Steve Jobs (40 page)

Authors: Presentation Secrets

double-tapping the screen to bring the map closer. Fourth, he

selected the option to replace the map with satellite photographs.

He brought up a live image of the Washington Monument. “Isn’t

that incredible, right on my phone?” he said. Finally, he visited

the Eiffel Tower and Roman Colosseum and showed both in the

satellite view. He concluded by saying, “Satellite imagery right

206

REFINE AND REHEARSE

on our phone. Unbelievable. Isn’t that incredible?

”4

Jobs did rely on his script for the demo, but it had been written and rehearsed

extensively so that only a few key words were all he needed to

prompt him.

Yes, Steve Jobs appears conversational, but by now you should

know that being “conversational” requires a lot of practice. And

how

you practice makes all the difference. Use the slides as your teleprompter, sticking to one theme per slide and several supporting points. If you forget some of your supporting points, you

will at least have hit the main theme. Above all, toss the script.

Notes will interfere with the emotional connection you need to

establish with your audience, detracting from the presentation

experience. Theatrics can turn an average presentation into an

extraordinary event. A script gets in the way.

D IR EC TO R ’ S N OT E S

Don’t read from notes except in special circumstances in

which you must follow a step-by-step process, such as a

demonstration.

When you must read from notes, create no more than

three or four large-font bullet points on one note card or

sheet of paper. Create one note card per slide. If you’re

using speaker’s notes in Keynote or PowerPoint presenta-

tion software, keep your bullet points to no more than

three or four. One is even better.

Use the visuals on your slide to prompt you to deliver just

one key theme—one main message—per slide. Think

“one theme per slide.”

SCE

SCENNEE 1

188

Have Fun

Everyone wants a MacBook Pro

because they are so bitchin’.

STEVE JOBS

In 2002, the Mac OS X was brand new, and Apple was striving

to get customers and developers to embrace it. Jobs decided

to put the issue to rest, literally, at the Worldwide Developers

Conference.

As the presentation began, Jobs was not onstage. Instead,

white smoke surrounded a casket. Gloomy pipe-organ music

played in the background. Jobs finally emerged from behind a

curtain, walked to the casket, lifted the lid, and pulled out a

large-scale copy of OS 9, Apple’s previous operating system. The

audience got the joke immediately and started laughing and

applauding.

Jobs was committed to the joke and took it further. With a

copy of OS 9 lying in the casket, Jobs pulled out a sheet of paper

and eulogized the software. “Mac OS 9 was a friend to us all,” he

started.

He worked tirelessly on our behalf, always posting our appli-

cations, never refusing a command, always at our beck and

call, except occasionally when he forgot who he was and

needed to be restarted. He came into this world in October of

1998 . . . We are here today to mourn the passing of OS 9. He

is in the great bit bucket in the sky, no doubt looking down

upon this with that same smile he displayed every time he

booted. Mac OS 9 is survived by his next generation, Mac

207

208

REFINE AND REHEARSE

OS X . . . Please join me in a moment of silence as we remem-

ber our old friend, Mac OS 9.

”1

Jobs walked back to the casket, put the box back in, closed the

lid, and gently laid a rose on the top. The audience ate it up. Jobs

made his point, and he had a lot of fun doing it.

Jobs has fun, and it shows. Despite relentless planning and

preparation, hours and hours of rehearsal, and near-fanatical

devotion to getting every slide and every demo just right, some-

times things go wrong, but Jobs doesn’t let the small stuff get to

him. He’s going to have fun, whether a demo works or not.

“Let’s take a look at how big this market is,” said Jobs as he

described the market opportunity for the iPhone at Macworld

2007. Suddenly, his slides failed to advance. “My clicker’s not

working,” he said. As he walked to the right of the stage to check

the computer, the slide seemed to advance. “Oh, maybe it is

working. No, it’s not.” Jobs picked up another clicker but it, too,

failed to work. He smiled and said, “The clicker is not working.

They’re scrambling backstage right now.

”2 Th

e audience laughed, and after a few more seconds of trying to fix the clicker, Jobs

simply paused, smiled, and told the following story:

You know, this reminds me, when I was in high school, Steve

Wozniak and I—mostly Steve—made this little device called

a TV jammer. It was this little oscillator that put out frequen-

cies that would screw up the TV. Woz would have it in his

pocket. We would go out to a dorm at Berkeley, where he

was going to school, and a bunch of folks would be watching

“Star Trek.” He would screw up the TV, someone would go

to fix it, and just as they had their foot off the ground, he’d

turn it back on, and then he’d screw up the TV again. Within

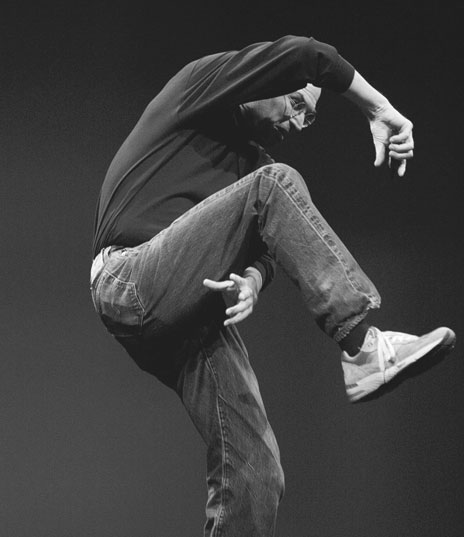

five minutes, he’d have someone like this [contorts his body;

see Figure 18.1] . . . OK, it looks like it’s working now

.3

In this one-minute story, Jobs revealed a side of his personality

that few people get to see. It made him more human, engaging,

and natural. He also never got flustered. I have seen even some

experienced presenters get derailed over smaller problems.

HAVE

FUN

209

A YouTube user posted a five-minute clip showing dozens of

Jobs “bloopers.

”4

The number of things that have gone wrong is surprising given the level of extraordinarily detailed practice

that goes into a Steve Jobs keynote. This blooper reel proves that

even the best-laid plans go awry from time to time: a slide may

not advance, a wrong slide may come up, and a demo may not

work. These things happen to even the best-prepared presenter,

and they can, and probably will, happen to you at some point.

The difference between mediocre presenters and a true mas-

ter such as Jobs is that when demonstrations do not turn out as

planned, Jobs reacts with a cool confidence. The audience sees a

showman in complete control of his material. If something fails

to work, Jobs does not dwell on it or call undue attention to the

Figure 18.1 Jobs demonstrates a prank he and Apple cofounder

Steve Wozniak would pull on unsuspecting college students.

David Paul Morris/Getty Images

210

REFINE AND REHEARSE

issue. He smiles, has fun, explains to the audience what they should have seen, and moves on.

Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff

During a demonstration of Apple TV at Macworld 2008, Jobs

brought up a live connection to Flickr, a photo-sharing site. Jobs

selected several categories to show the audience how photographs

could be served from the site and displayed on a wide-screen

television in a living room. Unfortunately, the screen went black.

After about twenty seconds of trying to retrieve the images, Jobs

simply turned to the audience, grinned, and said, “Well, I’m

afraid Flickr isn’t serving up photos on that one.

”5

Jobs doesn’t let anything ruffle him onstage. Instead, he

acknowledges the problem, continues the presentation, summa-

rizes the material, and enjoys himself. He concluded the Apple

TV demonstration by saying, “All of this from your wide-screen:

movies, TV shows, music, podcasts, photos from dot-Mac and—

when they’re serving up photos—Flickr! So, that’s what I wanted

to show you today. Isn’t that incredible?

”6

Jobs never loses his enthusiasm. The demo might not have gone perfectly, but that

doesn’t diminish the joy he has for the product.

No matter how much you prepare, something might, and

probably will, go differently from how you had planned. Notice

that I did not say something will go “wrong.” It goes wrong

only when you call attention to the issue or you let it ruin the

rest of your presentation. People are there to hear you, to learn

something new about a product, service, or initiative that could

improve their lives.

When a demo fails to come off as smoothly as Jobs had

rehearsed, he never loses his cool. He says something like, “Oops,

that’s not what I wanted” or “I need some help here, guys; this

thing isn’t working.” He will take a few moments to get it work-

ing, and he will do so very calmly.

In one presentation, Jobs could not get a digital camera to

work, so he had some fun with it, tossed it to an Apple employee

in the front row, and said, “I need an expert to fix it. It’s too

HAVE

FUN

211

technical for me. It’s pretty awesome when it works.

”7

That’s it.

It’s pretty awesome when it works.

Think about watching an ice-skater perform an intricately

choreographed routine. You know that the slightest mistake

could land the skater on her butt. When it happens, you wince,

but you hope the skater gets up to finish her routine on a high

note. The same applies to your audience. Nobody expects per-

fection except you. Your audience will forgive a blooper as long

as you get back on your feet.

During Jobs’s leave of absence for a liver transplant, much

had been written about what he revealed, how much he should

have revealed, and whether he should have revealed it sooner.

Jobs was clearly frustrated with the press, calling some report-

ers to chastise them about covering matters he wanted to keep

private. While bloggers and reporters were scrambling to get the

scoop on the exact nature of his illness, I was struck at how Jobs

kept his trademark good humor.

In September 2008, Jobs walked onstage at the WWDC and

said, “Good morning. Thank you for coming this morning. We

have some really exciting stuff to share with you. Before we do,

I just wanted to mention this.” He pointed to the slide behind

him, which had only one sentence: “The reports of my death

are greatly exaggerated.” “Enough said,” Job told the audience,