The Annotated Lolita: Revised and Updated (10 page)

Read The Annotated Lolita: Revised and Updated Online

Authors: Vladimir Nabokov

The parodic references to R. L. Stevenson suggest that Nabokov had in

mind Henry Jekyll’s painfully earnest discovery of the “truth” that “man is not only one, but truly two. I say two, because the state of my own knowledge does not pass beyond that point. Others will follow, others will outstrip me on the same lines.” The “serial selves” of

Pale Fire

“outstrip” Stevenson and a good many other writers, and rather than undermining Humbert’s guilt, the Double parody in

Lolita

locks Humbert within that prison of mirrors where the “real self” and its masks blend into one another, the refracted outlines of good and evil becoming terrifyingly confused.

Humbert’s search for the whereabouts and identity of Detective Trapp (Quilty) invites the reader to wend his way through a labyrinth of clues in order to solve this mystery, a process which both parallels and parodies the Poe “tale of ratiocination.” When Humbert finds Lolita and presses her for her abductor’s name,

She said really it was useless, she would never tell, but on the other hand, after all—“Do you really want to know who it was? Well it was—”

And softly, confidentially, arching her thin eyebrows and puckering her parched lips, she emitted, a little mockingly, somewhat fastidiously, not untenderly, in a kind of muted whistle, the name that the astute reader has guessed long ago.

Waterproof. Why did a flash from Hourglass Lake cross my consciousness? I, too, had known it, without knowing it, all along. There was no shock, no surprise. Quietly the fusion took place, and everything fell into order, into the pattern of branches that I have woven throughout this memoir with the express purpose of having the ripe fruit fall at the right moment; yes, with the express and perverse purpose of rendering—she was talking but I sat melting in my golden peace—of rendering that golden and monstrous peace through the satisfaction of logical recognition, which my most inimical reader should experience now. (

p2.c29.1

.)

Even here Humbert withholds Quilty’s identity, though the “astute reader” may recognize that “Waterproof” is a clue which leads back to an early scene at the lake, in which Charlotte had said that Humbert’s watch was waterproof and Jean Farlow had alluded to Quilty’s Uncle Ivor (by his first name only), and then had almost mentioned Clare Quilty by name: Ivor “

told me a completely indecent story about his nephew. It appears—

” But she is interrupted and the chapter ends. This teasing exercise

in ratiocination—“peace” indeed!—is the detective trap, another parody of the reader’s assumptions and expectations, as though even the most astute reader could ever fully discover the identity of Quilty, Humbert, or of himself.

Provided with Quilty’s name, Humbert now makes his way to Pavor Manor, that latter-day House of Usher on Grimm Road, where the extended and variegated parodies of Poe are laid to rest. All the novel’s parodic themes are concluded in this chapter. Its importance is telescoped by Humbert’s conclusion: “

This, I said to myself, was the end of the ingenious play staged for me by Quilty.

” In form, of course, this bravura set piece is not a play; but, as a summary parodic commentary on the main action, it does function in the manner of an Elizabethan play-within-the-play, and its “staging” underscores once more the game-element central to the book.

Simultaneous with these games is a fully novelistic process that shows Humbert traveling much further than the 27,000 miles he and Lolita literally traverse. Foolish John Ray describes Humbert’s as “

a tragic tale tending unswervingly to nothing less than a moral apotheosis

” and, amazingly enough, he turns out to be right. The reader sees Humbert move beyond his obsessional passion to a not altogether straightforward declaration of genuine love (

here

) and, finally, to a realization of the loss suffered not by him but by Lolita (

here

). It is expressed on the next to the last page in a long and eloquent passage that, for the first time in the novel, is in no way undercut by parody or qualified by irony. Midway through this “

last mirage of wonder and hopelessness

,” the reader is invoked again, because Humbert’s moral apotheosis, so uniquely straightforward, constitutes the end game and Nabokov’s final

trompe-l’oeil

. If the reader has long since decided that there is no “moral reality” in the novel, and in his sophisticated way has accepted that, he may well miss this unexpected move in the farthest corner of the board and lose the game after all. It is the last time the reader will be addressed directly, for the game is about over, as is the novel.

In addition to sustaining the game-element, the authorial patterning reminds us that

Lolita

is but one part of that universe of fiction arrayed around the consciousness of Nabokov, who would join Humbert in his lament that words do indeed have their limitations, and that “the past is the past”; to live in it, as Humbert tried, is to die. That the author of

Speak, Memory

should suggest this surely establishes the moral dimension of

Lolita; and in the light of Johan Huizinga’s remark that “play is outside the range of good and bad,”

32

Lolita

becomes an even more extraordinary achievement.

When in

The Gift

Nabokov writes of Fyodor’s poem, “At the same time he had to take great pains not to lose either his control of the game, or the viewpoint of the plaything,” he is defining the difficulties he faced in writing novels whose full meaning depends on the reader’s having a spatial view of the book. It should be evident by now how the parody and patterning create the distance necessary for a clear view of the “plaything,” and Nabokov reinforces one’s sense of the novel-as-gameboard by having an actual game in progress within

Lolita

: the seemingly continuous match between Humbert and Gaston Godin—a localized, foreground action which in turn telescopes both the Humbert-Quilty “Double game” being played back and forth across the gameboard of America and the overriding contest waged above the novel, between the author and the reader.

33

Humbert

and Gaston play chess “two or three times weekly” in Humbert’s study, and several times Nabokov carefully links Lolita with the Queen in their game (

here

). One evening while they are playing, Humbert gets a telephone call from Lolita’s music teacher informing him that Lolita has again missed her lesson, the boldest lie he has caught her in, indicating that he is soon to lose her:

As the reader may well imagine, my faculties were now impaired, and a move or two later, with Gaston to play, I noticed through the film of my general distress that he could collect my queen; he noticed it too, but thinking it might be a trap on the part of his tricky opponent, he demurred for quite a minute, and puffed and wheezed, and shook his jowls, and even shot furtive glances at me, and made hesitating half-thrusts with his pudgily bunched fingers—dying to take that juicy queen and not daring—and all of a sudden he swooped down upon it (who knows if it did not teach him certain later audacities?), and I spent a dreary hour in achieving a draw. (

p2.c13.1

).

In their respective ways, all the players want to capture “that juicy queen”: poor homosexual Gaston, quite literally; pornographer Quilty, for only one purpose; pervert and poet Humbert, in two ways, first carnally but then artistically, out of love; and the common reader, who would either rescue Lolita by judging and condemning Humbert, or else participate vicariously, which would make him of Quilty’s party—though there is every reason to think that the attentive reader will sooner or later share Humbert’s perspective: “

In my chess sessions with Gaston I saw the board as a square pool of limpid water with rare shells and stratagems rosily visible upon the smooth tessellated bottom, which to my confused adversary was all ooze and squid-cloud.

”

Humbert is being too modest at the outset of

Lolita

when he says “

it is only a game

,” for it is one in which everything on the board “breath[es] with life,” as Nabokov writes of the match between Luzhin and Turati in

The Defense

. Radical and dizzying shifts in focus are created in the reader’s mind as he oscillates between a sense that he is by turns confronting characters in a novel and pieces in a game—as if a telescope were being spun 360 degrees on its axis, allowing one to look alternately through one

end and then the other. The various “levels” of

Lolita

are of course not the New Criticism’s “levels of meaning,” for the telescopic and global views of the “plaything” should enable one to perceive these levels or dimensions as instantaneous—as though, to adapt freely an image used by Mary McCarthy to describe

Pale Fire

, one were looking down on three or more games being played simultaneously by two chess masters on several separate glass boards, each arranged successively above the other.

34

A first reading of

Lolita

rarely affords this limpid, multiform view, and for many reasons, the initially disarming and distractive quality of its ostensible subject being foremost. But the uniquely exhilarating experience of rereading it on its own terms derives from the discovery of a totally new book in place of the old, and the recognition that its habit of metamorphosis has happily described the course of one’s own perceptions. What Jorge Luis Borges says of Pierre Menard, author of the

Quixote

, surely holds for Vladimir Nabokov, the author of

Lolita

: he “has enriched, by means of a new technique, the halting and rudimentary art of reading.”

A

LFRED

A

PPEL

, J

R

.

Palo Alto, California

January 31, 1968

Wilmette, Illinois

May 21, 1990

1

New York, 1941, p. 93. Henceforth, page references will be placed in parentheses in the text, and pertain to the Vintage editions of Nabokov’s novels, interviews, and autobiography, and to the hardcover editions of his other work.

2

Brian Boyd’s

Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years

(Princeton, 1990), the first volume in an anticipated two-volume biography, is recommended.

3

John Updike, “Grandmaster Nabokov,”

New Republic

, CLI (September 26, 1964), 15. Reprinted in Updike’s

Assorted Prose

(New York, 1965).

4

Raymond Queneau,

Le Chiendent

(Paris, 1933), p. 294. The above translations are mine—A.A.

5

Ibid.

6

James Joyce,

Ulysses

(New York, 1961), p. 567.

7

Ibid

., p. 769.

8

Ibid

., p. 513.

9

J. L. Borges, “Partial Magic in the

Quixote

,” in

Labyrinths

(New York, 1964), p. 196. For an excellent analysis of involuted or self-reflexive fiction, see Robert Alter,

Partial Magic: The Novel as a Self-Conscious Genre

(Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1975).

10

See Nabokov’s article “

Lolita

and Mr. Girodias,”

Evergreen Review

, XI (February 1967), 37–41.

11

In a manner similar to Joyce’s, Nabokov four years later paid his respects to Prescott, though not by name, by having the assassin Gradus carefully read

The New York Times

: “A hack reviewer of new books for tourists, reviewing his own tour through Norway, said that the fjords were too famous to need (his) description, and that all Scandinavians loved flowers” (

Pale Fire

, p. 275). This was actually culled from the newspaper.

12

Also pointed out by Andrew Field, in

Nabokov: His Life in Art

(Boston, 1967), p. 325, and Carl R. Proffer,

Keys to Lolita

(Bloomington, 1968), p. 3.

13

New York, 1986.

14

One should remember that the story would have been read by a Russian émigré audience, notes Andrew Field, who quoted the same two passages in his own translation,

op. cit

., pp. 328–329. Strongly erotic (as opposed to pornographic) themes have been used “seriously” far more frequently by Russian writers than by their English and American counterparts. Field points to Dostoevsky (the suppressed chapter of

The Possessed

), Leskov, Sologub, Kuzmin, Rozanov, Kuprin, Pilnyak, Babel, and Bunin (

ibid

., p. 332).

15

And speaking specifically of the writing of

Lolita

, he says, “She was like the composition of a beautiful puzzle—its composition and its solution at the same time, since one is a mirror view of the other, depending on the way you look.”

16

Penelope Gilliatt, “Nabokov,”

Vogue

, No. 2170 (December 1966), p. 280.

17

Ibid

.

18

Anthony Burgess, “Poet and Pedant,”

The Spectator

, March 24, 1967, p. 336. Reprinted in

Urgent Copy

(New York, 1969).

19

A photograph of these drawings appears in

Time

, May 23, 1969, p. 83.

20

For several reminiscences of Nabokov, see

Vladimir Nabokov: A Tribute

, edited by Peter Quennell (New York, 1980).

21

In

Pale Fire

, Charles Kinbote spies John Shade seated in his car, “reading a tabloid newspaper which I had thought no poet would deign to touch” (p. 22).

22

The course in question is Literature 311–312, “Masterpieces of European Fiction,” MWF, 12 (first term: Jane Austen’s

Mansfield Park

, Gogol’s

Dead Souls

, Dickens’s

Bleak House

, Flaubert’s

Madame Bovary

, and Tolstoy’s

The Death of Ivan Ilyich;

second term: Tolstoy’s

Anna Karenina

, Stevenson’s

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

, Gogol’s

The Overcoat

, Kafka’s

The Metamorphosis

, Proust’s

Swann’s Way

, and

Ulysses

, in that order). The quotations are from the annotator’s class notes of 1953–1954 and can be supplemented now by Nabokov’s

Lectures on Literature

(New York, 1980).

23

Although published in New York in 1941, a year after Nabokov’s emigration,

The Real Life of Sebastian Knight

was in fact written in Paris in 1938 (in English). Students of chronology should also note that

Lolita

precedes

Pnin

(1957). The date of the former’s American publication (1958) has proved misleading.

24

For Nabokov’s later description of

posblost

(as he then transliterated it), see his

Paris Review

interview, collected in

Strong Opinions

(New York, 1973), pp. 100–101.

25

Satirized too is the romantic myth of the child, extending from Wordsworth to Salinger. “The McCoo girl?” responds Lolita kindly. “Ginny McCoo? Oh, she’s a fright. And mean. And lame. Nearly died of polio.” If the origin of modern sentimentality about the child’s innocence can be dated at 1760, with the publication of

Mother Goose’s Melodies

, then surely

Lolita

marks its death in 1955.

26

From the annotator’s class notes, 1953–1954.

27

Translated and quoted by Andrew Field,

op. cit

., p. 79.

28

Vladislav Khodasevich, “On Sirin” (1937), translated by Michael H. Walker, edited by Simon Karlinsky and Robert P. Hughes,

TriQuarterly

, No. 17 (Winter 1970).

29

I have elsewhere discussed the novel as a novel, as well as an artifice; see my article “

Lolita

: The Springboard of Parody,”

Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature

, VIII (Spring 1967), 204–241. Reprinted in L. S. Dembo, ed.,

Nabokov: The Man and His Work

(Madison, 1967).

30

See

frw.1

,

p1.c9.1

,

p1.c11.1

,

p1.c13.1

,

p1.c15.1

,

p1.c20.1

,

p1.c22.1

,

p1.c24.1

,

p1.c29.1

,

p1.c32.1

,

p1.c32.1

,

p2.c1.1

,

p2.c2.1

,

p2.c2.2

,

p2.c2.3

,

p2.c3.1

,

p2.c7.1

,

p2.c9.1

,

p2.c14.1

,

p2.c16.1

,

p2.c17.1

,

p2.c19.1

,

p2.c22.1

,

p2.c23.1

,

p2.c24.1

,

p2.c25.1

,

p2.c26.1

,

p2.c36.1

, and

p2.c36.1

—not to mention Humbert’s several interjections to the jury (

p1.c29.1

is typical), to mankind in general (“

Human beings, attend!

”), and to his car (“

Hi, Melmoth, thanks a lot, old fellow

”). One waxes statistical here because H.H.’s direct address is an important part of the narrative, and important too in the way that it demonstrates a paradoxically new technique. In regard to literary forms and devices, there is almost nothing new under the sun (to paraphrase a poet); it is contexts and combinations that are continually being made new. One epoch’s realism is another’s surrealism. To the Elizabethan playgoer or the reader of Cervantes, the work-within-the-work was a convention; to an audience accustomed to nineteenth-century realism, it is fantastic, perplexing, and strangely affecting. The same can be said of the reintroduction of “old-fashioned” direct address, revived and transmogrified at a moment in literary history when the post-Jamesian novelists seemed to have forever ruled out such self-conscious devices by refining the newer “impressionistic” conventions (the effaced narrator, the “central intelligence,” the consistent if “unreliable” narrative

persona

, and so forth). “This new technique is that of the deliberate anachronism,” writes J. L. Borges in “Pierre Menard, Author of the

Quixote

,” an essential text on the subject (

Labyrinths

, p. 44); and cinematic equivalents are readily available in the work of the directors who reintroduced silent film techniques (notably François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Richard Lester) in the 1950s and 1960s.

31

The pun is also pointed out by Page Stegner in

Escape into Aesthetics: The Art of Vladimir Nabokov

(New York, 1966), p. 104.

32

Johan Huizinga,

Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture

(Boston, 1955 [1st ed. 1944]), p. 11. An excellent introduction to Nabokov, even if he is not mentioned.

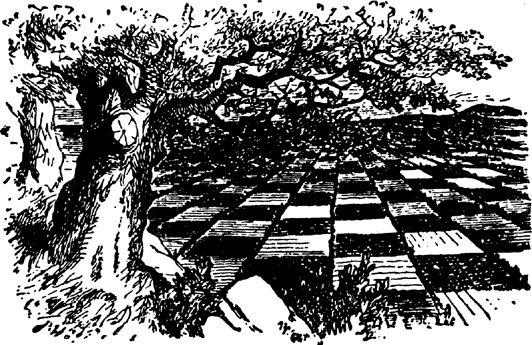

33

This aspect of

Lolita

is nicely visualized in Tenniel’s drawing of a landscaped chessboard (or chessbored landscape) for Chapter Two of Lewis Carroll’s

Through the Looking-Glass

, in which a chess game is literally woven into the narrative. For more on Carroll and Nabokov, see Note

A breeze from wonderland

.

34

Mary McCarthy, “Vladimir Nabokov’s

Pale Fire,” Encounter

, XIX (October 1962), p. 76.