hopelessly inadequate for the task. So he set about inventing new ones, and succeeded. His innovations both simplified logic and greatly extended its power. But he also saw that he would have to example notions of reference, truth, and meaning to carry out his project, and this, says Dummett is where a turn to the philosophy of language began.

Without question Frege’s work is of the first importance in philosophy. It is also without question that Frege influenced Russell, although in the equivocal way sketched a few paragraphs above. But it is hard to agree with Dummett’s claim of historical priority for Frege – and not just because Dummett’s conception of analytic philosophy is unrealistically restrictive. The fact is that Frege’s work was very little known during his own lifetime (he died in 1925), and Russell was almost alone in trying to bring it to wider notice. Even then, it was not until the 1950s – and really not until the first of Dummett’s major studies of Frege in the 1960s – that the full import of his work was appreciated. On the purely historical question it would be more correct to say that the outstanding value of Frege’s ideas is a function of their theoretical rather than their historical importance. For quite a lot of Russell’s work – his theories of perception and knowledge, his philosophies of mind and science – it would be fair to say that the reverse is true: theft importance is historical rather than theoretical. But some of Russell’s work, as we have seen, combines both theoretical and historical value, and that is why it is seminal for analytic philosophy.

The claims of G. E. Moore to a founding role in analytic philosophy are also sometimes advanced, and not without cause. Russell, in his generous way, attributed his emergence from idealism to the influence of Moore, and there is no doubt that Moore’s philosophical temperament and methods had an effect on him. Moore claimed that whereas most philosophers began to philosophize because of wonder, his reason for doing so was that he found what other philosophers said astonishing. His technique was to search for definitions of the key terms or concepts under discussion in some area of philosophical enquiry. He required of definition that the definiens (the statement of definition) should be synonymous with the definiendum (the expression or concept being defined) but contain no terms in common with it. The trouble with this is that even if such definitions were possible – and there is doubt that they are, even in the case of lexical definitions such as are commonplace in dictionaries – they constitute only one kind of definition, and the other kinds, for example analytic definitions (defining something by describing its structure or function) and definitions in use (allowing something to explain itself by showing it at work), are often not only more practical but more revealing; and therefore philosophically more valuable. Moore of course recognized the existence and utility of other kinds of definitions, but regarded his preferred kind as the ideal; and he also held that in the case of certain fundamental philosophical notions, such as that of ‘goodness’ in ethics, no definition is possible: such things are indefinable and primitive, and theory must begin with them rather than attempt to explain them.

Again without doubt, Moore’s style and personality were important in the early years of analytic philosophy. In the introduction to

OKEW

Russell wrote that analysis introduced into philosophy what Galileo had introduced into physics: ‘the substitution of piecemeal, detailed and verifiable results for large untested generalities recommended only by a certain appeal to the imagination’. This could equally well serve as a characterization of Moore’s painstaking style of philosophy, in which he takes a claim or idea and worries away at it endlessly until it is in its component pieces, neatly laid out. It is not a dashing style, but it is effective in its limited way. Moore had quite a number of imitators, but his aims and methods were chiefly critical; he did not make any philosophical discoveries. His main legacy is that he gave currency to the notion of a ‘naturalistic fallacy’ in ethics, which is to define the moral property of goodness in terms of some natural property like pleasure. The measure of a philosopher’s influence is the use made of his methods and ideas after he introduced them; by this measure Moore’s place at the beginning of twentieth-century philosophy does not compare with Russell’s. He did, however, help to set the analytical mood, and his famous mannerism – the shocked intake of breath with which he greeted philosophical remarks that seemed to him bizarre – helped to make generations of pupils and colleagues think much more carefully before they spoke or wrote.

In the foregoing discussion the implication might seem to be that analytic philosophy is a recent phenomenon. In the sense that many of its contemporary inspirations and techniques are drawn from the fundamentals of the new logic, this is true; but in another and equally important sense it represents a direct development of the tradition of Hume, Berkeley, Locke, and Aristotle. The first two of these thinkers – and especially the second – together with Leibniz provided Russell with much of his philosophical outlook. It is not difficult to see the similarity between Russell and Aristotle, for the latter based his metaphysics on his logic, and developed his logic for the purpose, just as Russell did.

No assessment of Russell as a philosopher can ignore the fact that, too often, his work is much less rigorous and careful than it would have been had he observed his own methodological counsels. There are indeed some notorious stretches of carelessness and superficiality in his work, and it is a standing wonder in the philosophical profession that his most successful and widely read book,

A History of Western Philosophy

, arguably the source of most people’s knowledge of philosophy, is – despite its many other virtues – in a number of places woefully inadequate as philosophical discussion. He made mistakes which students are now on their guard against in their earliest essays; for example, the ‘use-mention’ distinction, which marks the large difference between actually using an expression and talking about it. In the preceding sentence I used the word ‘expression’; I am now mentioning it, marking the fact by enclosing it in quotation marks. There are many occasions in philosophical debate where the distinction is crucial, a point that can be simply made by noting that very different things are meant by ‘Cicero has six letters’ and ‘ “Cicero” has six letters’.

Russell’s occasional insouciance about the need to be finicky (an inescapable duty in philosophy, if one is to be exact, clear, and rigorous: philosophy also requires imagination and creativity, but unless imagination is combined with precision it gets no one far) has irritated some. Reviewing

Human Knowledge

, Norman Malcolm described it as ‘the patter of a conjurer’. Paradoxically, Russell raised standards a long way in philosophical debate, but by the exigent levels those standards have reached, he is himself now sometimes found wanting.

These complaints are, however, minor. In most cases where Russell sails rapidly past qualifications and minutiae in his marvellous prose, beguiling us with his wit, such problems as he causes are not very great if the reader is alert. In any case Russell was aware of the fact that he sometimes went too fast. He was impatient with the kind of pedantry that is happy only when up to its neck in footnotes. He was anxious for practical results, for a working, stable view of the best grounding in experience that science can have. In some of his later work especially, his attitude was that if the larger outlines of a theory were plotted, its details could be filled in later. Even then his ideas are stimulating and sometimes novel.

But these remarks, one notes, apply only to Russell in a hurry, working in charcoal rather than oils. At his best his philosophical work is rich, detailed, ingenious, and profound. This is particularly true of what he wrote in the period between 1900 and 1914. The papers collected in

Logic and Knowledge

speak for themselves in this respect. What R. L. Goodstein says of some of the work in

Principia –

‘In certain respects the

Principia

represents a peak of intellectual attainment; in particular the ramified theory of types with the axiom of reducibility is as subtle and ingenious a concept as is to be found anywhere in the whole literature of logic and mathematics’ (‘Post

Principia

’, in Roberts,

Russell Memorial Volume

, 128) – can be applied to some of Russell’s more important philosophical writings. This is high praise indeed.

The graph of reputation has an almost invariable curve. It rises during life, and even if it dips in the fading years it makes a jump at the time of obituaries and memorials. Then it plunges and lies flat for a generation. But at length it rises again and finds its proper level in the estimation of posterity. Russell died in 1970; in the decades since then his name – but not, as much in the foregoing pages shows, his real influence – has been present only in particular connection with those topics in philosophy where his work is central: chiefly in discussion of reference and descriptions, in analyses of existence, and in the recent history of the theory of perception. One reason for this sidelining into footnotes is that for a time the later philosophy of Wittgenstein (who bucks the trend of the graph; immediately after his death there were three decades of enthusiastic discipleship, but his gifts as a philosopher – great though they are – are now more soberly appreciated) opposed something quite different to the Russellian style of analysis. In fact, most people working in philosophy continued in Russell’s style, but the celebrity of Wittgensteinian ideas and the energy of his disciples almost gave the contrary impression. The key here is Ryle’s remark that Russell did not seek or desire to found a school of disciples: ‘Russell taught us not to think his thoughts but how to move in our own philosophical thinking. In one way no one is now or will ever again be a Russellian; but in another way every one of us is now something of a Russellian.’

Generally speaking, thinkers accumulate disciples when they offer attractive-sounding answers to the great questions of philosophy (which, in more popular garb, are the great questions of life). Russell was sceptical about answers, although he vigorously sought them. In

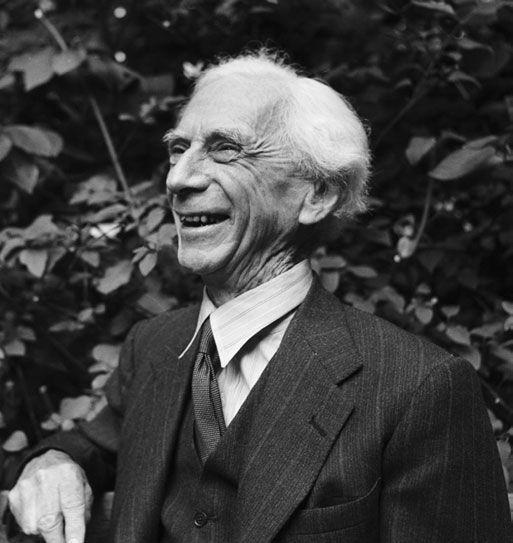

13.

Portrait of Russell.

the conclusion of

The Problems of Philosophy

, speaking of the value of philosophy, he wrote:

Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions, since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves, because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination, and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes the highest good.

By whichever measure one chooses, Russell, who contemplated many universes, is a great mind. He changed the course of philosophy and gave it a new character. There are very few figures in history of whom, with respect to their own sphere of activity, this can be said. And even then, some of these achieved it by accident or one momentary endeavour, as did – for good and ill respectively – Alexander Fleming and Gavrilo Princip. Russell, in contrast, achieved it by monumental means: in many books, articles, and lectures, over many years, across many continents. In the company of such as Aristotle, Newton, Darwin, and Einstein he is, therefore, a truly epic figure.

Further reading

Russell’s works remain their own best introduction, but there is a large literature on Russell and the various aspects of his philosophy, some of which carries much further the debates he started. A. J. Ayer’s

Bertrand Russell

(Fontana, 1972) and

Russell and Moore; The Analytical Heritage

(Harvard University Press, 1971) provide a sympathetic introduction. R. M. Sainsbury’s

Russell

(Routledge, 1979) gives an absorbing technical discussion of Russell’s central work. Peter Hylton’s

Russell, Idealism and the Emergence of Analytic Philosophy

(Clarendon Press, 1990) is essential reading for any serious study of Russell’s thought. Nicholas Griffin’s

Russell’s Idealist Apprenticeship

(Clarendon Press, 1991) is an excellent detailed study of Russell’s early work in philosophy.