Stress: How to De-Stress without Doing Less (3 page)

Read Stress: How to De-Stress without Doing Less Online

Authors: Kate Middleton

Now that we know that stress is something real â and something that affects us physically as well as emotionally â it's important to know a bit about the specific kinds of impact that stress can have. Stress is blamed for all kinds of things, but what is the real evidence? What problems can stress cause, and what

kind

of stress is it that actually has these effects?

How the stress system is supposed to work

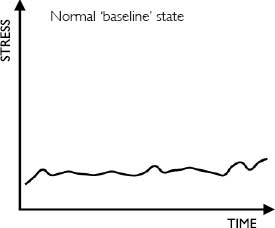

To understand better how stress can build up to a level that starts to cause problems, it's helpful first to look at how the stress system is supposed to work. Imagine for a minute that you were standing in a swimming pool, with most of the water drained out. We're going to use that image to represent the level of the various stress hormones in our body. Obviously it's a bit more complicated, but this image illustrates what happens when our stress levels start to rise. The water level is a bit like the level of all those stress hormones, and where it is now is the normal baseline level of your body's stress hormones â nice and low and very manageable (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Baseline level of stress

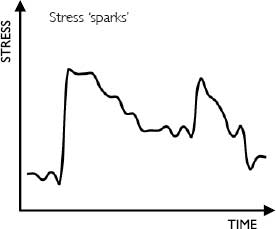

Now, most people agree that our body was designed to cope quite well with short-term (acute) stress. What happens then is that your brain triggers a response to the stress, which might look like a short spike on the graph (see figure 2). In our illustration this would be a bit like a wave in the swimming pool. Of course, with the water level at baseline, lapping calmly round your ankles, a wave isn't any problem and we cope with it just fine. Once the stress has resolved (remember it's only a momentary thing), hormone levels

gradually come down again and very soon we are back at baseline. This pattern, with natural spikes that then die back down to normal, is quite healthy and unlikely to cause any problems. Normal everyday stresses which need us to respond happen quite naturally, and we even have the capacity to cope with something more major should it happen and keep on functioning just fine.

Figure 2: Acute stress âsparks'

What happens when stress starts to build?

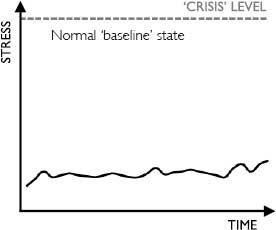

On the whole, trouble with stress starts when this natural rhythm of the system is interrupted. If you go back to the image of yourself standing in the swimming pool, you can imagine that the natural waves caused by stress spikes are fine if the water level is quite low, but there would be a âcrisis level' where, if the water were always that high, waves would start to be a real problem â the water could reach the kinds of levels where you might start to feel you were going under (see figure 3).

Figure 3: The âcrisis' level of stress

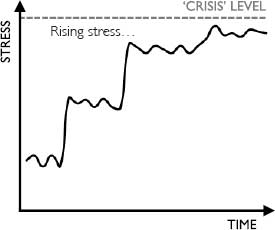

Two things can cause this to happen where stress is concerned. Remember that it takes some time for hormone levels to drop back down to baseline. If we are experiencing so much stress â that is, life is throwing so much at us that the next âspike' happens before the last one resolves â the levels can easily start to get near to that crisis line (see figure 4). Most of us will have experienced days (or weeks!) like this, when one thing seems to come after another. Those are the days when one small thing at the end of the day can cause us to fly off the handle apparently irrationally. We come home and our partner asks us what's for dinner, and that question pushes us into an enormous rage as we feel totally overwhelmed by the unfair responsibility they expect us to shoulder. Or we drop a mug, and for some reason it just feels like too much and leaves us on the edge of tears. With the water levels raised, even the normal stresses of everyday life feel as if they push us close to the edge, and we are likely to find ourselves craving peace and quiet and some time to recharge our batteries.

Figure 4: Stress builds up to dangerously near crisis level

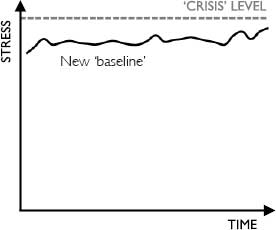

What we call ârecharging our batteries' is, of course, something that allows us to turn off the sympathetic system and chill out a bit, meaning that the water levels start to drop back down to our usual baseline. It is really important that this happens because it restores that natural âebb and flow' of the system. Unfortunately, however, this is often not what happens. If we do not have time to build in this rest and relaxation, if we are people who find relaxation challenging â or, of course, if the stresses bombarding us just keep on coming, then our system never gets this chance to âreset'. As a result, something very important happens: in effect, our baseline level of stress hormones becomes chronically raised (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Baseline stress levels can become chronically raised

So, why does this matter, and what does this feel like in real life?

You probably won't notice your baseline stress gradually rising until it gets too close to that crisis level. Then you suddenly find that you are existing

all the time

with much

higher water levels. You may well feel âon the edge' because your baseline stress has become so high that even something relatively minor can easily push you not just into a difficult position but into a place where you risk a real crisis.

One person I have worked with is a typical example of this kind of pattern. He is a normal guy, working in an normal job, in a commuter town just outside Greater London. He came to speak to me after his doctor had told him that a physical problem he was suffering from was related to the stress he was under. âThe thing is,' he said to me, âI just don't feel as if I am under that much stress. It's not as if I am a nuclear scientist, or a policeman, or anything like that. In fact, day by day I don't really find that the things I am facing are that stressful. But if I'm honest, I do feel on the edge. It's as if suddenly things that wouldn't have bothered me a few years ago have become big deals. So, if the kids are being difficult, I just can't handle it as well as I used to, and I am getting these thoughts flashing through my head about needing to escape or get away. I feel as if I'm constantly at the edge of my capacity to cope with whatever gets thrown at me, and it's a really uncomfortable feeling. I can't relax and now I am having trouble sleeping, which is making things even worse. I feel really weird because I don't see why I should have a problem, but, if I'm honest, it's starting to get scary because I don't know how to get out of feeling like this.'

This is an uncomfortable way to live life, and if this is you right now, you will be feeling pretty horribly aware of how stressed out you are. This kind of chronic rise in stress levels is very important because our body simply wasn't designed to exist under these kinds of conditions. As we'll see in the next chapter, if our body is exposed continually to raised

levels of the stress hormones, it will have some physical and emotional impact on us, whether we are aware of it or not. Many of the physical effects in particular are things that build up over time, so it may be a long-term concern rather than something that we will notice right now. But, to be honest, most people know when they are living in this state, and it's not at all unusual.

In fact, twenty-first-century life can very easily push us into living with the kind of continual stress that can build up to this point. Many of us are living lives jam-packed with activities â be those work (as many of us work ever longer hours), family (just try getting a few children up, ready for school and out of the house on time five days a week!), relationship stresses, studying of some kind (many school children are now just as stressed out as their parents) or so-called leisure time (âwork hard, play hard' might be fun, but it often isn't relaxing and can leave us totally exhausted as we try to pack too much in). Often it isn't that life is full of stress spikes, just that the general pace of life is so frantic that it becomes constant and consistently stressful, leaving little or no time for the vital relaxation which would restore the system back to baseline.

A woman I worked with explained to me the things that she felt were behind her own problems with stress. âI know I am stressed-out a lot of the time,' she said, âbut I don't see what I can do about it. People always say I should do less or relax more â but when? If it's not getting the kids to school on time (which is always a nightmare), I am frantically cleaning, or cooking, or making costumes, or whatever the latest thing is they need. I've had to take on a part-time job to try to help bring some extra money in and that's really stressful because I'm constantly trying to work out how I can fit in the things I need to do for work around the edges

of the things my kids need. I seem to spend most of my time feeling guilty. If I am working, I feel guilty and worry that my children need me, but if I am at home, I often am so aware of work that needs doing and I feel guilty for not doing that. I feel as if I am literally being pulled in several different directions and I am just not able to keep up with all the things I am supposed to be doing.'

Stressful events in life

For some of us, of course, the kind of stresses we are facing are not down to choices we have made. Life can throw things at us, and very often it seems to be totally unfair as lots of things all happen at once. Life events such as the death of someone close to us, moving house or even happy things that involve major changes to our life, such as getting married or leaving home, all trigger stress. In the late 1960s, a couple of psychiatrists worked through their notes on thousands of their patients and put together a list of stressful events that seemed to be linked to the chances of stress triggering illness in the people they were working with. The scale, which they then went on to test, gave each event a score. The idea was that you added up the total from each event you had experienced in the last year and this could give you an idea of the levels of stress you were under. Scores over about 150 seemed to indicate that you might be at risk of your stress causing you problems; at scores over 300 this was even more marked. You can see a list of some of the events and their scores in figure 6, overleaf.