The Book of Animal Ignorance (24 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

T

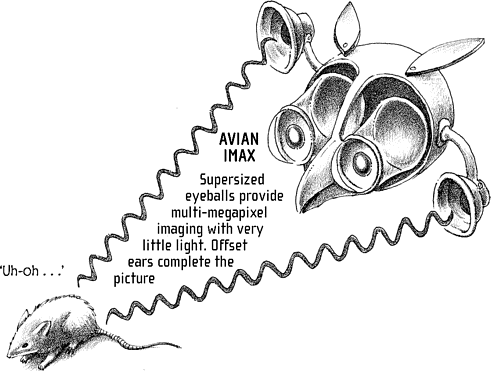

he large, slow-blinking eyes lend the owl's face an expressive quality most birds lack and this has doubtless contributed to its reputation for wisdom. In fact, an owl is not overburdened with brain. Its eyeballs are almost as large as a human's, even though its skull (without feathers) is barely the size of a golfball. This doesn't leave a lot of room for problem-solving. Owls look as they do because they are supremely well adapted for the job of catching small prey at night. Their huge pupils capture a lot of light and the eyeball is shaped like a café salt-shaker rather than a sphere to allow space for the largest possible retina. The retina itself has many more light-sensitive rods than detail-focusing cones, enabling owls to see when the light level falls to almost nothing. A long-eared owl's (

Asio otus

) eyes are so sensitive that it can locate a stationary mouse in light levels equivalent to a football stadium illuminated by a single candle. The downside of such big forward-facing eyes is that owls can't move them. If they want to change their range of view, they have to swivel their head. If they want to judge an object's position accurately, they bob their heads round, reading it from slightly different angles.

AVIAN

IMAX

But eyes are only half the story. An owl's ears are, in contrast, very sensitive. The flat feather-dishes on its face help to capture

sound waves like a pair of satellite bowls, channelling them to its ears, which are huge vertical slits running down both sides of the skull. Sometimes these are cock-eyed (or, rather, cock-eared) on the head, with one higher than the other, or else the owl can manipulate its ear-flaps to create different-sized openings. This allows it to calculate the precise location of its prey by estimating the tiny span of time it takes for the rustling sound of a mouse to get to each of its ears. It is accurate enough for some species to hunt in total darkness.

As well as unusual sight and hearing, owls have evolved a unique system for silent flight. Their bodies and legs are covered with a great number of downy feathers, and even their flight feathers have unzipped, fringed ends to soften the flow of air over them. This makes them look a lot larger than they really are. The long-eared owl has a 3-foot wingspan but weighs less than an orange. To hide, it sucks in its feathers and manages a reasonable impression of a branch.

In India it is common to

call a foolish person âan

owl' â owls are

considered bad omens,

messengers of ill luck, or

servants of the dead

.

For a long time owls were grouped with falcons, but they now have their own order,

Strigiformes

, from

strix

, the Greek for âowl' and the root of the word âstrident'. The name mimics the owl's sound, as does âowl' itself â which comes from the Latin

ululatio

, âa cry of lamentation'. The owl's cry and nocturnal habits associate it with omens of death and ill-fortune in almost every culture.

T

he relatively recent advances in molecular analysis which allow us to trace the family tree encoded in an animal's genes have thrown up numerous surprises, and nowhere more so than with the pangolin or âscaly anteater', a strangely beguiling mammal that looks like a pine cone with legs. For a long time it was classified with the anteaters and armadillos, because it looks and acts like them. Yet its genes tell a different story: it is actually a carnivore, brother under its scales to cats, dogs and bears.

There are seven pangolin species, four in Africa, three in Asia, in their own order, the

Pholidota

, or âhorny-skinned ones'. All but two have prehensile (grasping) tails that enable them to climb trees. They are mostly nocturnal, emerging from their burrows at night to feed on ants and termites. Like the aardvark â to which they are not related â they operate mainly by smell, tearing open the nests with powerful claws and âdrinking' the residents in large gulps. The Giant pangolin (

Manis gigantea

) of Africa can extend its tongue 16 inches. When not in use it is rolled up in a sheath deep in the chest cavity, its powerful muscles anchored at the pelvis. The tongue is covered with incredibly sticky mucus, supplied by a large gland in the chest. They have no teeth but instead grind their food in their stomachs, swallowing small stones and sand, just as birds fill their gizzards.

In China pangolin are

known as âhill carp' and

their flesh is a delicacy

fetching more than £20

a pound. The animals

are killed to order in

restaurants, the warm

blood drunk as a tonic

.

Pangolins have a curious walk, slowly ambling on all fours by resting their front knuckles on the ground and curving the claws underneath. When they want to speed up they walk on their hind legs, rolling forwards, balanced by their tail. A hungry pangolin can wipe out an

insect colony in thirty minutes. They are highly intelligent predators; if a termite nest proves too big to finish off in one go, they will seal it up and return the following day.

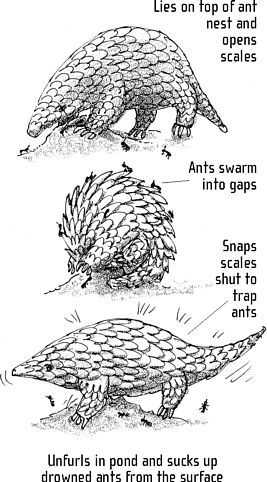

ANT TRAP

âPangolin' comes from the Malay

peng-goling

, meaning âsomething that rolls up'. All species can roll into a ball to defend themselves. Even a mother carrying her baby on her tail will, when faced with danger, simply roll the young one up inside her. They can erect their overlapping scales, made from keratin (like human hair and nails) and shut them like powerful scissors, chopping off anything that pokes between them, including fingers. The scales are, inevitably, a challenge when mating. Pangolins lie side by side, entwining their tails and forelimbs, so the male can slide in to one side of the tail. As for giving birth, happily the scales don't harden until several days later

There is something mysterious about pangolins, beyond their surprising genetic provenance. Among the Lele people of northern Democratic Republic of the Congo, they are the inspiration for a fertility cult: scaly like a fish but able to climb trees; shaped like a lizard but suckling their young; and giving birth, like humans (usually) but few other animals, to just one offspring at a time. Ironically, it is this very strangeness that most threatens their survival, since across Africa and Asia they are eaten as ritual food, and their scales and body parts are used for adornment and traditional medicine.

P

arrots are probably the best-known birds in the world. After cats, dogs and rabbits, budgerigars (which are a kind of parrot) are the world's most popular pets. Almost all parrots are brightly coloured and they have names to match: Rainbow lorikeet, Purple-crowned lorikeet, Red-rumped parrot, Blue-crowned hanging-parrot, Sulphur-crested cockatoo, Peach-faced lovebird, Blue-and-yellow macaw. The colours in their feathers result from completely different molecules from those of any other colours in nature. Most parrots are green and males and females are almost identical in colour, but whereas male Eclectus parrots are bright green with scarlet underwings, the females are bright red with violet-blue breasts. For many years they were thought to be different species. Eclectus parrots are also the only species where the female is more colourful than the male.

Parrots are an ancient

group, which split off

from the other bird

families very early on.

The oldest parrot fossil

is 55 million years old,

found in Walton-

on-

th

e-

Naze in Essex, England

.

Other unique parrots include two New Zealand varieties: the Kea (

Nestor notabilis

), or Mountain parrot, which is large and strong enough to mount the back of a sheep and tear out the fat round its kidneys while it's still alive, and the nocturnal Kakapo (

Strigops habroptilus

, or âsensitive-eyed owl') the world's heaviest parrot and the only one that cannot fly. The world's smallest parrot, the Buff-faced pygmy parrot (

Micropsitta pusio

), is just over 3 inches long and the largest, the Hyacinth macaw (

Anodo-rhynchus

hyacinthinus

), stands more than 3 feet tall. Most birds can move only one half of their beaks but parrots can move both. Their beaks are incredibly strong and close with a force of 350 lb per square inch but they have just 400 taste buds. This is a tiny number compared to people (who have 10,000) or cows,

which, for some unknown reason, have about 25,000, but it's a lot for a bird. Parrots are among the very few birds that show any interest in sweet things. (Hummingbirds also like sweetness, but have only a tenth as many taste buds â between forty and sixty).

Parrots make loud, discordant shrieks, squawks and screams: very few have anything that could reasonably be described as a âsong', but the ancient Romans discovered they could speak and taught them to say âHail Caesar'. At first, talking parrots (imported from India) cost more than human slaves but eventually they became so common that the Romans got bored with listening to them and took to eating them instead.

THE LOVE BOOM

No one knows how parrots get their remarkable ability to talk. No parrot in the wild has ever been observed to mimic the call of another bird or animal. In captivity, however, they readily copy any commonly heard sound (such as doors slamming or car horns) as well as speech. Women and children are better at teaching them to talk than men, and African Greys, the least colourful of parrots, are the best pupils, able to mimic human speech perfectly. With the help of Dr Irene Pepperberg, Alex, an African Grey (

Psittacus erithacus

) bought in a Chicago pet shop in 1977, now speaks 200 words and fifty sentences. African Greys go on adding vocabulary throughout their lives and can live to be eighty years old. In 1800, the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt encountered an elderly Amazon parrot in South America that could speak forty words of Ature, a language whose human speakers had long since died out.