The Bell Tolls for No One (2 page)

Read The Bell Tolls for No One Online

Authors: Charles Bukowski

Bukowski began writing a series of stories about the women he met during the period 1970â1976 which would ultimately take shape as the novel

Women

, and the

Los Angeles Free Press

began serializing them in the February 13â19, 1976, issue with an editor's note calling the sequence a “novel-in-progress” under the title

Love Tale of a Hyena.

(The title was kept for the German edition of the novel:

Das

Liebesleben der Hyaene.

)

17

His relationship with Linda King is portrayed. Liza Williams appears in several; at one of her parties, Bukowski describes meeting Robert Crumb (but declines the invitation to meet the editor of

The Realist

, Paul Krassner). Writing and women form a constant counterpoint in his stories. He plunges into the cauldron of love, passion, sex, attempting to heal the wounds of his past, attempting to find in romantic love a salve for the demons that try him. Yet he can only momentarily find such redemption, and returns to his self, and gains distance from his solitude by crafting the experiences into narrative. His life exists mainly to be transcribed and transformed into words. He goes to Arizona, describing himself writing, and immediately refers to Gertrude Stein and Hemingway, weaving in his encounters with women and children and the life immediately taking place around him at the moment. Sex is a matter of occasional ecstasy and frequent laughter; love is a matter of life and death: He gives us both, in alternation. The stories also exemplify the gender wars of the period, during which women's liberation had begun. Bukowski typically reverses the situation to show how the “politically correct” stance can be easily turned on its head. He also, however, satirizes men, and shows the absurdity of the whole romantic love complex. Pathos, farce, tragedy: Often, humor saves the situation. He is able to defuse the pain by poking gentle fun at the entire absurdity of love relationships. Massage parlors, a pornographer engaging in late-night discussions with his wife, adult bookshops, older women picking up younger men: The entire panoply of the fading sexual revolution is held up to satire and ridicule.

Bukowski's shift to becoming a “professional writer” in 1970 in some ways altered his method of composition. He had always reshaped the same material into poem and story, but now he was devoting his time to writing novels as well as submitting to the adult magazines. Several of the stories included in this volume demonstrate how he worked and reworked this material. He creates the same narrative anew; he doesn't copy, but starts over. He is always telling his autobiography but selecting different details, reinventing instead of rewriting. For example, “An Affair of Very Little Importance” about Mercedes exists in another version in

Women

, but the narrative and emphasis are different. And the story “I Just Write Poetry So I Can Go to Bed with Girls,” for example, also exists as the “Dirty Old Man” installment included here: It keeps some of the plot, but takes a completely different approach to the meeting with Gregory Corso.

18

It is typical of Bukowski's method of selecting episodes from his life and reworking them, adding specific details and usually elaborating on reality by adding invented plot elements. He is constantly engaged in telling and retelling his life, giving it the structure of myth so that the two become inseparable. The basic structure of his life is mythic, a variation on the hero's journey, the genius as hero: his abandoned childhood, primal wounding by his father, and his skin disfiguration, his

wanderings in the wilderness, his near-death by alcoholism in 1954, and his resurrection.

19

These stories from 1948â1985 demonstrate Bukowski's growth as a writer of short fiction. He gradually hones his craft and learns how to combine the tragic and comic modes effortlessly. In his late phase, Bukowski had mastered his style to the point of making the laconic, finely modulated prose we see in “The Bell Tolls for No One.” The mood is swiftly established, and not a word is wasted. His goal in his fiction was to entertain, yet he was driven to explore the dark places, the Nietzschean cave with the monstrous Minotaur. As he once said: “I can't name it. It's just there. The thing is there. I have to go see it. The monster, the god, the rat, the snail. Whatever's out there I have to go see it and look at it and endure it and maybe not endure it but it's needed. That's all. I really can't explain it.”

20

The unspeakable, monstrous, inscrutably violent and tender mystery at the heart of existence will not leave him in peace.

INTRODUCTION NOTES

1

. “The Reason Behind Reason,”

Matrix

, vol. 9, no. 2, Summer 1946 in

Absence of the Hero

, ed. David Stephen Calonne (San Francisco: City Lights, 2010).

2

. Charles Bukowski letter to Whit Burnett, Box 19, Folder 13; Princeton University Library.

3

. François Rabelais,

Gargantua and Pantagruel

, p. 677; “Ultimate Religion,” in

The Essential Santayana

, ed. Martin A. Coleman (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2009), p. 344.

4

.

Absence of the Hero

, pp. 255â270.

5

. See David Stephen Calonne,

Charles Bukowski

(London: Reaktion Books, 2012), pp. 31â32; also see footnote 8, p. 185).

6

. See Erin A. Smith, “Pulp Sensations” in David Glover and Scott McCracken,

The Cambridge Companion to Popular Fiction

(Cambridge University Press, 2012); on Bukowski and

Pulp

, see Calonne,

Charles Bukowski

, pp. 171â173; Paula Rabinowitz,

American Pulp: How Paperbacks Brought Modernism to Main Street

(Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 296â297.

7

. Charles Bukowski, “the lady in red,” in

Dangling in the Tournefortia

(Santa Barbara, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1981), p. 13.

8

. Jack Black,

You Can't Win

, Introduction by William S. Burroughs (Edinburgh: AK Press/Nabat, 2000).

9

. Wallace Fowlie, “Shadow of Doom,” in

The Happy Rock: A Book About Henry Miller

(Berkeley, CA: Bern Porter, 1945), p. 102.

10

. Friedrich Nietzsche,

On the Genealogy of Morals; Ecce Homo

, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), p. 150.

11

.

Kauri

15, July-August 1966, p. 4; on Healey, also see “Eyes Like the Sky” in Bukowski,

Tales of Ordinary Madness

(San Francisco: City Lights, 1983), pp. 175â180.

12

. Hillary Chute, “Graphic Narrative,” in Joe Bray, Alison Gibbons, and Brian McHale, eds.,

The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature

(London and New York: Routledge, 2012), p. 410. Also see Patrick Rosenkranz,

Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution, 1963â1975

(Seattle: Fantagraphic Books, 2002).

13

. For reproductions of Wilson's illustrations of Bukowski stories, see Patrick Rosenkranz,

Demons and Angels: The Mythology of S. Clay Wilson, Volume 2

(Seattle: Fantagraphic Books, 2015).

14

. Crumb remarked about Bukowski: “I like his ironic humor and his alienated attitude about the world in general. He expresses that in very succinct and eloquent terms.” See D.K. Holm, ed.,

R. Crumb, Conversations

(Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2004), p. 208.

15

. On

The Way the Dead Love

, see Abel Debritto,

Charles Bukowski, King of the Underground: From Obscurity to Literary Icon

(New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), pp. 127, 135â6.

16

. The poem may be found in

Pacific Northwestern Spiritual Poetry

, ed. Charles Potts (Walla Walla: Tsunami Inc., 1998), pp. 48â51.

17

.

Los Angeles Free Press

, Feb 13â19, 1976, p. 20.

18

. See

Absence of the Hero

, pp. 99â111.

19

. David Stephen Calonne, “Bukowski and the Romantic Conception of Genius,”

Jahrbuch der Charles-Bukowski-Gesellschaft 2011/12/13

, pp. 217â218.

20

.

The Charles Bukowski Tapes

, DVD, directed by Barbet Schroeder (Detroit, MI: Barrel Entertainment, 2006).

A Kind, Understanding Face

T

he parents died younger than it is usual to die, the father first, the mother soon afterward. He didn't attend the father's funeral but he was at the last one. Some of the neighbors remembered him as a boy and had thought him a “nice child.” Others only remembered him grown, on sporadic one or two week stays at the house. He was always in some far off city, Miami, New York, Atlanta, and the mother said he was a journalist and when the war came without his becoming a soldier, she explained a heart condition. The mother died in 1947 and he, Ralph, entered the house and became a part of the neighborhood.

He became the victim of scrutiny, for the neighborhood was decently average, home-owned, home-lived rather than rented so that one was more aware of the permanence of things. Ralph seemed older than he should have been, so quite worn. At times, though, in favorable shades of light he was almost beautiful, and the left lower eyelid would sometimes twitch behind an almost gaudily lit eye. He spoke little and when he did he seemed to be joking, and then he would walk off, either too fast briskly, or he would slouch-swagger off, hands in pockets and flat-footed. Mrs. Meers said he had a “kind, understanding face.” Others thought he sneered.

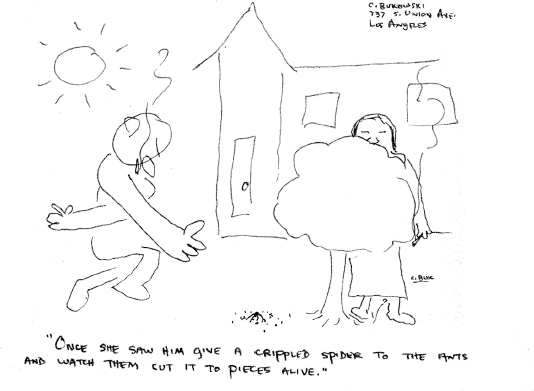

The house had been well cared forâthe shrubbery, the lawns and the interior. The car disappeared, and soon in the backyard were three kittens and two puppies. Mrs. Meers, who lived next door, noticed that Ralph spent much time in the garage breaking the spider webs with a broom. Once she saw him give a crippled spider to the ants and watch them cut it to pieces alive. This, beyond one incident, gave vent to the most early conversations. The other: coming down the hill he had met Mrs. Langley and had said, “Until people learn to excrete and copulate in public they will be neither decently savage nor comfortably modern.” Ralph had been intoxicated and it was understood that he was grieving. Also, he seemed to give more time to the kittens than the puppies, almost teasingly so, and this, of course, was strange.

He continued to grieve. The lawns and shrubs began to yellow. He had visitors, they kept late hours and were sometimes seen in the mornings. There were women, stout, heavy-laughing women; women too thin, shabby women, old women, women with English accents, women whose every other word referred to the bathroom or the bed. Soon there were people day and night. Sometimes Ralph was not to be seen for days. Somebody put a duck in the backyard. Mrs. Meers took to feeding the pets and one evening Mr. Meers, in an anger, attached his hose to Ralph's faucets and gave the place a good soaking down. He wasn't stopped, wasn't even noticed, except by “a thin, terrible-looking man” who came out of the screen door with a cigar in his mouth, walked past Mr. Meers, opened the incinerator, looked into it, closed it, walked past Mr. Meers and back into the house.

Sometimes at night the men fought in the backyard and once Mrs. Roberts (on the other side) called the police, but by the time they arrived everybody was in the house again. The police went into the house and remained some time. When they made their exit they were alone.

It began to be almost too much when suddenly the neighbors noticed that the people were gone. The duck was gone too. It began to be quiet nights. In the days there was only one woman, thin-faced, with an English accent and rather snobbish, though cleanly dressed and younger than the others had been. Ralph was seen coming home with library books and then leaving every morning at 7:15 A.M. in overalls. He began to look better, though Mrs. Meers smelled whiskey on the woman the few times she spoke to her. Ralph began to water and trim the yard. The left lower eyelid was improved. He spoke more. “People are good. Everybody's good. I hope we can be good friends,” he spoke to Mrs. Roberts. “I guess I've been a kid most of my life. I guess I'm just growing up. And don't mind Lila. She's . . . she's really . . . ” He didn't finish. He just smiled and waved a hand and turned the hose onto a bush.

Sometimes on weekends they saw him intoxicated, and her, of course; but he always made work and was very kind, really a good-natured person. “If she could only be like Ralph. Oh, I know he takes a drink! But he's a brilliant boyâand that job, you know! He is so nice. But I guess he needs her.”

He must have needed them too. They started coming back, first a few, and then the rest. The woman, Lila, seemed to dislike it most. She was in a fury but Ralph just laughed. Then the duck came. When the duck came Lila went into silence. The kittens and puppies were almost full-grown and the poor duck, once master, had its troubles. The “thin, terrible-looking man who went to the incinerator” was seen building a pen and thereafter the penned duck was understood by the neighbors to belong to the “thin, terrible-looking man who went to the incinerator.”

One of the dogs died. They bought a piano and played it almost continually, day and night, for a week then left it alone. They buried the dog behind the garage, setting up a cross in the neck of a whiskey bottle half sunken in the soil. But they had buried the hound shallow and it set up an odor. One night a husky woman invaded the grave and burned the remains in the incinerator, cussing loudly and violently, laughing and then vomiting and crying. “It's not death that aches us, it's the getting older, older . . . wrinkled hands, wrinkled face . . . Christ, even my keester's wrinkled! Christ, Christ, old age: I hate it, hate it!”

They evidently sold the refrigerator. Everybody tried to help the moving van men get it into the truck. There was much laughing. The piano went too. It was understood that Lila had tried a suicide and failed. For several days she was very drunk, dressed in an extremely short skirt and four inch spiked heels. She spoke to everybody, even the neighbors.

Some of the crowd thinned out. It was understood that Ralph was charging rent. He was getting thinner and quieter. He bought some seed and planted a lawn, fencing off the new soil with stakes and string. He was seen leaving early every morning in his suit, and several weeks later he was leaving at 7:15 A.M. in his overalls. The crowd remained, though, but weren't quite as noisy. In a fashion, the neighborhood had accepted the house. The lawn came up fine, and it wasn't unusual to see Ralph, in the evenings, speaking to Mr. Meers as they worked about the yards. The other inhabitants seemed to have a certain disdain and central fancy in mind, but Ralph was nice, even on the weekends when he did take a drink. He was just too easy-going putting up with those people; and you could see, he did care much for Lila.

The piano came back. The refrigerator came back. Lila began to wash Ralph's clothing, though Mrs. Meers still smelled whiskey when she spoke to her. Lila had something though. She was really an upper class girl meant for Ralph. She wasn't, in spite of it all, as Mrs. Roberts said, quite like those others. They both had education and good upbringing. You could see that. Ralph had been a journalist . . .

So Ralph's suicide was a real surprise. Of course, they all are, though they say it's old stuff, nothing new. The note seemed written in a moment of agonized frenzy. And on the back of the note were some disconnected notations taken from his readings, as strange as everything else had been:

I saw some manticores, a most strange sort of creatures, which have the body of a lion, red hair, a face and ears like a man's, three rows of teeth which close together, as if you joined your hands with your fingers between each other: they have a sting in their tails like a scorpion's and a very melodious voice.âRabelais.

The absolute love of anything involved the love of universal good; and the love of universal good involves the love of every creature.âSantayana.

Warcollier established himself before World War I through an invention for the manufacture of artificial jewelry from the scales of a fish. Factories were opened in France and the United States . . .

The lawn went to pot.