The Book of Animal Ignorance (25 page)

Read The Book of Animal Ignorance Online

Authors: Ted Dewan

Y

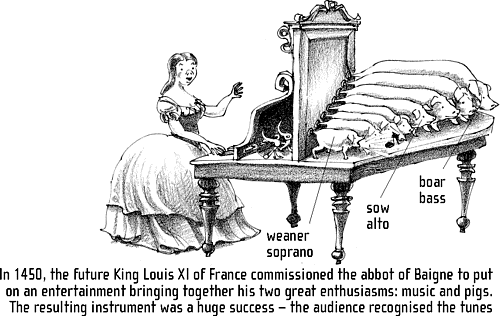

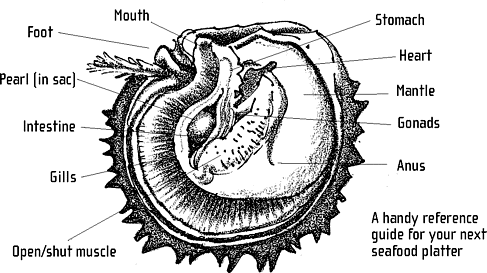

ou are very unlikely to find a pearl in your plate of restaurant oysters. Despite the confusing use of the name, edible oysters are about as closely related to pearl oysters as humans are to marmosets. Both are bivalves, anchoring themselves to rock in shallow seas and filtering algae from the current, but they are from entirely different orders and only one produces pearls of commercial size and value. Pearl oysters, close cousins to the scallop, live in tropical seas and can grow to the size of a dinner plate.

Another widespread misconception is that pearls are formed when a grain of sand or grit becomes trapped inside the oyster's shell. If that were true, pearls would be commonplace rather than highly valued rarities. The oysters' world is full of grit; they inhabit a universe of sand, and they spend their lives constantly ingesting and expelling it, with no trouble. Pearls are triggered by more serious intruders. These might be small bits of debris â pieces of bone, shell or coral, for instance â but in most cases it is something more purposeful. Oysters are troubled by various parasites, including species of worms, sponges and mussels, which drill through the mollusc's shell. This is the kind of major irritation which triggers pearl formation.

Jeweller Pierre Cartier

acquired his Fifth

Avenue flagship store

in 1917 for $100 plus a

natural pearl necklace

valued at $1 million

($15 million in today's

money)

.

Having been invaded, the oyster acts to isolate the parasite inside a âpearll sac'. The whole of the inside of its shell is covered by an organ called the mantle, which secretes mother-of-pearl. Also known as nacre, this is a wonder substance, strong yet flexible and lustrous, made by sandwiching calcium carbonate crystals between layers of an organic secretion similar to keratin. It entombs the enemy alien in successive coatings and the end result is a pearl. Pearl

oysters can manage up to four layers per day but to create a layer of nacre a twentieth of an inch deep takes two years; a finished pearl, fifteen to twenty. That's why a ton of oysters might yield as few as three pearls, and the chances of them being perfectly spherical are, literally, one in a million. A single oyster might get several goes; in the wild they can live for eighty years.

MORE LIKE US THAN MOST PEOPLE THINK

The rarity and beauty of pearls led to many theories about their origin: that they were the result of dewdrops falling into the oyster while it sunned itself at dawn; or they were gallstones or crystallised angels' tears; or came from bolts of lightning. The âgrain of sand' idea was first posited in seventeenth-century Italy, while in the nineteenth century marine scientists proposed dead oyster eggs. It wasn't until the first decade of the twentieth century that French and Japanese researchers identified the pearl sac theory, leading to the first artificially cultured pearls.

Most modern pearls are farmed; it is a big global business with an annual turnover of over £300 million. It is a slow process. Each animal is opened and has a bead of mussel shell and a piece of mantle (cut from a âdonor' oyster) carefully inserted into its gonad. As the mantle fuses with the surrounding tissue, it is stimulated into producing a pearl sac, coating the bead with nacre. Two years later you get something that is indistinguishable from a natural pearl â just don't scratch it too hard.

T

wo-thirds of all the birds in Antarctica are penguins. The largest is the Emperor penguin (

Aptenodytes forsteri

, meaning âwingless diver'), which can grow to a height of 3' 11", dive 1,700 feet deep and hold its breath for fifteen minutes. Forty million years ago there was a much larger Antarctic species,

Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi

, which was 5' 7" tall â the same height as Eddie Izzard or Michelle Pfeiffer. Emperor penguins are famous for their dogged dedication as parents. They take it in turns to look after their egg in bitter subzero weather, making epic trips to find food and losing 40 per cent of their body-weight in the process. Despite this, only 19 per cent of Emperor penguin chicks survive their first year. This must put a strain on the relationship.

It's often said that Emperor penguins mate for life, but in fact nothing could be further from the truth. While faithful for the breeding season and when the chick is being reared, at other times Emperor penguins have much lower rates of fidelity than smaller species. At least 85 per cent of Emperor penguins cheat on their partners. They're mostly straight, though, unlike Roy and Silo, two Chinstrap penguins at New York's Central Park Zoo, who hit the news when they built a nest together, rejected any advances from females and raised an egg. Silo eventually left Roy to pair up with a female named

Scrappy and may well be the first documented case of an ex-gay or bisexual penguin.

Penguins have much

denser feathers than most

birds, more than seventy

per square inch, to keep

them waterproof. Their

black-

and-

white colouring

is designed (like fish) to

blend in with the sea

when looked at from

either above or below

.

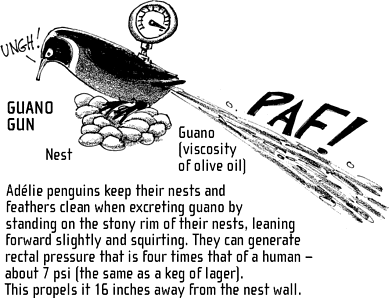

By no means all penguins live on icebergs. Fiordland crested penguins from New Zealand nest in coastal rain forests; Galapagos penguins in tropical volcanic caves; Fairy penguins in burrows; and the Humboldt penguins of Chile in guano, piles of ancient bird droppings. Many penguins spend 75 per cent of their lives at sea. Only Emperor and Adélie penguins live exclusively in the Antarctic. Adélie penguins (

Pygoscelis adeliae

) are named after a French explorer, Jules Sébastien César Dumont D'Urville (1790â1842). In 1840, his ship reached an island off the Antarctic ice shelf, which his men named D'Urville Island in his honour. Later, they came across a little, fat penguin with a black coat and a white apron and named it after his wife, Adélie. The Adélie penguin lives in vast communities of up to 750,000 birds. Like other penguins, they have a manoeuvre called a âslender walk', in which they pin their flippers back when squeezing through crowds. Female Adélie penguins build their nests with stones, a rare commodity in Antarctica and one for which they are willing to pay. When their partner's back is turned, they trade âintimate favours' with other single males in return for bigger, better stones â the only known example of bird prostitution. âClient' males are sometimes so satisfied with the service that females can come back for more stones without offering sex, merely a little light courtship. One particularly flirtatious female managed to acquire sixty-two rocks in this way. The males clearly believe the loss of stones is worth it for the opportunity to father more chicks. Zoologists speculate that the female may be trying to improve the genetic variability of her offspring.

Or she could just be having fun.

T

here are about a billion pigs in the world and more than half of them live in China. The Chinese relationship with the pig is a long one: it was one of the places where the wild boar (

Sus scrofa

) was first domesticated, over 9,000 years ago, and to the Chinese âmeat' still means âpork'. Pork is now the world's most popular meat: 85 billion tons are consumed annually, a third more than beef or chicken. Traditionally, its popularity has been related to the thick protective coating of fat that made it ideal for curing (the process of salting, drying or smoking which preserves the meat by preventing the fat from oxidising). In the last decade, health concerns have led to a halving of the fat content, the extra weight mostly being replaced by water. As well as food, dead pigs are a rich source of medical products such as insulin, their skin makes high-quality leather and their bristles are used in paintbrushes.

Throughout this long history of usefulness, humans have had an ambiguous relationship with the pig. To be a âpig' implies gluttony, stubbornness and a lack of attention to personal hygiene. At the same time, we admire them for their intelligence and pluck. They are gregarious, playful animals and, as a result, are harder to herd than sheep or cattle: if a pig can escape, it will. Pigs eat both plants and meat, which makes them invaluable as recyclers of human food waste. But pigs don't eat âlike pigs'. They have a third more taste buds than we do (they don't like lemon rind or raw onions) and unlike sheep, horses (or humans) rarely overeat.

Pig stem cells are being

used to research human

diseases. In order to track

them once injected,

Chinese geneticists have

crossed a pig with a

jellyfish to produce

piglets whose tongues and

trotters glow fluorescent

green in ultraviolet light

.

However, their âdustbin' status, which made them the backyard animal of choice for Asian and European peasants, also cemented their reputation as an âunclean' animal, forbidden for Jews, Muslims and Seventh Day Adventists.

In terms of cleanliness, pigs are actually very particular. They are the only farm animals that make a separate sleeping den (which they keep spotless) and use a latrine area. They just don't look clean. They turn the ground more efficiently than any plough, ârooting' incessantly with their snouts. This, combined with rain, quickly leads to mud. But pigs don't âsweat like pigs'. Because they have no sweat glands, suffer from sunburn and carry a thick insulating layer of fat, they need a mud wallow to keep them cool and protected.

Pigs are highly intelligent. Like dogs they can be easily housebroken, taught to fetch, and come to heel. Pigs can learn to dance, race, pull carts and sniff out land-mines. They can even be taught to play video games, pushing the joystick with their snouts, something that even chimps struggle to master. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries âlearned pigs', dressed in natty waistcoats, amazed audiences with tricks. Pigs have even put on trial and hanged for murder. Maybe it's this intelligence that some people find unsettling. When a pig fixes you with its long-lashed, forward-facing eyes, and sniffs you with its snout (which is 2,000 times more sensitive than a human nose), a connection is made that goes well beyond the food chain.

THE PIG ORGAN