The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (64 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

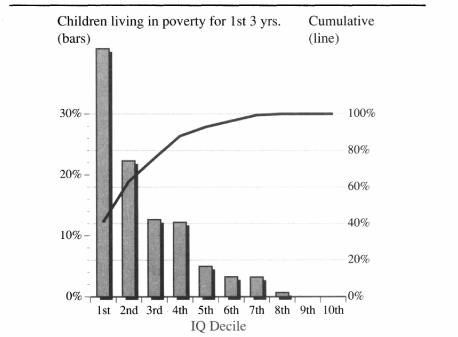

The proportion of children living in poverty is one of the most frequently cited statistics in public policy debates and one of the most powerful appeals to action. In considering what actions might be taken, and what will and won’t work, keep the following figure in mind. It shows the distribution of maternal cognitive ability among children who spent their first three years below the poverty line. Mothers whose children lived in poverty throughout their first three years averaged an IQ of 84. Forty-one percent had mothers in the very bottom decile in cognitive ability. In all, 93 percent were born to women in the bottom half of the IQ distribution. Of all the social problems examined in this chapter, poverty among children is preeminently a problem associated with low IQ—in this case, low IQ among the mothers.

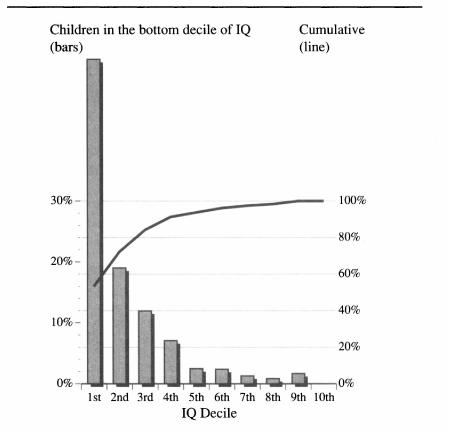

The prevalence of developmental problems among children is skewed toward the lower half of the IQ distribution. Rather than present graphs for each of them, the table below summarizes a consistent situation. See Chapter 10 for a description of the indexes« Low IQ is prevalent among the mothers of children with each of these developmental problems, but none shows as strong a concentration as the developmental indicator we consider the most important for eventual social adjustment: the child’s own IQ. The figure below is limited to the cognitive ability of children ages 6 and older when they took the test.

Sixty-three percent of children who lived in poverty throughout the first three years had mothers in the bottom 20 percent of intelligence

| Prevalence of Low IQ Among Mothers of Children with Developmental Problems | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children in the Worst Decile on: | Percentage of These Children with Mothers in Bottom: | Mean IQ of Mothers | |

| | 20% of IQ | 50% of IQ | |

| Friendliness index, 12-23 mos. | 49 | 82 | 88 |

| Difficulty index, 12-23 mos. | 40 | 71 | 91 |

| Motor and social development index, birth-47 mos. | 38 | 67 | 93 |

| Behavioral problems index, children ages 4-11 yrs. | 42 | 78 | 90 |

Seventy-two percent of children in the bottom decile of IQ had mothers in the bottom 20 percent of intelligence

The mean IQ of mothers of children who scored in the bottom decile of a childhood intelligence test was 81.

5

Overall, 94 percent of these children had mothers with IQs under 100. The extreme concentration of low IQ among the children of low-IQ mothers is no surprise. That it is predictable does not make the future any brighter for these children.

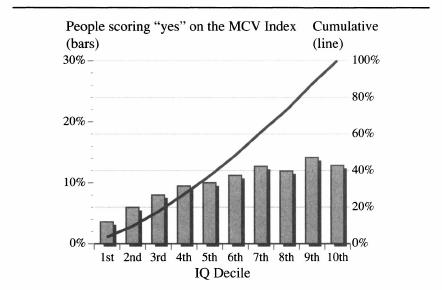

Let us conclude on a brighter note, after so unrelenting a tally of problems. You will recall from Chapter 12 that we developed a Middle Class Values Index. To qualify for a score of “yes,” an NLSY person had to be married to his or her first spouse, in the labor force (if a man), bearing children within wedlock (if a woman), and never have been interviewed in jail How did the NLSY sample break down by IQ? The results are set out in the figure.

Ten percent of people scoring “yes” on the Middle Class Values Index were in the bottom 20 percent of intelligence

The mean IQ of those who scored “yes” was 104« Those in the bottom two deciles contributed only about 10 percent, half of their proportional share. Those in the bottom half of the cognitive distribution contributed 37 percent. As in the case of year-round employment, the skew toward those in the upper half of the cognitive ability distribution is not extreme. This reminds us again more generally that most people in the lower half of the cognitive distribution are employed, out of poverty, not on welfare, married when they have their babies, providing a nurturing environment for their children, and obeying the law.

We must add another reminder, however. There is a natural tendency to review these figures and conclude that we are really looking at the consequences of social and economic disadvantage, not intelligence. But in Part II, we showed that for virtually all of the indicators reviewed in this chapter, controlling for socioeconomic status does not get rid of the independent impact of IQ. On the contrary, controlling for IQ often gets rid of the independent impact of socioeconomic status. We have not tried to present the replications of those analyses for all ethnic groups combined, but they tell the same story.

The lesson of this chapter is that large proportions of the people who exhibit the behaviors and problems that dominate the nation’s social policy agenda have limited cognitive ability. Often they are near the definition for mental retardation (though the NLSY sample screened out people who fit the clinical definition of retarded). When the nation seeks to lower unemployment or lower the crime rate or induce welfare mothers to get jobs, the solutions must be judged by their effectiveness with the people most likely to exhibit the problem: the least intelligent people. And with that, we reach the practical questions of policy that will occupy us for the rest of the book.

Living Together

Our analysis provides few clear and decisive solutions to the major domestic issues of the day. But, at the same time, there is no major domestic issue for which the news we bring is irrelevant.

Do we want to persuade poor single teenagers not to have babies? The knowledge that 95 percent of poor teenage women who have babies are also below average in intelligence should prompt skepticism about strategies that rely on abstract and far-sighted calculations of self-interest. Do we favor job training programs for chronically unemployed men? Any program is going to fail unless it is designed for a target population half of which has IQs below 80. Do we wish to reduce income inequality? If so, we need to understand how the market for cognitive ability drives the process. Do we aspire to a “world class” educational system for America? Before deciding what is wrong with the current system, we had better think hard about how cognitive ability and education are linked. Part IV tries to lay out some of these connections.

Chapter 17 summarizes what we know about direct efforts to increase cognitive ability by altering the social and physical environment in which people develop and live. Such efforts may succeed eventually, but so far the record is spotty.

Chapter 18 reviews the American educational experience of the past few decades. It has been more successful with the average and below-average student than many people think, we conclude, but has neglected the gifted minority who will greatly affect how well America does in the twenty-first century.

In Chapters 19 and 20, the focus shifts to affirmative action policies in education and in the workplace. Our society has dedicated itself to coping with a particular sort of inequality, trying to equalize outcomes for various groups. The country has retreated from older principles of individual equality before the law and has adopted policies that treat people as members of groups. Our contribution (we hope) is to calibrate

the policy choices associated with affirmative action, to make costs and benefits clearer than they usually are.

The final two chapters look to the future. In Chapter 21, we sound a tocsin. Predictions are always chancy, and ours are especially glum, but we think that cognitive stratification may be taking the country down dangerous paths. Chapter 22 follows up with our conception of a liberal and just society, in light of the story that the rest of the book has told. The result is a personal statement of how we believe America can face up to inequality in the 21st century and remain uniquely America.

Raising Cognitive Ability

Raising intelligence significantly, consistently, and affordably would circumvent many of the problems that we have described. Furthermore, the needed environmental improvements—better nutrition, stimulating environments for preschool children, good schools thereafter—seem obvious. But raising intelligence is not easy.

Nutrition may offer one of the more promising approaches. Height and weight have increased markedly with better nutrition. The rising IQs in many countries suggest that better nutrition may be increasing intelligence too. Controlled studies have made some progress in uncovering a link between improved nutrition and elevated cognitive ability as well, but it remains unproved and not well understood.

Formal schooling offers little hope of narrowing cognitive inequality on a large scale in developed countries, because so much of its potential contribution has already been realized with the advent of universal twelve-year systems. Special programs to improve intelligence within the school have had minor and probably temporary effects on intelligence. There is more to be gained from educational research to find new methods of instruction than from more interventions of the type already tried.

Preschool has borne many of the recent hopes for improving intelligence. However, Head Start, the largest program, does not improve cognitive functioning. More intensive, hence more costly, preschool programs may raise intelligence, but both the size and the reality of the improvements are in dispute.

The one intervention that works consistently is adoption at birth from a bad family environment to a good one. The average gains in childhood IQ associated with adoption are in the region of six points—not spectacular but not negligible either.

Taken together, the story of attempts to raise intelligence is one of high hopes, flamboyant claims, and disappointing results. For the foreseeable future, the problems of low cognitive ability are not going to be solved by outside interventions to make children smarter.

C

an people become smarter if they are given the right kind of help? If raising intelligence is possible, then the material in Parts II and III constitutes a clarion call for programs to do so. Social problems are highly concentrated among people at the bottom of the cognitive distribution; those problems become much less prevalent as IQ increases even modestly; and the history of increases in IQ suggests that they occur most readily at the bottom of the distribution. Why not mount a major national effort to produce such increases? It does not appear on its face to be an impossible task. Even the highest estimates of heritability leave 20 to 30 percent of cognitive ability to be shaped by the environment. Some researchers continue to argue that the right proportion is 50 to 60 percent. In either case, eliminating the disadvantages that afflict people in poor surroundings should increase their cognitive functioning.

1