The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (42 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Being incarcerated at the time of the interview signifies not just breaking the law and serving time but also something about the duration of the sentence, which may explain the large increase at the bottom of the ability distribution. The NLSY sample of white males echoes the scientific literature in general in showing a sizable IQ gap between offenders and nonoffenders at each level of involvement with the criminal justice system.

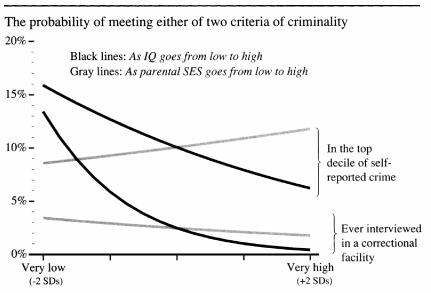

We will use both self-reports and whether the interviewee was incarcerated at the time of the interview as measures of criminal behavior. The self-reports are from the NLSY men in 1980, when they were still in their teens or just out of them. It combines reports of misdemeanors, drug offenses, property offenses, and violent offenses. Our definition of criminality here is that the man’s description of his own behavior put him in the top decile of frequency of self-reported criminal activity.

40

The other measure is whether the man was ever interviewed while being confined in a correctional facility between 1979 and 1990. When we run our standard analysis for these two different measures, we get the results in the next figure.

Both measures of criminality have weaknesses but different weaknesses. One relies on self-reports but has the virtue of including uncaught criminality; the other relies on the workings of the criminal justice system but has the virtue of identifying people who almost certainly have committed serious offenses. For both measures, after controlling

for IQ, the men’s socioeconomic background had little or nothing to do with crime. In the case of the self-report data, higher socioeconomic status was associated with

higher

reported crime after controlling for IQ. In the case of incarceration, the role of socioeconomic background was close to nil after controlling for IQ, and statistically insignificant. By either measure of crime, a low IQ was a significant risk factor.

On two diverse measures of crime, the importance of IQ dominates socioeconomic background for white men

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curves) or IQ (for the gray curves) were set at their mean values.

When people think about the causes of crime, they usually think not only of the role of juvenile delinquent’s age and socioeconomic background but also of what used to be called “broken homes.” It is now an inadequate phrase, because many families do not even begin with a married husband and wife, and many broken homes are reconstituted (in some sense) through remarriage. But whatever the specific way in which a home is not intact, the children of such families are usually more likely to get in trouble with the law than children from intact families.

41

This

was true for the NLSY white males. An intact family consisting of the biological mother and father was associated with better outcomes for their children than any of the other family arrangements. Was the young man ever stopped by the police? Thirty-two percent of white males from intact families compared to 46 percent of all others. Booked for an offense? Fifteen percent compared to 29 percent. Convicted of an offense? Eleven percent compared to 21 percent. Sentenced to a correctional facility? Two percent compared to 7 percent.

Although family setting had an impact on crime, it did not explain away the predictive power of IQ. For example, a young man from a broken family and an average IQ and socioeconomic background had a 4 percent chance of having been interviewed in jail. Switch his IQ to the 2d centile, and the odds rise to 22 percent. (Switch his socioeconomic background to the 2d centile instead, and the odds rise only from 4 to 5 percent.) The same conclusions apply to the measure of self-reported crime.

Scholars have been arguing about the relationship of education to crime and delinquency for many years without settling the issue. The case of the NLSY white males is a classic example. Of those who were ever interviewed in jail, 74 percent had not gotten a high school diploma. None had a college degree. Clearly something about getting seriously involved in crime competes with staying in school. Low IQ is part of that “something” in many cases, but the relationship is so strong that other factors are probably involved—for example, the same youngster who is willing to burglarize a house probably is not the most obedient of pupils; the youngster who commits assaults on the street probably gets in fights on the school grounds; the youngster who is undeterred by the prospect of jail time probably is not much motivated by the prospect of getting a high school degree; and so forth.

Does high school dropout actually cause the subsequent crime? Many people assumed so until Delbert Elliott and Harwin Voss published a study in 1974 that concluded the opposite: Crime diminished after school dropout.

42

Since then, everyone has agreed that eventual dropouts tend to have high levels of criminal activity while they are in school, but disputes remain about whether the rates fall or rise after the dropout occurs.

43

For our purposes, it makes little sense to examine the continuing role of IQ in our usual educational samples when the action is so conspicuously concentrated among those who fall neither in the high school nor the college graduate samples. Running our standard analysis on white males who did not get a high school diploma did not shed much more light on the matter.

44

Given the restriction of range in the sample (the mean IQ of the white male dropout sample was 91, with a standard deviation of only 12.5), not much can be concluded from the fact that the ones at the very bottom of the cognitive ability distribution were less likely to report high levels of criminal activity. For these school dropouts, the likelihood of having been interviewed in jail rose as IQ fell, but the relationship was weaker than for the unrestricted sample of white males.

By now, you will already be anticipating the usual caution: Despite the relationship of low IQ to criminality, the great majority of people with low cognitive ability are law abiding. We will also take this opportunity to reiterate that the increase in crime over the last thirty years (like the increases in illegitimacy and welfare) cannot be attributed to changes in intelligence but rather must be blamed on other factors, which may have put people of low cognitive ability at greater risk than before.

The caveats should not obscure the importance of the relationship of cognitive ability to crime, however. Many people tend to think of criminals as coming from the wrong side of the tracks. They are correct, insofar as that is where people of low cognitive ability disproportionately live. They are also correct insofar as people who live on the right side of the tracks—whether they are rich or just steadily employed working-class people—seldom show up in the nation’s prisons. But the assumption that too glibly follows from these observations is that the economic and social disadvantage is in itself the cause of criminal behavior. That is not what the data say, however. In trying to understand how to deal with the crime problem, much of the attention now given to problems of poverty and unemployment should be shifted to another question altogether: coping with cognitive disadvantage. We will return to this question in the final chapter, when we consider policy changes that might make it easier for everyone to live within the law.

Civility and Citizenship

A free society demands a citizenry that willingly participates in the civic enterprise, in matters as grand as national elections and as commonplace as neighborliness. Lacking this quality—civility, in its core meaning—a society must replace freedom with coercion if it is to maintain order. This chapter examines the contribution of cognitive ability to the capacity for civility and citizenship.

Most manifestations of civility are too fleeting to be measured and studied. One realm of activity that does leave measurable traces is political involvement, which includes both participation in political activities and some knowledge and sophistication about them.

For assessing any relationship between political involvement and IQ, the best data, surprisingly, are from studies of children, and the results are consistent: Brighter children of all socioeconomic classes, including the poorest, learn more rapidly about politics and how government works, and are more likely than duller children to read about, discuss, and participate in political activities. The gap between brighter and duller children in political development widens with age, unlike the static gap across socioeconomic classes.

For adults, the standard theory of political involvement for many years has assumed that socioeconomic status is the vital link. People at higher-status levels vote more, and they know and care more about political matters than do people at lower levels of status. But the available research offers ample evidence that the key element for predicting political involvement is educational level. The people who vote least and who care the least about political issues are not so much the poor as the uneducated, whatever their income or occupation. Why does education matter so much? The fragmentary studies available indicate that education predicts political involvement in America because it is primarily a proxy for cognitive ability.

The NLSY does not have the data for pursuing this manifestation of civility, but it permits us to explore another aspect of it: To what extent is high inteligence

associated with the behaviors associated with “middle-class values”? The answer is that the brighter young people of the NLSY are also the ones whose lives most resemble a sometimes disdained stereotype: They stick with school, are plugging away in the workforce, and are loyal to their spouse. Insofar as intelligence helps lead people to behave in these ways, it is also a force for maintaining a civil society.

A

merica’s political system relies on the civility of its citizens—“civility” not in the contemporary sense of mere politeness but according to an older meaning which a dictionary close at hand defines as “deference or allegiance to the social order befitting a citizen.”

1

The wording of the definition is particularly apt in the American case. Civility is not obedience but rather “allegiance” and “deference”—words with old and honorable meanings that are now largely lost. The object of these sentiments is not the government but a social order. And these things are required not of a subject but of a citizen. Taken together, the elements of civility imply behavior that is both considered and considerate—precisely the kind of behavior that the Founders relied upon to sustain their creation, though they would have been more likely to use the word

virtue

than

civility.

2

The point is that, given such civility, a free society as envisioned by the Founders is possible. “Civil-ized” people do not need to be tightly constrained by laws or closely monitored by the organs of state. Lacking such civility, they do, and society must over time become much less free. That is why civility was relevant to the Founders’ vision of a free society and also why it remains relevant today. In Part IV, we consider further the link between intelligence and the polity. At this point, we ask what the differences are between people that explain whether they are civil. Specifically, what is the role of intelligence?

Much of what could go under the heading of civility is not readily quantified. Mowing the lawn in the summer or keeping the sidewalks shoveled in the winter, maintaining a tolerable level of personal hygiene and grooming, returning a lost wallet, or visiting a sick friend are not entirely dictated by fear of lawsuits or of retaliation from outraged neighbors. They likely have an element of social engagement, of caring about one’s neighbors and community, of what we are calling civility. Most such everyday acts of civility are too fleeting to be caught in the net of observation that social science requires.

Fortunately, the behaviors that go into civility tend to be of a piece, and some acts leave clear traces that can be aggregated and studied. In the preceding chapter, we examined one set of such behaviors, crime. Crime is important in itself, of course, but it also captures the negative pole of disassociation from society at large and the community in particular. Everything we know about the lives of most criminals suggests that in their off-duty hours they are

not

commonly shoveling the sidewalk, visiting sick friends, or returning lost wallets—or doing the myriad other things that signify good neighbors and good citizens. In that light, the chapter on crime may be seen as a discussion of a growing incivility in American life and the contribution that low cognitive ability makes to it.