Takeoff! (2 page)

Authors: Randall Garrett

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Science Fiction; American, #Parodies

I showed up, but I have the feeling that Van was far more impressed by the blue-eyed ‘honey blonde I brought with me.

Van’s working out of my age is a marvel of mathematical exactitude. I

was

born in 1927. Unlike Bilbo, I have never liked birthday parties, especially my own. Just for the novelty, I decided to celebrate my fiftieth, but only after it had passed;

You are all invited to my next such party, to be held sometime after my eleventy-first birthday.

By that time, I may have enough material to put together another book like this, but that is problematical. You see, I only do them when I bloody well feel like it. If the right idea for a pastiche or parody hits me, I do it, but that doesn’t happen often. This book represents some twenty years of that kind of work.

The difference between a pastiche and a parody is, perhaps, a subtle one..

A pastiche attempts to tell a story in

the

same

way

that another author would have told it. In this book,

The Best

Policy is a pastiche, not a parody. I used, to the best of my ability, Eric Frank Russell’s style of writing and his way of telling a story.

A parody, when properly done, takes an author’s idiosyncrasies—of style, content, and method of presentation—and very carefully exaggerates them. You jack them up just

one more notch.

The idea is to make those idiosyncrasies

blatantly

visible. Thus,

Backstage Lensman

is a parody. Doc Smith would never have-very probably

could

never have-written it. It is very difficult indeed for a writer to see his own idiosyncrasies; they are too much a part of him.

But the line between parody and pastiche is not hard and thin; it is broad and fuzzy. Is

The

Horror

Out

of

Time

a pastiche or a parody? I don’t know. You tell me.

I do not decide to write a pastiche or parody just for the sake of writing one. The story idea comes first. In 99.44% of the cases, I write my own story in one of my own styles. But once in a very great while it seems to me that the idea belongs in someone else’s universe. Then I write a pastiche. See, herein, No

Connections.

And when the idea belongs in another’s universe—except that it is patently ridiculous—I write a parody. The idea for

Backstage

Lensman, for instance, you will find in the next-to-last scene, in a simple mathematical formula. All the rest of it came from that.

The “Reviews in Verse” are a different breed of mutant. They are quite deliberate. The idea is to tell the plot with reasonable accuracy—and

leave out the entire point that the author was trying

to

make!

So even if you do not heed my warning at the beginning of that section, you will still not know what the story is really about. For that, go to the originals.

The “Little Willies” are takeoffs of an Englishman named Harry Graham, who originated them. Since he was a retired officer of Her Majesty’s [Victoria, that is.] Coldstream Guards, he wrote under the name

“Col. D. Streamer.”

The Benedict Breadfruit stories need no introduction from me. My very good friend, Reginald Bretnor, got

his

very good friend, Grendel Briarton, to do an introduction for them. And Mr. Briarton, apparently, had to go to Ferdinand Feghoot for the final copy.

I have not, by any means, given what might be called The Garrett Treatment to

all

the writers I admire. Although Van’s

Slan

is in here, his distinctive style is ripe for story treatment. Ted Sturgeon would be fun. Fritz Leiber is on my little list. Bob Silverberg is begging for it. Lester del Rey is going to get his one of these days. Cordwainer Smith has it coming. Frank Herbert will not go unscathed. Mack Reynolds is overdue. Avram Davidson will not be neglected. Neither will Michael Kurland. There are others. Just wait.

Maybe

before

my eleventy-first...

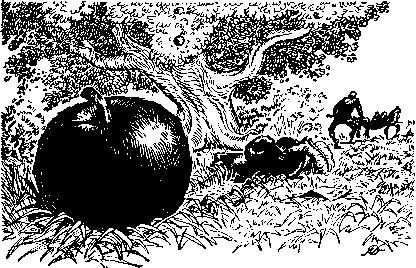

Wait! Don’t go away! This book is like a tapestry. I supplied the basic material, and Frank Kelly Freas supplied the lovely embroidery. [Is that a crewel remark?] When this book becomes an expensive collector’s item (when. not

if

). it will be because of Kelly’s work, not mine.

(Kelly, if you or Polly cut what follows because of some false feeling of modesty, may your pencils break, your inkpots run dry, your typewriter clog, your paints become gelatinous, and your canvas rot. Truth, dammit, is truth!)

This book is Kelly’s work in more than one way. Let me give you some background, and then I’ll tell you a true story.

I met Kelly in the early fifties at a science fiction convention. I don’t remember which one; they all begin to blend into one another after all this time. (See, Van? I told you!) I don’t remember the con, but I remember Kelly. At that time, he sported a large red mustache and a smile which kept it turned up at the ends. I loved the man immediately.

Kelly is witty, outgoing, friendly, gregarious, and articulate. He is shrewd, careful, intelligent, and analytical. He is sensitive, understanding, warm and compassionate. And he knows the science and technique of art as few people in history have known it.

He is, of course, a science fiction fan of the highest caliber. It shows in every illustration he does. He cares about science fiction. And he cares about the people who write and read it.

That’s not all the background I could give you on the man, but it will have to do for the nonce. Now comes the story.

A while back, I was talking to Kelly on the phone about a book of mine that didn’t quite measure up to his and Polly’s specifications. Suddenly, he said: “Hey! What about a book of your parodies and pastiches?”

“Is the world ready for this?” I asked.

“Damn right it is!” and he mentioned several stories he liked. He got me enthusiastic, and I went to work finding them.

About a week later he called me.

“I’ve

got

it! I’ve

got

it!”

he shouted into my tender ear.

Carefully easing the receiver back toward that offended organ, I

said: “you do? Is it contagious?”

“No, no! I’ve got the title for your book!”

Nero Wolfe once said: “I have no talent. I have genius or nothing.” The thing about Kelly is that he has

both.

His talent lies in his ability to use any and every artistic medium that exists. His genius lies in the

way

he uses them. And that genius shows through every medium.

Let me give you an imaginative example-what Albert Einstein called a “thought experiment.”

I am fond of churches as works of art; I am a church buff, among other things, and I go absolutely ape over the Gothic style. The great Gothic cathedrals of Europe really turn me on, and if I were going to build a church, it would be in that style. Suppose I had enough money to build the church of my dreams. It would take many tens of millions of dollars today.

With that vast sum in my pocket, I would go to Frank Kelly Freas and say: “Kelly, build me that church. Hire engineers, hire architects, hire artisans of any kind you need. Money is no object, but build me that church.”

He could do it; you damn well betcha he could. The spires, the gargoyles, the statues, the stained glass windows-all. And when he was through (assuming a lifespan of some three centuries), it would be the most beautiful church in all Christendom. That is his talent.

And those who know his genius would take one look at it and say, in no irreverent tone: “My God!

That’s a Frank Kelly Freas Church!”

Selah.

GENTLEMEN: PLEASE NOTE

By Randall Garrett

This might be considered an “alternate history” story, and in

a

way, I suppose

it

is. But not in the sense that, say, the Lord Darcy stories are. This is a takeoff, not on history, but on the way certain self-important know-it-alls do their best to put down the gifted person just because his notions don’t agree with theirs. And, far too often, they succeed.

This is a study in “how to stomp on the crackpot.”

With the exception of General B-f, all the characters

mentioned

in this story were actual historical persons, but, with the possible exception of King Charles II, were nothing like I have depicted them.

My

apologies especially to Isaac Barrow, who, as far as my historical reading has led me to believe, was a much nicer guy.

18 June 1957

Trinity College

Cambridge

Sir James Trowbridge

No.14 Berkeley Mews

London

My dear James,

I’m sorry to have lost touch with you over the past few years; we haven’t seen each other since the French War, back in 1948. Nine years! It doesn’t seem it.

I’ll tell you right off I want a favour of you. (No, I do

not

want to borrow another five shillings! I haven’t had my pocket picked again, thank you. ) This has to do with a little historical research I’m doing here. I stumbled across something rather queer, and I’m hoping you can help me with it.

I am enclosing copies of some old letters received by Isaac Newton nearly three hundred years ago. As you will notice, they are addressed to “Mr. Isaac Newton, A.B.”; it rings oddly on the ear to hear the great man addressed as anything but “your Grace,” but of course he was only a young man at the time. He hadn’t written his famous

Principia

yet—and wouldn’t for twenty years.

Reading these letters is somewhat like listening to a conversation when only one of the speakers is audible, but they seem to indicate another side to the man, one which has not heretofore been brought to light.

Dr. Henry Blake, the mathematician, has looked them over, and he feels that it is possible that Newton stumbled on something that modern thought has only recently come up with-the gravitational and light theories of the Swiss mathematician, Albert Einstein.

I know it’s fantastic to think that a man of even Newton’s acknowledged genius could have conceived of such things three centuries before their proper place in history, but Blake says it’s possible. And if it is, Blake himself will probably do to Newton’s correspondents the same thing that was done to Oliver Cromwell at the beginning of the Restoration—disinter the bodies and have them publicly hanged or some such thing.

Actually, Blake has managed to infect me with his excitement; he has pointed out phrases in several of the letters which tally very well with Einstein’s theory. But, alas, the information we have is woefully incomplete.

What we need, you see, are Newton’s letters—the ones he sent which provoked these answers. We have searched through everything here at Cambridge, and we haven’t found even a trace; evidently the Newton manuscripts were simply discarded on the basis that they were worthless, anyway. Besides, records of that sort were poorly kept at that time.

But we thought perhaps the War Office did a somewhat better job of record-keeping.

Now, I realise full well that, due to the present trouble with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the War Office can’t take a chance and allow just anyone to prowl through their files. It wouldn’t do to allow one of the Emperor’s spies to have a look at them. However, I wondered if it wouldn’t be possible for you to use your connexions and influence at the War Office to look for Newton’s letters to one of the correspondents, General Sir Edward Ballister-ffoulkes. You can find the approximate dates by checking the datelines on the copies I am sending you.

The manuscripts are arranged in chronological order, just as they were received by Newton himself. Of them all, only the last one, as you will see, is perfectly clear and understandable in all its implications.

Let me know what can be done, will you, old friend?

With best wishes,

SAM

Dr. Samuel Hackett

Department of History

12 November 1666

London

Mr. Isaac Newton, A.B.

Woolsthorpe

Dear Mr. Newton:

It was very good of you to offer your services to His Majesty’s Government at this time. The situation on the Continent, while not dangerous in the extreme, is certainly capable of becoming so.

Your letter was naturally referred to me, since no one else at the War Office would have any need for the services of a trained mathematician.

According to your précis, you have done most of your work in geometry and algebra. I feel that these fields may be precisely what are needed in our programme, and, although you have had no experience, your record at Trinity College is certainly good enough to warrant our using your services.

If you will fill in the enclosed application blank, along with the proper recommendations and endorsements, we can put you to work immediately.

Sincerely,

Edward Ballister-ffoulkes, Bart.

General of Artillery

Ballistics Research Dept.

12 November 1666