The Book of Duels (20 page)

Authors: Michael Garriga

Witness: Rachel Jackson, 39,

Wife & Bigamist

M

ister Jackson has lit out for Kentucky again, lit out on horseback with friends again,

For business

, he said, but I am no fool: I know where he goes and I know what he gains—off to Philadelphia twice to be among the men who shape the world because he, who has yet to put seed in my womb and I imagine never will, has designs to lead this nation—he, who cares more for the snort of a horse than that of a cognac—Lord, I love him and I would defend him against an army of detractors with either wit or whip—why then did I dream last night that I followed him through the hardwood forests that grow aside the Tennessee River, riding our prized Truxton in the dew of the morning and sun-dappled noon—the azalea bushes in full bloom with wisteria vines married through, their long purple streams twining amid the pink plump tangles and blaring white blossoms and little flutter-byes twittered by and doves cooed their coos and where he stopped to water his horse the river kept its course, straight and true, when from the water a beast arose and came streaming ashore to stand before him and unfasten its fur which fell from its body as if it were robes to pool in the earth like the black fur rug that lies on our parlor floor and there standing before my husband, a naked Cherokee squaw—her eyes like almonds and honey, her hair a brunette river run over the cliffs of her shoulders—his hands go to her and the sun drops like a seed cone and darkness attends them and I watch now from my vantage high in an old hickory as they couple on the floor of the woods crying each other’s secret names and I weep and watch by light of full

moon, which shines on me, and they discover me there, weeping and swooning and naked, watching and watched.Now I pine away the morning, sitting on the stone steps looking over the planted estate where everything grows verdant and ripens. Our slaves go about picking fruits and hoeing earth, and one of them, Long Feather, is in the stable and his fine form, I think, comes from his mix of Creek and African blood. He will come to the out-kitchen soon for his lunch bucket of molasses and biscuit and ham, and Long Feather, whose hair is black as Truxton’s mane, will wear an odor of horse froth and oats, and he’ll lead Truxton to the back door and he’ll be saddled and Long Feather will lift me up and oh how I shall ride him.

Andrew Jackson, 39,

Ex-Senator, Judge, Major General, & Son of Scots Irish Immigrants

I

swear on my mother’s sweet soul I will blow him through, as certain as he has blown on my embers till the flames grew into an all-consuming fire that shall lay waste to any challenge before me, or any base fool like this poltroon here who uttered the vile calumny against my dear Rachel, a fierce bucking beauty herself—she can ride Truxton through town without even wearing her gloves, and if a man so much as speak her name I will tie him to the first tree, let alone one so base as to claim I’d made bigamy with her—I should have pistol-whipped this puppy when he first began his rumor-seeding but I knew him to be but a lickspittle in some other man’s fight—still, he is of British birth and so a born bastard and this Dickinson shall receive no less than what I have promised Mother to visit upon every man Jack soldier of that son of a whore, England, whose brutes killed both my brothers—one by bullet and one by exposure in a Carolina prison camp where they cut my cheek and poisoned Robert with vile tack slathered in rat grease—they drove sweet Mother to her early grave too—what I’d not give to see that woman again, to have her ease my burning brow with her cool hands and gray eyes, those bottomless pools of affection so alike to Rachel’s—I’d even let this rascal live so he could admire the morning fog as it settles among the pine needles—but that cannot be—there is only this one life, this one chance to alter the shape of the world, before we enter the eternal damnation of silence and utter darkness and she died in my

arms blessing the vengeance I swore on every lobsterback son of a bitch I could bury.The judge calls fire and before I can even aim, his ball cuts through my ribs and I hear the damn things break—I am dead, by God—I mash my mouth into a razor line, wheeze through my nose, and the sweat bursts in my eyes, near blinding me—I level the pistol and squeeze the trigger but the gun only half fires—my chin starts to tremble when the smell of Mother’s laundry lye overwhelms me and Rachel’s breath is on my neck and her hand comes over mine and steadies the gun and we re-cock the hammer together and pull the trigger and send our shot into his piss-proud belly and he shuffles back and flops to the ground, legs all aflail, and he has surely spent his last day on earth and my blood runs down my body but I am alive, and because I am, so too is Mother, and Rachel besides, and we shall so remain until we all enter oblivion together.

Man above Challenge: Dauphin v. Culver

A First-Blood Duel with Colichemardes, behind the St. Louis Cathedral, New Orleans, Louisiana,

April 3, 1834

Speaker:

Tim-tim!Audience:

Bois sec

.Speaker:

Cassez-li

. . .Speaker and Audience together: . . .

dans tchu

(bonda)

macaque

.

Traditional Creole Call to Story, from Lafcadio Hearn’s

Gombo Zhèbes: Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs

Emile Dauphin, 19,

French Creole

H

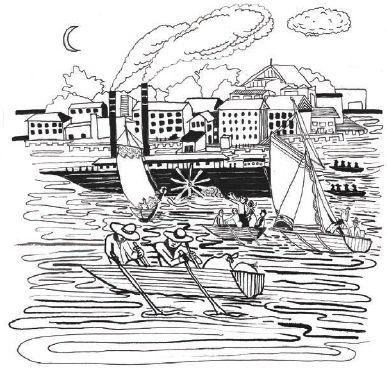

e should not have crossed Canal and into our Quarter, nor entered the octoroon ball and defiled it with his odious taint, like too much choupique at the Bienville Market. These Kaintock keelboat rats have done much to damage our town—set fire to the Tchoupitoulas Street Fair where Papa kept his cattle and killed Monsieur Gaetano’s dancing bear in his Congo Square circus. He is indeed beneath my birth, yet I feel the need to lash and strike this boorish tramp who approached sweet Yvonne, whose sister I keep in a clean white cottage on Rue Rampart, and pulled her hand from Jean Philip’s and barked back the timid boy, affrighted I suppose by stories of Wild Bill Sedley and other riverboat bullies. He would not heed my call so I demanded his blood from my blow, or he could have mine in turn, and though his shoulders are thick as any field Negro’s, I possess the skills—two full seasons under the tutelage of Garland Croquere, my

maitres d’armes

, the swiftest mulatto you ever saw, but whom I have surely outgrown, and he will see so in my stance and in the grace with which I dispatch this ruffian—tomorrow

mes amis

in cafes will sing how deftly I did defeat our enemy.We cross on cypress boards laid in the pitch mud, two Negroes before us with lighted flambeaux to see our way to St. Anthony’s Park, hidden from sight by the bustling gowns of Spanish moss, and I recall when I was but fourteen and walking this very banquette, a Kaintock and I came to an impasse until our eyes met and I acquiesced and stepped down into the muck, and though I was loath to look back, when

I did I saw that Papa had moved off as well—I wish he could see me now as I strike this oaf and his blood runs down his lips and onto his filthy fingertips, the ones he rubbed on sweet Yvonne’s thin wrists and she did not even flinch at his gaucherie, but now I have my honor and I will retrieve her as my own reward—Jean Philip be damned.

Dale Culver, 23,

Riverboat Kaintock

I

seen this purty half-breed gal, covered in cream-colored lace, dancing with some princey French fool and so stiffened my back paddleboard straight and said,

Scuse me now, son, but I’m cutting on in

, but I really wanted to knock hell out that sissy and flang that gal over my shoulder like a fifty-pound sack of sugar and skidaddle with her back to the keelboat and if I had to fight off the boys who’d try to make sport of her, well I’d holler em back with my fists and the trusty blade I keep in my boot, shouting,

I’m a man made of anvil and alligator, been weaned on wolf milk and whiskey; got dynamite for a heart and snake spit for blood; any man what touch my gal will count himself lucky not to wake with his ears missing or an eye gouged out or his tongue torn from his flappy jaw

, when this other little dandy here pokes me in the chest and says he’s her escort—he is, him—what goes the size of a bantam pullet I’ve lost money on, and me with red turkey feather in cap to show I’m the bully of my boat, been hauling on a cordelle and pulling the sweeps since I was twelve, so I laughed in his face but he just up and took my nose between his knuckles and twisted and ever last one of them Frenchies stepped back and even the musicians stopped they song, and buddy boy, I knew the score—but before I could call,

Put up your dukes

, he says to me,

Sir, let us as gentlemen satisfy our honor

, but I have absolute no use for this dumb show of dignity—what good is your honor, man, when you are dead and in the grave?Yet here I am, tightening my grip till my knuckles burn white ’round the handle of this wooden sword, blood pounding in my barking-mad mind, and I surge to strike and bash

this boy’s head but the Nongela rye’s got me bandy-leg’d as the first time I ever took to a boat, so I rise and swing and stumble again, and he taps my noggin and splits my bottom lip clean in two like a pig’s hoof and he says,

It is done; let us repair

, and turns his back to me but I am not done: I slip out the sweet steel I’ve carried all the way from Louisville to fend off pirates and bushwhackers—you wanted some of my blood, boy, but I will take all of yours.