Save the Cat! (25 page)

Authors: Blake Snyder

Deal!

Maybe the king of the logline working today, the man with a thousand pitches at his command, is producer Bob Kosberg. Bob makes a sale or two every month. He's amazing. Working with writers on ideas of his own, and theirs too, he can conceptualize

better than anyone in the business and can weed out the clunkers from the winners with lightning speed. Every time he walks into the room, he has a new one to pitch.

Deal!

I, too, have done specialty pitches. The one I remember most was a hilarious failure. My first partner, Howard Burkons, and I had a movie idea called

Big Girl On Campus,

which was basically

Tootsie

goes to college. Howard volunteered to do the pitch dressed as a woman, in full makeup and outfit, just to get the idea across that it was possible. And as great as Howard looks in a dress, we did not sell

B.G.O.C.

No deal!

Howard did, however, get asked out at Disney.

I have had success with specialty marketing. During the spec sale frenzy of the early '90s, the buzz surrounding any virgin screenplay that was on the block for sale was huge. Word that a new script was going "out to the town" started days and weeks beforehand. The script was

tracked

by development execs, and their bosses often yelled and screamed demanding to be put on the list.

In this atmosphere, making your script sale special became a fad. For the sale of a script called

Ticking Man,

ticking clocks with alarms all set to the same time were sent out to executives prior to getting the script. The alarms went off all over town at the moment messengers arrived with the script. Talk about building and paying off tension!

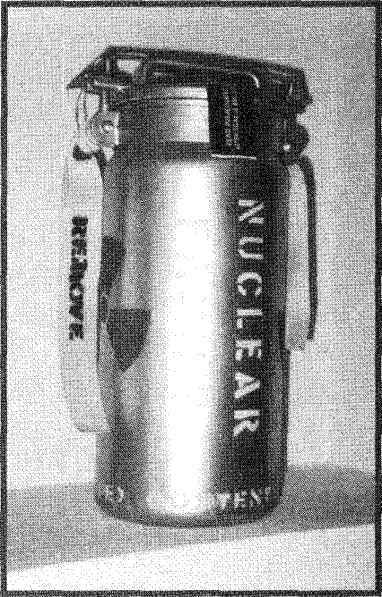

The

Nuclear Family

Script Containment Unit (1992)

When Jim Haggin and I were ready to send out our spec script,

Nuclear Family,

we decided to package it in artistically designed

"radioactive script containment units," into which we stuck the script as our way of setting the mood. We made 20 of these from materials we bought at an Army surplus store; only the most special producers were on the list to get one. After clearing this special delivery with the security gate at every studio (these things looked so much like a bomb we didn't want any false red alerts), the send-out was coordinated by our agent, Hilary, as messengers delivered our script containment units in a flurry of activity all over town. By the time the day was over, Jeffery Katzenberg at Disney and Steven Spielberg at Amblin had personally gotten on the phone to make a bid.

A year or so later, Colby Carr and I stuffed several dozen kid's backpacks with a million dollars in play money for Hilary to send out

Blank Check

— basically the storyline of the script in a finely made, 3-D souvenir.

Each of these specialty presentations resulted in a million-dollar sale. And headlines in

Variety

the next day noted the marketing innovations and the bidding war both inspired. For our part, we always devised these because we were genuinely enthusiastic about our script, and wanted to get the reader in the mood —just like a good marketing campaign gets a nationwide audience in the mood to see a summer blockbuster. It's a truism that the easiest people to sell are salesmen. I am a sucker for a great campaign of any kind. And so are the executives in Hollywood. They like a good show as much as the next person and are more likely to applaud the effort. Besides, we had a ball doing it!

Of course this kind of marketing is oldhat now. No one does these little tricks anymore. It's doubtful this type of selling will come back. Too many scripts that were bought did not get made and the spec script craze has died. Studios nowadays don't like to be that out of control when it comes to bidding on scripts, so they don't get into bidding wars as often or as eagerly as they used to. But it was fun while it lasted! Who knows what the next innovative tactic will be — via the Internet maybe? — to get the attention that will set your script apart in the crowd. After all, this is a business that still likes special effects, surprise, and showmanship.

IT IS WHAT IT IS

Okay. Last words on the entire subject. I am a little teary about ending this book. It's been fun to write and I hope that in some way it's been helpful to you. I have been honored to be a part of this business from the time I was a very little kid. I've had great adventures, lots of truly creative moments, and met some of the most amazing people. It's been a great ride.

I've also been faced with terrible self-doubt and self-recrimination. You get bumped in this business, and want to throw in the towel from time to time. But if it's in your blood, like it's in mine, you learn to persevere. And you get as much education from failure as success. If you keep trying and stay focused, you can have any prize in the firmament. All you have to do is keep working at it, have a great attitude, and know that today just might be "the day. "

Right before Colby Carr and I ever sent a script out, gave it to our agent, or to the producer, we had a little saying to take the sting away. We knew that we had done our best. With Colby, as with all my writing partners, we work hard for the money. And we are harder on ourselves than any critic could possibly be. Just before we dropped that script in the mail or surrendered it to the messenger, Colby and I would say: "It is what it is." That phrase means that certain artistic projects, when combined with the need for those projects to make a profit, are penned in by demands that you must meet. If you meet them satisfactorily, if you've done your job, if you've covered yourself from every angle, if you've met every criteria and done so creatively, that's all you can do. You've done your best.

The rest is fate.

It is what it is.

The business is what it is too. And while I often rebel against it, or try to bullhead my way past it, there's no way around it. "They," meaning the people who run the studios and make the decisions, do all kinds of things that drive creative people like us mad, but they are in charge. Yes, they buy into someone's "heat' and ignore others, more talented, who are unknown. They often don't read scripts thoroughly. And they are more interested in the headline and the opportunity you represent than your growth as an artist.

But that's the nature of business.

It is what it is.

You must find a life within the confines of "It is what it is." This is where your skills as a bullhead will save both you and your sanity. And while I've made fun of this trait throughout this book, I do it as a means of challenging you to be more so: Whatever you do, don't stop being a bullhead. The powers-that-be can take away a lot of things. They can buy your script and fire you, or rewrite it into oblivion, but they can't take away your ability to get up off the mat and come back swinging — better and smarter than you were before.

Most of all, you must try to find the fun in everything you write. Because having fun lets you know you're on the right track. So that when you write those two dazzling words, FADE IN:, the hundredth time, you're as excited as you were when you wrote them the first.

GLOSSARY

_

FREQUENT TERMS IN USE IN THE 310 AREA CODE

ARC

— This denotes the changes a character experiences as tracked from the beginning, through the middle, to the end of a screenplay. Most often heard in development meetings as in: "What's the arc of the hero?" and "Are these characters arcing enough?" To which you think to yourself: "What is the arc of my patience to sit here and listen to this?"

AT THE END

OF

THE DAY

- A phrase used by agents and managers to indicate they are about to give you bad news, i.e., "We love your script and think it would be

great

for Julia, but at the end of the day does she really need to do a musical set in the Middle Ages?" Also when you are most likely to be called by said agent or manager with this bad news.

BLACK HOLES

— These are the spots in your beat sheet, step outline, or places on The Board that you have no idea how to fill with story. Looking at black holes will cause you to wonder how you got into the business. You could have gone to law school or joined the Army but no, you had to do this!

BLOCK COMEDY

- A low budget, domestically oriented, family film. It is so low tech and requires so few company moves, you can shoot it on the backlot — as they did with

The 'Burbs.

I first heard this term at Disney when we were discussing a script we had sold to them called

Poker Night.

And it all takes place — on the block. "We want more of these," said the executive in charge. "You know, a block comedy!" I had never heard the term before. It may just be his term, but I like it, and now it's mine.

BOARD, THE

— A corkboard, blackboard, or artist's notebook that divides a screenplay-in-progress into four equal parts: Act One, the first half of Act Two, the second half of Act Two, and Act Three. It is the workout space where, using index cards, pushpins, colored Pentels, etc., you can try your best ideas and see what they look like, and then begin to winnow them down. If done right, you'll end up with 40 scenes that make a movie, all laid out neatly on The Board in your office or workroom... along with blood, sweat, and tears.

BREAKING THE FOURTH WALL

- A filmmaker's inside joke that makes the audience realize they are watching a film. The fourth wall is an invisible one that allows the audience to look into the lives of characters on stage. And breaking it lets the characters, essentially, look back. This "takes you out of the story." Sometimes it works, as when Woody Allen speaks to the audience in

Annie Hall.

But most times it does not, as when Robin Williams "breaks character" (like in

Aladdin).

BOOSTER ROCKET

— There are spots in any screenplay that are potentially dull stretches. Usually these are found right after "big moments" like after the Act One break and sections where the action is petering out, like at the end of Act Two. This is a time to stick in a booster rocket to get us past these spots. John Candy in

Home Alone

is the classic example. The tale of a Mom (Catherine O'Hara) getting home to her child is starting to drag around the end of Act Two. So when John Candy and his polka-band cohorts show up, it's just what the script doctor ordered. Another booster rocket character is the manicurist in

Legally Blonde.

She arrives just when we're growing weary of Elle Woods' law school saga, just after the break into Act Two of that screenplay. Both these characters rocket us past these potential slow spots.

CALLBACKS

— Bits, images, character traits, and metaphors that are set up in Act One and then recalled later in the movie. Often the callback explains what that obvious set-up was about. In

Back to the Future,

the flier upon which Marty McFly's girlfriend writes "I Love You" reminds Marty of the clock tower and the electric storm in 1955

that he

needs to power his DeLorean back to

1985.

This is a nice callback. Other callbacks are less plot-oriented and remind us of a character's growth, harkening the past to show change or to re-emphasize a joke by reminding us of its origins.