The Book of Animal Ignorance (23 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

T

he histories of humans and house mice (

Mus musculus

) are inseparable. The original

Mus

had lived happily outdoors in northern India for millions of years but as soon as our hunter-gatherer ancestors started to farm in Mesopotamia 10,000 years ago, the mouse lifestyle was also transformed. Permanent houses and grain stores inadvertently provided reliable food and shelter and the small, swift, resourceful mouse needed no further encouragement. The very name âmouse' (from Latin

mus

and Greek

mys

) ultimately derives from the Sanskrit root

mush

, which means mouse and also to steal. Hence wherever we went thereafter â on foot, in carts, or by ship â the little thief kept us company.

As a result, house mice can be found wherever there are settled populations of people (as well as many places where there are none). They live on all the continents; at altitudes as high as 15,600 feet; as far north as the Bering Sea; and as far south as the sub-Antarctic islands. They live in coal-mines, meat freezers, underground railway tunnels. This is partly because they can live on almost anything â seeds, roots, insects, larvae, food scraps â and if they need to drink at all, licking dew or condensation is enough. But the real source of their success is that they can rapidly adapt their behaviour to suit the environment they find themselves in. Most animals change slowly. Wherever we take them, mice not only survive: they find a way to thrive.

Their prodigious fertility helps. Mice are sexually mature at four weeks; a single pair of mice can produce 500 offspring in a year. It's a competitive business and female mice are extremely promiscuous. The bigger the penis, the longer and more frequent the copulation; and the higher the volume of ejaculate, the more likely conception is to occur. A quarter of all litters are the product of more than one father, a strategy that not only ensures genetic diversity but also helps to prevent any new male

partner eating a female's offspring, just in case they are his. In extreme cases, she will even reabsorb the foetuses to prevent them being eaten.

Mouse sex is not without its romantic side. Male mice sing complex songs in ultrasound, both to attract mates and during the act itself. Slowed down, they sound disconcertingly like Clangers. Most murine communication is via urine, which they dab around continually. Age, sex, health and sexual status are all encoded in a mouse's urine âsignature'. Male scent is used territorially; female scent is to do with breeding, a kind of mousy âgirl talk'. It's one of the reasons mice dislike peppermint â it scrambles their communication network.

Sanskrit has forty words for

âmouse'.

Mushka

is âlittle

mouse' but also means

âtesticle'. From this, we get

âmusk' (from the scrotum-like

gland of the musk deer)

and âmuscle' (from its

mouse/testicle-

like

movement under the skin)

.

What do we get out of the relationship? House mice now comprise 98 per cent of all animals used in genetics research. Amazingly, most of these derive from just two breeding strains (C57BL/6 and L/10) sold to a laboratory in 1921 by Massachusetts schoolteacher and âfancy mouse' breeder, Abbie Lathrop. Also, mice are what most carnivorous predators eat most of the time. This is a very good thing: if there weren't any mice, they would be forced to eat our livestock. Indeed, without the little thief, it is unlikely that the ancient Egyptians would have bothered domesticating cats in the first place.

A

strong contender for the planet's ugliest animal, the Naked mole rat looks like a flaccid penis with teeth. It is also one of the least well named, being neither naked, a mole, nor a rat. Cousin to the porcupine and the guinea pig, it is a 3-inch long rodent, which uses its huge incisors to carve out tunnels in the hard desert soil. Although it looks completely bald, it does have whiskers on its face and tail which act as navigational sensors, and hairy toes which sweep soil behind it like a broom.

Naked mole rats feel

no pain. They lack a

neurotransmitter

chemical called

âSubstance P', which

may be an adaptation

helping them cope

with the near

poisonous levels of

carbon dioxide in their

stuffy burrows

.

They are the only mammals to live in organised colonies, like termites and bees. Only one female breeds, serviced by a harem of three males and supported by as many as 300 âworkers' and âsoldiers', who divide the tunnelling, childcare, food collection and defence functions between them. This behaviour is called

eusocial

(

eu

-meaning âgood') and has evolved in response to the harsh conditions of their home territory in eastern Africa, where a lack of rain and food mean they need to cooperate to survive. A large colony gives them better odds of coming across the sparse underground vegetable tubers which cater for all their food and drink needs. By carefully boring into them, they can keep the tubers growing, providing a sustainable food source for years.

Naked mole rats (

Heterocephalus

glaber

, the âodd-headed smooth one') spend almost all their life underground. Their eyes have become so useless that they usually keep them closed. They can also close their lips behind their teeth, to keep their mouths free of soil while digging.

NAKED CHAIN GANG

Except for the queen and her harem, digging is what mole rats do. A quarter of their muscle is in the jaw, and a third of their brain is used to process information from their mouths. Colonies contain miles of tunnels; an individual worker can dig half a mile a month when the soil is softened by rain. That's equivalent to a human digging the 12 miles from central London to Heathrow Airport. Mole rats are practically cold-blooded: when they're not digging or eating, they sleep heaped together in communal chambers to keep warm.

As with other mammals, the newborns are suckled by the mother. The queen gives birth to between twenty and thirty âpups' at a time, but only has twelve nipples â a unique mismatch for a mammal. Pups get their food by waiting patiently and taking turns.

Queen mole rats are fat bullies, nose-shoving the underlings when their work isn't up to snuff. A combination of work stress and intimidation seems to be enough to suppress the sex hormones in both male and female workers, although the queen supplements this with a special chemical in her urine, the equivalent of bromide in a soldier's tea. A âsterile' worker that is removed from a colony becomes sexually active within a week.

A queen and her harem can live for twenty-five years, producing over a thousand offspring. When she dies, vicious fights break out between the largest remaining females to decide the next âqueen'. Mole rat colonies are like large, in-bred, dysfunctional families. The lack of interbreeding with other colonies means that the workers are propagating some of their own genes by helping to raise a conveyor belt of siblings.

T

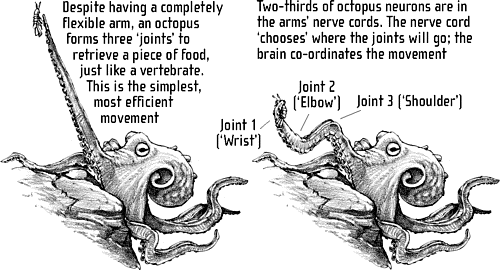

o look at, octopuses are about as different from humans as it's possible to imagine: no body to speak of, just a head sprouting eight arms (it's very biologically incorrect to call them legs or tentacles). So it's pleasing to discover that they have larger brains, relative to body weight, than any animals except birds and mammals, and that they get bored easily. If they are kept in environments enriched with natural features, they grow faster, learn faster and remember more of what they learn than if they are kept in bare tanks. They remember places where they might find food, and where they have already hunted. And although octopuses are mostly solitary, there is evidence that they can communicate and, if kept together, they establish hierarchies and avoid confrontations. For all these reasons, in the UK octopuses enjoy the same legal status in labs as vertebrates.

Octopuses are

good mimics. Some

imitate other

dangerous animals

like sea snakes

and lionfish.

Others pretend to

be drifting clumps

of algae or waterlogged

coconuts

.

What they are not so good at is recognising the sex of other octopuses (or octopodes, but never octopi: the word is derived from Greek, not Latin). Put two octopuses in a tank and they will start to copulate regardless of sex. Thirty seconds into a male-on-male encounter there's usually an unembarrassed disentangling, although some of these gay clinches can last for days. In one case, the two males weren't even from the same species. Despite Japanese artists' persistent obsession with giant octopuses pleasuring women in eight erogenous zones simultaneously, octopus sex is a polite affair, carried out at arm's length. One of the male's eight arms is for mating and it differs from the others by having a groove on its underside and a grasping tip called a ligula which in some species inflates with

blood, rather like a mammal's penis. The arm carefully places a packet of sperm in a corresponding slot in the female's mantle (the body/head). The ligula then breaks off and remains embedded in the female. The male dies within a few months of mating. Although octopuses can regenerate lost limbs, they can't grow a new sex arm.

THE

OCTOPUS

ELBOW

The male blanket octopus takes sexual discretion to a new level. He is 40,000 times smaller than the female and his technique involves tearing off his mating arm, placing it somewhere on her body and then swimming off to die. Given that this is roughly equivalent to a herring nudging a blue whale, it's unlikely that she's even aware of him. Meanwhile his disengaged arm crawls into her gill slit, where it can live for as long as a month, until her eggs are mature. She then retrieves it, tears it open like a packet of café sugar and sprinkles the sperm over her eggs.

Octopuses are as dextrous as they are smart. They can open jam-jars, use stones as tools to open shells and wield snapped-off jellyfish tentacles as weapons. Some âwalk' on two arms, as if they were bipeds. They use their body muscles to squirt themselves forwards, reaching speeds of 25 mph. They can even âfly' using this method â squirting themselves right out of the water to escape predators. As octopuses have no skeleton â the only hard part of an octopus is its parrot-like beak â they can squeeze through spaces as small as their eyeballs.