Streets of Gold (18 page)

“But my family will be

here

,” Pino had said to him long ago, and he remembered those words now, and realized that

his

family, the family of Francesco Di Lorenzo,

was

here. There was no family in Fiormonte; his mother and father were dead, Maria was dead, Emilia had left for Torino with her husband, who hoped to find work in the steel mills. The family was here. He had a beautiful, gentle wife whom he loved and cherished, and for whom he would work hard all the days of his life; he had a seventeen-year-old daughter who was engaged to be married; and a twenty-year-old daughter who was sure to marry soon herself, once she found the right boy, she was fussy, Stella, he liked that about her, she was not easy to please, his Stella, his star; and Domenico, such a smart boy, studying so hard at a very difficult high school in the Bronx, a ninety average, that was very good, they said, a ninety; and Luca, so tall, so gentle, who played the violin and piano beautifully, just like his cousin Rodolfo in Fiormonte... But no, Rodolfo had been killed in the war, Rodolfo was dead. The family was here.

here

,” Pino had said to him long ago, and he remembered those words now, and realized that

his

family, the family of Francesco Di Lorenzo,

was

here. There was no family in Fiormonte; his mother and father were dead, Maria was dead, Emilia had left for Torino with her husband, who hoped to find work in the steel mills. The family was here. He had a beautiful, gentle wife whom he loved and cherished, and for whom he would work hard all the days of his life; he had a seventeen-year-old daughter who was engaged to be married; and a twenty-year-old daughter who was sure to marry soon herself, once she found the right boy, she was fussy, Stella, he liked that about her, she was not easy to please, his Stella, his star; and Domenico, such a smart boy, studying so hard at a very difficult high school in the Bronx, a ninety average, that was very good, they said, a ninety; and Luca, so tall, so gentle, who played the violin and piano beautifully, just like his cousin Rodolfo in Fiormonte... But no, Rodolfo had been killed in the war, Rodolfo was dead. The family was here.

Fiormonte had been the family, but now the family was here.

He sat up and looked at Pino, and Pino abruptly stopped singing.

“È qui,”

he said to his friend. “

La famiglia è qui.”

he said to his friend. “

La famiglia è qui.”

“Cosa?”

Pino asked.

Pino asked.

Francesco watched his daughter as she went to the bandstand and began talking to the drummer, who kept playing all the while she chatted and smiled at him. On the dance floor, his other daughter, his angel Cristina, danced in the arms of a man who not ten minutes before had called him “Papa.” Francesco was forty-two years old. For the longest time he had been twenty-four, and had dreamed of going home. He was now forty-two, and knew he would never go home again, never return to Italy, never.

The family was here. He was the head of the family, and the family was here.

Home

was here.

Home

was here.

He suddenly covered Pino’s hand with his own and squeezed it very hard.

IIThey stood on line outside the free employment agency, four thousand men every day of the week, six thousand on Mondays, when presumably the chances of finding work were higher. There was not much talking on the line. Most of the men knew they would not get a job, but they were still trying, their hopelessness was not yet total. They waited in the bitter cold for two hours, sometimes three, and then a thousand of them were led inside, following each other up the long flight of steps to the huge open room with desks and telephones and men with megaphones. They filled out forms — name, address, age, education, religion, color. And then they waited for the phones to ring. A ringing phone meant a job offer. One of the megaphone men would answer a phone, and then call out a job — “Man needed to shovel snow, forty cents an hour” — and there would be a rush to the desk, and the job-seekers would be warned again to stay in line behind the rope, and another phone would ring, and a megaphone man would announce, “Skilled mechanic, seventy-five cents an hour, might be a full day’s work,” and another rush to the desk, and another warning. Each of the men knew if he didn’t get a job in the hour allotted to him upstairs, he would have to leave and come back the next day, and fill out the form again, and wait another sixty minutes for that phone to ring. If nothing came during that length of time, they would all be herded out of the big room again, and another thousand men who’d been waiting on line outside the building would be led upstairs to listen for those ringing telephones that meant someone had a job offer for them. Two hundred, three hundred men found temporary work each day. Most found nothing. They would wander over to the park afterward, and sit on benches and stare at their shoes. It was better than going home.

I was blind, and I did not see those long lines’ outside the employment bureaus and the soup kitchens. I did not know that men in shabby overcoats and caps stood on street corners selling apples for five cents apiece. I did not see the mob of depositors outside the bank on 116th Street, clamoring to withdraw lifelong savings, storming the big brass doors after they were closed. My grandmother Tess lost three thousand dollars when they shut down that bank. The Hooverville shacks that sprang up overnight along the shores of the Hudson were described to me by my mother, but I never saw them. Dust storms and floods, natural disasters that perversely aggravated the nation’s miseries, were something I heard about only on the radio or in the Movietone newsreels whenever my mother took me to the pictures, but I could neither see nor visualize events of such enormity. An angry mob of unemployed veterans marching on Washington and demanding World War I bonuses was a spectacle I could not have conjured in my wildest imaginings.

This was the winter of our despair, but I did not realize it. I was part of something far more exciting.

I was in on the creation of a myth.

In 1932, a month short of my sixth birthday, I began attending the Blind School, as it was called by fourteen of its pupils, including me. Actually, it was a standard New York City elementary school, except that it also had a class of fourteen blind kids. The school I should have gone to, had I been able to see, was P.S. 80 on 120th Street near First Avenue. But P.S. 80, like most of the other schools in the city, simply wasn’t equipped to teach the sightless, and so we were bused from surrounding neighborhoods to 104th Street and Third Avenue, where a classroom with a specially trained teacher and suitable equipment had been set up in the old brick building there (since torn down, I understand). We rarely had contact with the sighted kids in the school, except for joint activities like assembly programs and school plays. For the most part, the fourteen of us were isolated in a virtual one-room schoolhouse, with the ages of the pupils ranging from five to eleven. Miss Goodbody taught all our subjects, and referred to us aloud all the time as “My dear little darlings.” This was not condescending; she adored children, and all the kids at the school, sighted

or

blind, were her dear little darlings. But

we

referred to ourselves as “little blind bastards.” Some of us were less blind than others, of course, but none of us could see worth a damn, and the appellation seemed appropriate — even if it

did

try to disguise self-pity with arrogance.

or

blind, were her dear little darlings. But

we

referred to ourselves as “little blind bastards.” Some of us were less blind than others, of course, but none of us could see worth a damn, and the appellation seemed appropriate — even if it

did

try to disguise self-pity with arrogance.

We were cruel to each other sometimes.

We were blind, but we were children.

Despite the loving care of Miss Goodbody, we remained convinced that we were misfits, a freakish band of outsiders isolated in a classroom at the end of the hall, or being marched to assembly or play in a chattering sightless unit, the corridors around us going mysteriously still as we passed through. Unlike Orphan Annie’s countless legions, we wore the badges of

our

secret society without pride or passion. Little blind bastards, we were... and ashamed of it, I suppose. Ashamed because we felt if only we’d been

better

(Christ knows where; in the womb?), we wouldn’t have been born blind. We could not accept the possibility that our parents, those sources of sustenance, comfort, and support, had done anything to deserve the likes of us, and so we figured we ourselves were somehow to blame. And no matter how hard Miss Goodbody tried to engender a feeling of self-worth in us, we always came away with a single inescapable fact: we were blind. We were not as good as other people. We were inferior products. Why was anyone bothering with us at all? Why didn’t they simply throw us into the nearest incinerator?

our

secret society without pride or passion. Little blind bastards, we were... and ashamed of it, I suppose. Ashamed because we felt if only we’d been

better

(Christ knows where; in the womb?), we wouldn’t have been born blind. We could not accept the possibility that our parents, those sources of sustenance, comfort, and support, had done anything to deserve the likes of us, and so we figured we ourselves were somehow to blame. And no matter how hard Miss Goodbody tried to engender a feeling of self-worth in us, we always came away with a single inescapable fact: we were blind. We were not as good as other people. We were inferior products. Why was anyone bothering with us at all? Why didn’t they simply throw us into the nearest incinerator?

When I began taking piano lessons from Miss Goodbody, I told all the kids in class that I was

better

than they were.

They

were the little blind bastards;

I

was musical — Miss Goodbody had said so. Whenever I wore a new suit to school, even though I couldn’t see what the hell it looked like, I boasted about my grandfather the tailor, and told all the other kids he made clothes for very rich people, a lie no one ever believed. And even though I recognized this same cruelty in the other blind kids whenever it was directed at me, I turned insight into sight and told myself that only

I

was smart enough to see through the ploy (to

see

through it, mind you), and understand that a bragging little blind bastard was nonetheless blind, a part of the club, a freak, an outcast — a

nothing

.

better

than they were.

They

were the little blind bastards;

I

was musical — Miss Goodbody had said so. Whenever I wore a new suit to school, even though I couldn’t see what the hell it looked like, I boasted about my grandfather the tailor, and told all the other kids he made clothes for very rich people, a lie no one ever believed. And even though I recognized this same cruelty in the other blind kids whenever it was directed at me, I turned insight into sight and told myself that only

I

was smart enough to see through the ploy (to

see

through it, mind you), and understand that a bragging little blind bastard was nonetheless blind, a part of the club, a freak, an outcast — a

nothing

.

The thing I liked most about the Blind School was those piano lessons with Miss Goodbody, who had discovered during our Bluebird-Blackbird sessions in the school auditorium that I could accurately reproduce by voice any note she struck on the keyboard. This must have astonished her. I was officially a Blackbird with a terrible singing voice, but I never sang off key, and she was beginning to find out I had perfect pitch. Today, I can identify as many as five notes being struck simultaneously on the keyboard, even if they’re cacophonous. That’s not an extraordinary feat; you’re either born with a good ear or you’re not. But Miss Goodbody took it as a sign from above that I was destined to study the piano. Since the lessons were free, they were encouraged by my mother — even though

I

hated them at first. In defiance and frustration, I would sometimes get up from the piano and, groping for the nearest wall, place my hands on it, palms flat, and repeatedly bang it with my head. The white keys were impossible. The black notes stood out from the keyboard, and I could feel them and distinguish them from the whites. But that endless row of seemingly identical keys stretching from Mongolia to the Cape of Good Hope? Impossible. There are blind pianists (not very good ones) who play only in F sharp, B, and D flat because there are five black keyboard notes in each of those tonalities. A showboat blind pianist like George Shearing can reach out suddenly with his right hand and plink a G above high C, unerringly true and clean and hard, but that’s a very difficult thing to do, believe me, even for men who can see.

I

hated them at first. In defiance and frustration, I would sometimes get up from the piano and, groping for the nearest wall, place my hands on it, palms flat, and repeatedly bang it with my head. The white keys were impossible. The black notes stood out from the keyboard, and I could feel them and distinguish them from the whites. But that endless row of seemingly identical keys stretching from Mongolia to the Cape of Good Hope? Impossible. There are blind pianists (not very good ones) who play only in F sharp, B, and D flat because there are five black keyboard notes in each of those tonalities. A showboat blind pianist like George Shearing can reach out suddenly with his right hand and plink a G above high C, unerringly true and clean and hard, but that’s a very difficult thing to do, believe me, even for men who can see.

I worked like a dog memorizing that keyboard and the major scales, Miss Goodbody drumming intervals into my head and teaching me to play simple five-note pieces in different keys, accompanying them with basic chords, identifying the chords for me. My repertoire of chords was limited in the beginning to the tonic, the dominant seventh, and the subdominant, but I learned to identify and to play these in all the keys. (Miss Goodbody, I’ve since learned, was somewhat advanced for her time, in that she believed a person could not play intelligently or feelingly unless he knew what was happening harmonically.) Rhythm was a serious problem. I could

hear

the rhythm as well as any sighted person, but conceptualizing a “quarter note” or “four eighth notes” without being able to

see

those notes was enormously difficult. Miss Goodbody helped me with this by singing out the values of the notes. “Quarter, quarter, eighth, eighth, eighth, eighth,” simultaneously clapping her hands in tempo. By the time I was ready to begin reading Braille music, Miss Goodbody had acquainted me with the entire keyboard, encouraging me to play with “big” motions, forcing me to move out of a habit I’d had in the beginning (clinging to that middle C for dear life, my thumb firmly rooted on it), and teaching me to identify the major, minor, diminished, and augmented triads in all twelve keys.

hear

the rhythm as well as any sighted person, but conceptualizing a “quarter note” or “four eighth notes” without being able to

see

those notes was enormously difficult. Miss Goodbody helped me with this by singing out the values of the notes. “Quarter, quarter, eighth, eighth, eighth, eighth,” simultaneously clapping her hands in tempo. By the time I was ready to begin reading Braille music, Miss Goodbody had acquainted me with the entire keyboard, encouraging me to play with “big” motions, forcing me to move out of a habit I’d had in the beginning (clinging to that middle C for dear life, my thumb firmly rooted on it), and teaching me to identify the major, minor, diminished, and augmented triads in all twelve keys.

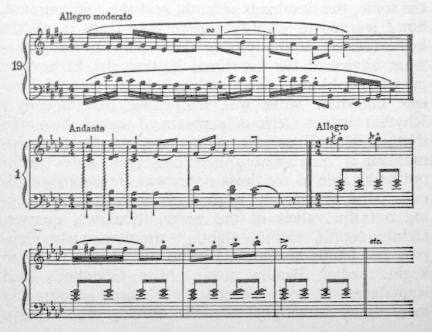

I should explain that Braille musical notation is rather complicated, and involves a great deal more than simply embossing or raising a

sighted

person’s music so that it can be felt by the blind. To begin with, the bass clef and the treble clef are not normally indicated in Braille music. Instead, the keyboard is divided into seven octaves starting with the lowest C on the piano, and using each successive C as a reference point. When Miss Goodbody was identifying a specific note, she would say, “That’s a second-octave D,” or “No, Iggie, you’re looking for a sixth-octave G.” I’d been having enough trouble learning to read

regular

Braille, and now I was presented with an entirely

new

language — just as music for the sighted is a language quite different from English or Bantu. To give you some idea, this is what a simple exercise would look like in European notation:

sighted

person’s music so that it can be felt by the blind. To begin with, the bass clef and the treble clef are not normally indicated in Braille music. Instead, the keyboard is divided into seven octaves starting with the lowest C on the piano, and using each successive C as a reference point. When Miss Goodbody was identifying a specific note, she would say, “That’s a second-octave D,” or “No, Iggie, you’re looking for a sixth-octave G.” I’d been having enough trouble learning to read

regular

Braille, and now I was presented with an entirely

new

language — just as music for the sighted is a language quite different from English or Bantu. To give you some idea, this is what a simple exercise would look like in European notation:

Other books

Quinn by Ryan, R.C.

All's Well That Ends by Gillian Roberts

Evil Behind That Door by Barbara Fradkin

Taken: The MISTAKEN Series Complete Third Season by Peak, Renna

Solitaire, Part 3 of 3 by Alice Oseman

The Time of the Ghost by Diana Wynne Jones

Second Chances by McKay, Kimberly

Kelly's Quest (NYC LOVE Book 2) by Ann, Jennifer