Stress: How to De-Stress without Doing Less (14 page)

Read Stress: How to De-Stress without Doing Less Online

Authors: Kate Middleton

The third question is about sleep. Sleep is a very valuable and elusive commodity for many of us, particularly those who juggle family with work and other demands. So,

roughly how many hours of sleep do you get each night?

Sleep is very important and very few of us get enough! Some interruptions to sleep are unavoidable (for example, young children) but do be aware that getting too little sleep will take its toll, so you need to try to counteract lack of sleep by putting in place some time somewhere in your day when you

can relax and recuperate. Meanwhile, if you know that you are scrimping on sleep time because you are too busy, or if you are having trouble sleeping, do something about it! (See Chapter 17 for more on this.)

This is just the start of making some changes to your lifestyle and weekly timetable in order to make sure you are dealing with stress in the best way possible. Hopefully this exercise will have made you more aware of some areas you might need to work on. Suffering because of stress is not a sign of weakness. It is just a sign of being human. So, if it turns out that you, like me, are only human, try not to get caught up in an unhelpful coping strategy â something that will make things worse in the long term rather than better. Instead, put in place some space in which you can recover from the stress that life so often throws your way, deal with the boundaries and make sure that you keep some precious time for you.

So far we've been on a journey of starting to understand what stress is and how it affects us specifically. Hopefully, after keeping your lifestyle diary for a couple of weeks, you will have identified some areas in your life that may need attention. That, combined with the information you'll read in the next two chapters about introducing relaxation (âdown') time into your schedule, will help you to start to make some serious changes to the impact stress has on you. But what about those of us who are experiencing more stress than it seems we should in the circumstances in which we're living? What if you feel you are not doing very much but are still struggling with experiencing a lot of stress? What if the chapters in part 2 have led you to suspect that there are some things about you and the way you approach life that may be making you much more vulnerable to stress than other people? Again and again research shows that individual factors such as personality and thinking styles can make all the difference in how much stress we experience. So, how do you start to look at the way you approach the world, and how do you change things about the way you think? This chapter will look at an exercise that will help you to start to become more aware of what is going on in your thoughts and emotional life when you are stressed.

Keeping a thought diary

This exercise involves keeping what is called a thought diary.

Thought diaries are all about looking consciously at thought patterns that would usually be automatic. Did you know that you are talking to yourself all the time? Some of us are more aware of our âinternal dialogue' than others, but we all do it! Thought diaries ask you to write down what your thoughts are at particular moments of the day.

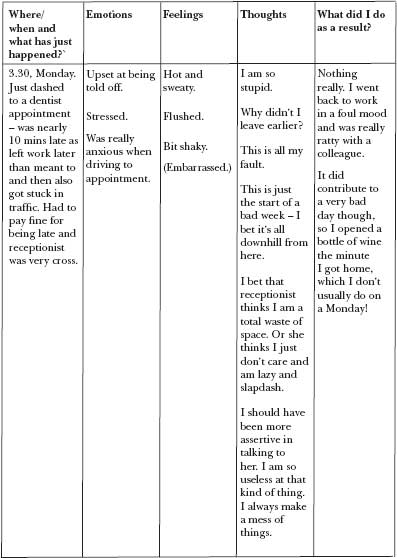

When you are starting to investigate your own stress reactions, the best thing to do is fill out the diary each time you would say that you are feeling stressed. You can do this in the heat of the moment if that is possible, or fill it out at the end of each day, thinking back through the day to the times when you were stressed. Each time fill out the diary as follows (you can see an example in figure 14).

Start by noting the

time of day

you were feeling stressed and

what had just happened

. This is important because you might be looking for patterns in what triggers stress and because you want to know what you were reacting to. Next, write down

what emotions you are experiencing

and then

what you are feeling physically

. These two steps are important because sometimes we get so used to our emotional reactions that we don't even notice them. We notice feeling âstressed' but don't pick up on the fact that it is because we are feeling anxious. Taking the time to ask yourself what emotions you are experiencing can help alert you to something like this, or you might notice that you are writing down the physical symptoms of an emotion like anxiety even though you are not aware of being anxious. The other reason this is important is because of the link between physical things and stress. You may note down something like âhaving a lot of pain from my back' or âhave bad headache'. These kind of things over time might prove to have a regular pattern â perhaps because stress is triggering headaches you had blamed on something

else, or because you are much more prone to reacting badly to something if a chronically painful condition is giving you problems.

1

The next step in the thought diary is to

list the thoughts that are running through your mind

. Try to delve behind each one to see if something else is behind it that you are less aware of. You might write, âI really mustn't be late for this appointment,' and miss the thought that lies behind it: âWhat will they think of me if I am late? They might think I am incompetent!' Do practise this, and don't worry if you find it hard at first. Some people find it helps to think of their mind as a radio and to write down everything that is coming out of the speaker. Try not to censor what you are writing. It might be hard to put thoughts down on paper but you will get the best out of this if you are honest! You might also be surprised or even shocked to find yourself thinking some things. Don't judge the thoughts â just write them down! The interpretation stage follows on, but you won't be able to do it well if you haven't written down what you were really thinking!

Finally, note down in a final column

what you did as a result of what you were feeling

. This is very helpful as it might identify if you are reacting in ways that are unhelpful. You might even surprise yourself as you come to recognize what makes you do some of the things you do. Or you might realize that you do not do much in order to respond to your emotions. So where do they go? This might help you identify that you are at risk of not expressing your emotions, which makes you more likely to be suppressing them and which in the long term makes stress worse rather than better. This column can also be very helpful in the next stage when you are looking at introducing some more helpful responses into your life in those moments when stress takes hold.

Â

Figure 14: Example of a thought diary

The best thing to do is to fill out this diary each time you have an episode of feeling stressed over a period of a few weeks. From that you should have a set of diaries which you can then start to look at and take some time to analyse what you are thinking and feeling. Do remember, though, that it might take you some time to get used to filling out the diary, so don't rush yourself.

Once you have a reasonable number of examples in your diary, you can start to look more closely at the patterns in your thinking and in your experience. You might want to ask yourself the following questions:

Am I prone to any unhelpful thinking styles?

Look through the lists of thoughts, and note down examples of unhelpful thinking as listed in Chapter 10. You might want to get a highlighter in a different colour for each one, and highlight any thoughts that are an example of that. There are a number of examples in figure 13. âI am so stupid' is an example of emotional reasoning (you may feel stupid but that doesn't mean you definitely are), whereas âThis is just the start of a bad week â I bet it's all downhill from here' is an example of negative thinking (making negative predictions about the rest of the day and week based on one unfortunate event). The key with identifying these unhelpful patterns is to become more aware of when you are slipping into them. You will find over time that you notice yourself thinking in these ways in the moment, as it is happening. You might even be able to catch yourself and stop the thought before it comes out. It is important to realize that although it felt as if that thought was true, it probably isn't as bad as you thought.

Are there any rules or goals that I live by that are causing problems?

Over time, as you keep an eye on your

thoughts, you may find certain thoughts come up again and again. Often these will be examples of the unhelpful thinking styles, and it is almost as if they lie in the background, waiting for a chance to pop up and make you feel bad again! Some of these may have obvious roots in your past, but it may be more difficult to work out where others come from. One person I worked with found that time and time again the thought âI am such a failure' came up in her thought diary. It happened in all kinds of scenarios, sometimes triggered by obvious things such as when she had messed something up, but sometimes occurring almost at random in circumstances when she would have expected to feel fine, such as when out with friends or when cleaning the house. If you identify a thought like that, it is very possible that this is linked to some kind of base belief you hold about yourself or about the world. Finding that belief is a bit like trying to reach down into the earth to find the root of a weed. This process is about looking through your thought âgarden' and trying to clear out any weeds.

I tend to use what I call the âSo what?' approach to do this. It goes something like this. You say (or write down) the thought to yourself. Then ask yourself, âSo what?' Try to answer quickly and instinctively â it's your gut reaction we want to access, not your more thought-through ârationalized' thoughts. Keep asking âSo what?' until it feels as if you cannot go any further: you have got to the root. So, for the example above â âI am such a failure' â you might go through a process like this:

âI am such a failure.'

SO WHAT?

âI always mess things up.'

SO WHAT?

âI'm always letting people down.'

SO WHAT?

âI should never let people down.'

SO WHAT?

âI should always be able to live up to what other people expect of me.'

SO WHAT?

âI should be a better person.'

Do you see how this process is starting to get from the thought âI am such a failure' down to the rules that are at the root of it? In this case there are two beliefs that seem to be related to this thought â something about being able to be what other people expect and never let them down, and something about being âa better person', someone who achieves very highly. The chances are that if you repeat this exercise with a few thoughts that seem to recur, you will find that some of them grow from the same root.

Of course, this exercise might bring out other things for you. You might notice certain patterns about when you feel stressed. Is it linked very much to certain people, for example? Or you might notice a link between your own stress and the way you respond. Perhaps you are more prone

to being ratty or impatient when you are stressed. You might notice that you are not responding in a very positive way to stress (more about the right way to respond in the next chapter!). Hopefully, you will find this exercise a positive experience. It might be daunting seeing our thoughts and feelings down on paper, but understanding why we are feeling that way helps us to feel less out of control â and to see that it all makes sense! And if it all makes sense, there must be a way to change things that we want to change. I have never worked with anyone where, after this exercise and knowing their background, I couldn't say that what they were feeling was totally logical. It wasn't necessarily helpful or correct, but it

was

logical. Remember that this exercise is about understanding better what is going on. Avoid being tempted to place blame: this is not an opportunity for you to have a go at yourself or anyone else. It is simply an exercise in describing what is going on so that you can then decide what to do.

A word of caution

Before I move on, it's important to mention that for some people this exercise is very hard. They may be experiencing really intense emotions or struggling with very painful experiences or memories. Sometimes this process can lead them to dwell on those things or to feel trapped by memories and emotions that are retriggered by the process. If this is you, please don't persist in trying to work it out on your own. Identifying problem thoughts and the beliefs at their root isn't always easy, and many people find that it helps to have someone else's perspective on things. Think about sharing your diary with a trusted friend (perhaps you could keep

diaries together and help each other to look at them), or go and get some expert help, either from your doctor or from a private counsellor. This isn't always something you can do on your own.

Whether you are working on your own or with someone else's support, once you have some idea of some of the thoughts that are troubling you, or the beliefs that are at their root, the next step is to start to challenge and question them. Understanding them has already stopped them simply being something automatic that you are unaware of. It gives you alternative options about how you might want to think or react. In fact, lots of us are living each day according to rules or beliefs that, if we thought about it, we don't even agree with! One quick test of this is to think about that rule/belief â for example, âI should always be able to please everyone all the time.' Think of someone you love or care about and ask yourself, âWould I teach that person to live according to this rule?' If the answer is âno', then this raises the interesting question of whether you want to keep pushing yourself to live according to it.

Reforming unhelpful thought patterns

A longer version of this challenging exercise is to sit down with a piece of paper and think about why you believe that thought. Perhaps think of some examples of when you felt it, then try to write down what it was about that situation that made you think that thought. Think of it as writing down the evidence FOR that thought. You might put down things that people have said, or things that have happened, or things you have felt. Then think about whether there is any evidence AGAINST. Sometimes just outside of that particular

emotionally charged moment we can see that actually things weren't so bad and the thought wasn't really accurate. Sometimes our friends and family actively disagree with the thought and we know they would challenge it. Try to think of any evidence against and then look at the overall picture you have â for and against. Your aim is to write down a more balanced conclusion. So you might write, âWhen I realized I had burned the potatoes last night at the dinner party, I felt as if I was totally useless and never got anything right. Part of that came from feeling guilty because I felt responsible for the people I had invited having a good evening. But now I realize that a lot of why I felt that way was because of the pressure I put myself under to get everything perfect. In fact, people did have a good time in spite of what happened and, even if they hadn't, burning one thing doesn't mean I am useless. I cooked all the rest of the meal really well and everyone enjoyed the evening on the whole.'