Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (63 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Each of the houses that anchor Jackson’s final three completed novels—

The Sundial

,

Hill House

, and

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

—has its own distinct personality and indeed functions as a kind of character in the book. Her interest in houses and their atmosphere extends back to the beginning of her career: to her early fiction, which so often describes the efforts of women to create and furnish a home, and to the first family chronicles she wrote for women’s magazines. Her preoccupation with the roles that women play at home and the forces that conspire to keep them there was entirely of a piece with her cultural moment, the decade of the 1950s, when the simmering brew of women’s dissatisfaction finally came close to boiling over, triggering the second wave of the feminist movement. In

Hill House

, which appeared in 1959, Jackson gathered powerfully all the objects of her longtime obsession: an unhappy, unmarried woman with a secret trauma; the simultaneous longing for a mother’s love and fear of its control; the uncertain legacies handed down by previous generations; and finally the supernatural as a representation of the deepest psychic fears and desires. The result, a masterpiece of literary horror on a par with Henry James’s

The Turn of the Screw

, is arguably her best novel, and certainly her most influential.

As with all great ghost stories, readers have been divided over how to understand

Hill House

. Are the ghosts intended to be real, or are they the psychological manifestations of Eleanor, the book’s most disturbed character? On this fundamental question the novel remains deliberately enigmatic. But what cannot be questioned about

Hill House

is Jackson’s technical mastery. From the book’s first lines, her absolute control over the rhythm and timbre of her sentences is obvious:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

No mere ghost story has ever been so beautifully written. Stephen King, one of Jackson’s most devoted fans, has written that “there are few if any descriptive passages in the English language that are finer” than the opening to

Hill House

. “It is the sort of quiet epiphany every writer hopes for: words that somehow transcend the sum of the parts.”

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality

. The line reads at first like the start of a different book: what does it have to do with the description of the house that follows? But what it reveals is of crucial importance for the story to come. Hill House is itself a living force that adapts to its inhabitants and responds to their personalities and their histories. The fact that it is “not sane” shows that the circumstances that exist there, supernatural though they may appear, in fact constitute “absolute reality,” or at least one form of it. “An atmosphere like this can find out the flaws and faults and weaknesses in all of us, and break us apart in a matter of days,” Dr. Montague says. What Eleanor Vance will face inside is not a haunting from another world, but a confrontation with the reality of her psyche—the world of her own secrets and fears.

THE NOVEL BEGINS

with Eleanor’s journey to Hill House. Thirty-two years old, she has spent all her adult life dutifully caring for her mother, “lifting a cross old lady from her chair to her bed, setting out endless little trays of soup and oatmeal, steeling herself to the filthy laundry.” Since her mother’s recent death, she has been living with her sister, whom she hates. Eleanor cannot remember a time when she was happy: “Her years

with her mother had been built up devotedly around small guilts and small reproaches, constant weariness, and unending despair.” Having spent so much time in isolation, she suffers from painful self-consciousness, which makes her anxious at even the thought of a simple conversation. When a letter comes inviting her to join the group of researchers at Hill House, she does not hesitate: all her life, she has been clinging to the belief that “someday something would happen.”

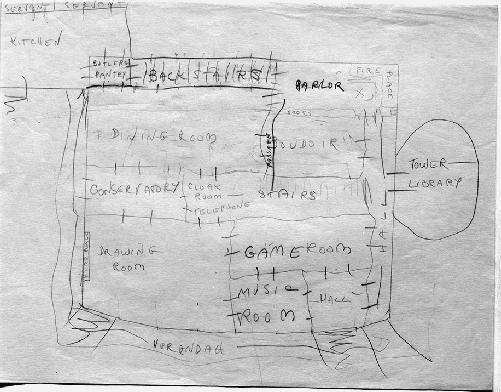

Jackson’s sketch of Hill House (downstairs).

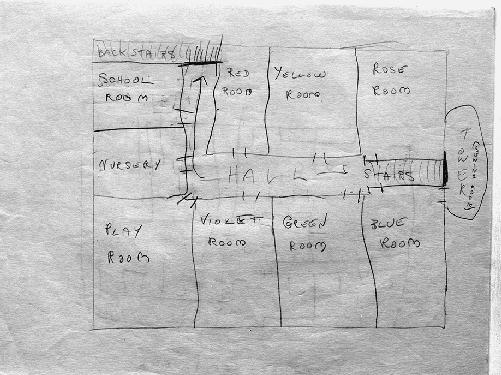

Jackson’s sketch of Hill House (upstairs).

Like Dr. Wright in

The Bird’s Nest

, Dr. Montague is a character

Jackson might have borrowed from a Trollope or Thackeray novel. He is “round and rosy and bearded and looked as though he might be more suitably established before a fire in a pleasant little sitting room, with a cat on his knee and a rosy little wife to bring him jellied scones,” and his cure for insomnia is an hour of Samuel Richardson before bed. He has sent invitations to a dozen people he selected based on evidence of their prior psychic ability; in the end, only two turn up. For Eleanor, the relevant incident was the shower of stones that fell on her childhood home for three days after the death of her father, “during which time Eleanor and her sister were less unnerved by the stones than by the neighbors and sightseers who gathered daily outside the front door, and by their mother’s blind, hysterical insistence that all of this was due to malicious, backbiting people on the block who had had it in for her.” Theodora, who arrives next, is clairvoyant, with disconcerting powers of empathy. She is Eleanor’s opposite, an artist, bright and cheerful and flirty, with a bohemian lifestyle and a partner whose sex is pointedly never specified. (In early drafts of the novel, she is openly lesbian.) After spending only a few hours with her, Eleanor already realizes that it is “oppressive to be for long around one so immediately in tune, so perceptive,” as to be able to read minds. Finally they are joined by Dr. Montague and Luke Sanderson, the heir to the estate, whose aunt—the owner of Hill House—has insisted that a member of the family be present during the investigation.

It took several tries—as was typical—for Jackson to settle on the exact source of Hill House’s horror. In an early draft, the main character, arriving at the house, knocks on a heavy wooden door. In the next, she finds a knocker with a lion’s head. In the final version, the knocker Eleanor uses has become a child’s face. She is entering a family home, but it is a home that has gone badly wrong. The house was built by a man named Hugh Crain, who, like the first Mr. Halloran in

The Sundial

, had a vast and unexplained fortune. The disasters began at once. Crain’s first wife died when her carriage overturned in the driveway, leaving him to raise their two little girls. The second Mrs. Crain died in a mysterious fall. Later he was married again, this time to a woman who was consumptive, and left the girls behind at Hill House, traveling with his new wife from one European spa to another. After she died, Crain closed Hill House

and sent his daughters away; they would later quarrel bitterly over which of them would inherit the house. The elder sister wound up living there with a female companion, a girl from the village, who claimed after the sister’s death that she was the legal inheritor of the house. The younger sister lost a fight against her in court, but hounded her until she committed suicide. “Gossip says she hanged herself from the turret on the tower, but when you have a house like Hill House with a tower and a turret, gossip would hardly allow you to hang yourself anywhere else,” Dr. Montague remarks. As if to symbolize the children’s unhappiness, a distinctive cold spot, a classic sign of haunting, lies just before the doorstep of the nursery: “the heart of the house,” one character calls it.

The supernatural manifestations begin on the second night. Eleanor awakens to a sound she believes is her mother knocking on the wall to summon her; it turns out to be an unknown presence banging on the bedroom doors, seemingly in search of someone inside. Soon it becomes clear that whatever is in the house has its eye on Eleanor. Mysterious messages appear on the walls written in chalk and in blood: “Help Eleanor Come Home.” At one point Dr. Montague’s wife, a blowzy medium who arrives in the midst of the weeklong investigation to provide some much needed comic relief, insists that the group contact the house’s spirits using a planchette, a device similar to a Ouija board. The message that arrives is addressed to Eleanor. “What do you want?” Mrs. Montague asks. “Home,” comes the response. Over the next night of manifestations, the pressure inside Eleanor’s head mounts unbearably. “It is too much, she thought, I will relinquish my possession of this self of mine, abdicate, give over willingly what I never wanted at all; whatever it wants of me it can have. ‘I’ll come,’ she said aloud.”

At one point the characters try to define fear, and their answers are notably similar. “I think we are only afraid of ourselves,” Dr. Montague suggests. “Of seeing ourselves clearly and without disguise,” Luke elaborates. Theodora simply phrases it a different way: “Of knowing what we really want.” Eleanor confesses her own personal fear: “I am always afraid of being alone.” In the crucial scene that immediately follows, Eleanor awakens in the night to hear a voice babbling in the next room and clutches at the hand of Theodora, sleeping beside her. The voice turns into

the cry of a child, sobbing, “Please don’t hurt me. Please let me go home.” She screams; the lights go on, and she sees that Theodora is not next to her after all, but in bed across the room. “God God,” Eleanor says, “whose hand was I holding?”

If this, as Jackson wrote in her notes on one of the drafts, is the “key line” of the novel, what does it mean? The critic Daryl Hattenhauer has argued that Eleanor is holding her own hand, but the novel indicates that this is not the answer: at one point during the scene Eleanor clutches the other hand with both of hers. Another scholar writes, similarly, that Eleanor’s fear comes from her disillusionment: she thought that she had company in the dark, but finds herself alone yet again. An alternate interpretation also seems possible. The people we hold by the hand are our intimates—parents, children, spouses. To discover oneself clinging to an unidentifiable hand and to ask “Whose hand was I holding?” is to recognize that we can never truly know those with whom we believe ourselves most familiar. One can sleep beside another person for twenty years, as Shirley had with Stanley by this point, and still feel that person to be at times a stranger—and not the “beautiful stranger” of her early story. The hand on the other side of the bed may well seem to belong to a demon.

But it is, once again, a poisonous mother-daughter relationship that is central to

Hill House—

just as Shirley’s poisonous relationship with her own mother, whose relentless criticism had conditioned her to accept Stanley’s belittling and betrayal, underpinned the damaging dynamic of her marriage. “Fear and guilt are sisters,” says Dr. Montague, and Eleanor’s anxiety is rooted in her guilt over her mother’s death, which, she finally confesses, happened because she failed one night to respond to her mother’s knocking on the wall. (When Shirley failed to respond on time to Geraldine’s missives, regardless of their content, her mother took it poorly.) Eleanor reversed roles with her invalid mother, she the caretaker and her mother the dependent; in Hill House the roles reverse again, the hallways filled with ghostly children who pound on the doors and laugh at the keyhole but will never be allowed inside. In the end, the house itself takes on a kind of maternal role—“housemother,” Luke puns—its furniture “padded” and “motherly,” yet “hard and unwelcoming”; like the burned-out tenement Shirley glimpsed from the train, it is “vile,”

“diseased,” “unclean,” just as Eleanor’s mother was in her illness. Eleanor’s final crescendo of insanity transforms her into a child of the house, dancing and playing in its rooms. In her “Experience and Fiction” lecture, in which she discusses the writing of

Hill House

, Jackson writes that she sleepwalked one night and found on her desk the next morning a piece of her yellow writing paper on which she had scrawled, “DEAD DEAD.” No such paper can be found among the drafts of the novel in her archive; instead, there is a page on which she scribbled, “FAMILY FAMILY.” In the world of the novel, the two are essentially the same.