The Book of Duels (22 page)

Authors: Michael Garriga

Arthur John (Jack) Johnson, 35,

World Heavyweight Boxing Champion & Fugitive from “American Justice”

P

op put his belt to my back regular as the mindless and violent Galveston weather that spun his birds about in the sun and in the rain, and he would come again, a hurricane of a man, to hit me in the head with a skillet so’s I couldn’t run a comb through my hair for a week, or he’d swing his jump rope that whipped the wind just as it cracked against my skin, random as The Numbers, till that summer morn when I brought Mama’s red clay pitcher filled with water to the rooftop and there I set it on the stoop and removed one by one his trained pigeons from their coop and dunked them, beak-down, till their wings quit batting my forearms and their last living breath bubbled up and popped into thin air and was gone forever and then I set them out on a sideboard like in these pheasant still-life paintings hung against the velvet walls in this well-appointed room, just so I’d know the exact minute of my next beating—and it was my last one, too—as soon as I could stand again I left home and fought my way through the world and beat black men in makeshift rings or barbershops, but the first time I fought a white man, the cops threw us both in the clink with nothing to do but spar, two pugilists training for ninety straight no-women days, and he taught me to give it as well as to take and when I got out I swore I’d never spend another dime of my time in a place like that and I got out and put the whipping on blacks and whites alike, though truthfully, they were all just Pop to me.Rasputin takes my queen so I, according to the rules we’ve invented, take another shot of potato vodka—twelve so far this game, our second one of the night—I stand to hit the head and go all wobbly, spin, and kick the board over, and the game is undone, pieces clink and shoot across the marble floor and I too hit the floor, cool and hard, and laugh, realizing for the first time in a decade or more, I have been knocked slap out.

Gregori Rasputin, 42,

Mystic Religious Leader & Advisor to the Romanovs

H

ere is God’s own hand at beauty, this mystical black man in fur coat and Buddha cheek, full of grace and fury and quick of wit and smile, but he cannot drink to save his life let alone his race or country, and there on the chaise longue reclines his whore-wife, who takes each shot like the Lord’s own body, and my Ekaterina strokes her hair and they purr together there and it remains unspoken between us men that the winner shall take all—this fighter, so used to having his way with every man he battles and every woman he woos, which is just another kind of battle, has left his lady open and I slide my bishop, cocked at an angle, right up her side and pull her to my lip of the board and I pour his shot rim-high and he holds it like a prayer bead, steady as winter hail, and throws it down and blows out his spirit and shakes his head and topples—his deep eyes roll back in his head like those of my epileptic sister Maria as she floundered in the Tura River below our Siberian home, not a bird above nor a fish below but snow and snow and cold cold snow—when they pulled her out her lips were the Prussian blue of cyanide—like those of my brother Dmitri, who with me fell into that same river and only I escaped to live and thrive—now in the Russian winter the pale air that twists from my lips is but their spinning bodies come to invade me no matter how I’ve tried to snuff them out.I have always lived by this one creed: the greater the sin, the greater the redemption. It’s why I explained the pointlessness of flagellation to the Khlysty—if you are to deny the body, brother, why excite the senses with pain when there is so much

pleasure to be had—now beside his sleeping, snoring body I will have my way with his whore-wife and as I twist the long strands of my chin whiskers and pull them taut, the Lord begins to excite and shake my crystal bones, move through me, and make my tongue the trumpet of His good grace with which to sing a gospel into the great chasm of these very Mothers of God.

Lucille Cameron, 21,

Prostitute, Secretary, & Wife to Jack Johnson

A

fter that bitch lied on the stand, Jack skipped bail and we fled to a Mexican town where we could hear the church bells tolling all the way down to the beach where Jack and I, hand in hand, followed the mule tracks in the dry sand, the wind erasing them one grain at a time. We passed fishermen in wooden dinghies, which bobbed in the water like coffins; passed kids who flew kites made of yesterday’s newspapers; turned off at Calle Vida and entered the town’s only cemetery, where we joined the old women who wore pressed and austere gowns, white with embroidered roses and tangles of thorny stems. They swept dirt and salt off their loved ones’ crypts and put fresh-cut flowers and candles on top of brightly painted tombs—pinks and pale oranges, light blues and greens—like muted versions of the hump houses in our Paris on the Prairie. I pulled away and walked back among the poorest graves, some nothing more than ash in a mason jar or a lone crucifix stabbed into the earth. And then this one: a small pair of faded blue pants and a red and blue striped shirt, both folded sharp as surgical tools, held in place against the blowing wind by an ash-filled plastic bag, and like a lambskin condom, it had burst where a bone that didn’t quite burn had pushed through. I put my fingertip to it, pushed it back as gentle as you please, and brushed away the leaves and said a prayer to Mary for this dead child and for mine too, who’d be about size enough now to wear these clothes.Now sitting on this velour chair beneath crystal chandeliers that hang twenty feet above, I tamp the tears down,

because I know there’s no going back to Mexico, nor to the United States, nor to a time before that law was passed, before they needed a Great White Hope and found it only in the form of Uncle Sam; back before the operation or before my innocence was stolen by Uncle Ray’s wandering hands—there’s no back at all and there’s certainly no tomorrow—there is only the giving in to the moment—Ekaterina’s hand on my thigh, her lips and breath on my neck, the moan caught in my throat, and this bright-eyed mystic standing before me, worshipful and tugging his beard. My man is the king—he has scraped through this life by way of nimble violence, though he appreciates delicate things—my thin wrists, the tsar’s Fabergé eggs—the sheen of a simple pigeon feather can bring him to tears—but this night is not his night: it will see no rise from him at all.

Me and the Devil Blues: Johnson v. Trussle

In a Cutting-Heads Contest near Itta Bena, Mississippi,

August 13, 1938

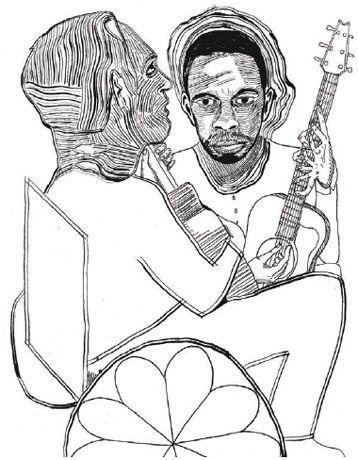

Robert Johnson, 27,

Author of Twenty-Nine Published Songs

N

ow I’m back in the Delta having fun and folly with the old fool, Charlie—sure I ran his name through some mud but just to bend his bones a bit—he got raw about it, pointed that fret-pressin’ knife at me, a simple threat from a simple gimp, and spoke up strong and stout and called me out to run guitars, ring notes from their necks, and I laughed and did a double take, couldn’t hardly believe my ears let alone my eyes ’cause they been bad since the day I’s born—reckon why I couldn’t recognize that white man for what he was, standing there at the crossroads where the low moon made a shade of him, like some beast in black clothes—he got me to hit the road, head out west to San Antone, where I stood in a studio facing peeling wallpaper and singing so soft they made me record each tune twice—I put my soul in them songs and he sold them by the thousands till they turned into tiny coffins holding dead tracks—when I play some roadhouse show people always beg I do exact as on that wax, you know, like I’s a jukebox built just for they pleasing, but to me that’s just a prison, and I am dead set against repeating myself like that damn clock ticking on the grade school wall above the picture of a lynched god, white as white cotton ever got, where I spent my days studyin’ how to jump a freight, didn’t wait to get put-behind no mule, hoeing up a row just to plod on back, so I quit that school and I quit this land and hobo’d a train north to Chicago, where I slept in cemeteries and sat on tombstones playing long enough that my fingers grew calluses so leather-thick I could grab a coal so quick out the fire and light my cig

before I’d even begin to feel its warmth—still I can’t shake the eerie notion that my life’s passing before my ears and eyes—but if I’m hell bound, Mama, I’m ready to go; let the devil’s hounds howl for me through the night.So play your best, Chuck, then step aside, ’cause I’m gonna cut you so swift and deep, you’ll spend the rest of your crippled life jaw-jacking ’bout how in this hell-hot weather you had your head severed by the damnedest bluesman ever.

Charlie “Trickle Creek” Trussle, 67,

Paraplegic & Unrecorded Slide Guitarist (Dedicated to Cedell Davis)

S

ay he done sold his soul to the devil but what could a whelp like this boy h’yer ever know about the real hell I been through, though I know good and goddamn well I ain’t got a snowball’s chance to beat him—his fingers nimble as spiders on a web, perfect as a pocket watch tick—still, what I’m supposed to do, take raw guff off this bragging rogue, let him disrespect me, call me Cripple Creek, as if having polio and being wheelchair-bound makes me less a man than him? Ain’t I throbbing with the same desire as any other body? But boy if my hands could bloom, flower like a fetus in womb, I’d make the tunes I hear in my head and shame this cur, smiling in pinstripes and plucking away. Instead, I scraped out bar chords and bullied short runs with this butter knife I stole from St. Anne’s Orphanage. And when he sings,

Hello, Satan, I believe it’s time to go

, I look down at the devil’s own doing: my claws; my fists curled tight into palsied balls, tight as when I’d crawl drunk into Lila’s lap as we lay in my cot out back of Manning’s Auto Repair, way back before she left on that Greyhound searching for someone to fill her with that baby she wanted; these same busted hands that could never hold still her steady rolling self, never mind the children we could not make.In a flash I bust through my impotent rage and ram this blade through Bob’s thick skull, but then I’m sober and awake again, sitting hangdog and silent, listening at him strum and pick and sing so goddamn beautiful it makes me want to cry.