The Book of Duels (7 page)

Authors: Michael Garriga

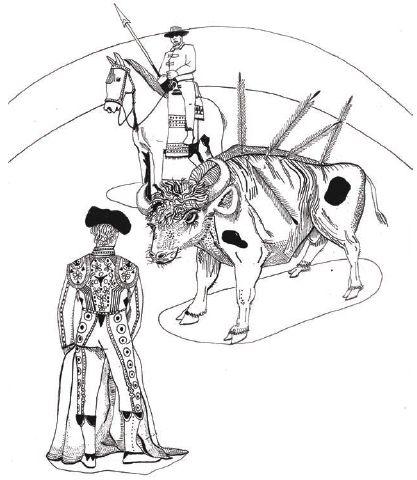

Sueño de Fuego, 5, 584 Kilos,

Miura Bull from La Ganadería Miura Lineage

S

cratch and snort and huff and puff and put my hoof-print in this earth—this my place and this my time and here I’ve come to fuck or fight—here I find no cow nor steer to my delight, so stomp and spit and huff and thrust and put my rut in this beast here—six legs, it has, three arms, two heads—has it come to muscle me, to make a morsel out of me—but truth be told, I want it more, so I drive my horn straight through its torso, and even as it barbs my hide, I lift it from the earth, shift my hump and dump it rump-wise and tear its insides out—I stomp and bellow, grumble and dig and suffer as it dies.Jabbed and hooked four men today and drove them each and all away—they barbed and barbed but I drove them each away—now comes their god, skin of shiny lights, who cries and spins and shouts and hides behind a bright red cape that goes a swishy sway, and it ripples like heifer scruff when I mount and huff and puff and grunt my calf-make rut—I rush and rush but it twirls and I spin and crash and fall again until the red is me running from my snoring snout and coming in strings from my open mouth—still the cape goes wiggle waggle more—I rake my hoof and miss my mark and grunt and puff and thrust my horn twice more into earth, holes each the size of this god’s waist—about me roars the horde who wave their small white rags and shriek for ears and tail and more—

Toro

, he cries and

Toro

, again—and my wind blows out the holes in me and so too goes my blood—I cannot lift my head, I am bone-rattled and beaten, defeated in battle—and now my nape lies smooth, my tense muscles unknot—I’ll soon be leaving this body behind,

rise over the moon to the Great Pasture beyond, in time to join my harem of grazing long-lashed gals who will swoon and low when they gaze at me and raise their swishy tails.Toro

, he calls again, and though my mouth is slick with blood, I will not show my tongue nor shake the sticks stuck near my spine; no, let them whistle till their lips go numb but I will bristle at dirt no more nor snort nor snore nor warn nor bluff, but wait till time is mine and true and ripe with proof, and then, horns low, I will charge.

Ignacio Lopez y Avaloz, 31, 64 Kilos,

Famed Matador from Priego de Córdoba

I

urge the bull to meet my half-cocked thrust and bravely die same as he fought but now he balks and so we stare like the last two lovers alive, each facing death without the other: Oh Lord, bring this noble beast to rest before my feet and tonight I will spread Your word to the heathen women of Granada, passing my tongue through their plump lips as if they were plucked rose petals pressed between the pages of Your book.

Toro, toro

, I call yet he does not move, though I have twisted him in pass upon pass, spinning blood from his hump to freckle the ochre earth, packed hard as my cock I sacrifice to virgins who come nightly to cool my nerves, which thrum as did the organs of La Catedral de Santa María when I was but a babe and wiry and ill-behaved, wriggling in Mama’s lap, and the music bellowed through the open mouths of pipes as large as lances and I would shriek, a sound lost among the din, and she would rub my face with the soft skin of her hands yet deny me suckle again and again and I’d cry the more demanding milk, my earnest hunger never filled. I set my jaw and stamp my foot and holler yet again,

Toro!The drums roll and the horns swell and the bull comes and I cross before him, sword straight out, but he swings his head at me, unbinds me from the earth, and my mouth goes dry as silenced organ pipes and the world becomes a singular hiss, as when Mary’s milk missed the saint’s lips and scalded on a searing stone, and I smack against the ground and the air explodes from my lungs and back and a fire burns riot through my guts while I try to suck and suck and suck—

Jose “Pepe” Hernandez, 33, 61 Kilos,

Ferdinand’s

Mozo de Espadas

from ValenciaI

gnacio poses before his bull like Saint George above his dragon and he lays the Toledo steel estoque across the blood-red muleta, which the wind catches and flaps about, exposing his thighs—I should have soaked the flannel cape, put more weight on its hem against the whipping of this weird wind but now I’m lost in his paso doble: the man and his cape and the bull in his cape form an ephemeral statue that spins painfully slow and tight, the blood of the bull brushes a streak across the gold-threaded buttons, which I fastened for Ignacio not two hours ago when I’d sewn him into his pants and plaited his hair, pinning it beneath his felt montera—as I knelt before him buffing his shoes, I looked up and caught the pity in his eyes, as if he and I had not once competed for top purses until I was gored by a bull, leaving me instead a cripple who will never fight another bull nor carry the full Fiesta de Semana Santa bier again—the bull charges Ignacio and as one mouth the arena gasps and I am a child in the old caves at the beach, where the waves broke against the vaulted rocks, the water receding and sucking the air out with it, tugging the breath from my young lungs, and I stood shocked-still and numb until the next wave came with cold spray and brought my senses back—the bull has buried his horn hilt-deep in the belly of Ignacio and he is as dead as this bull soon will be, his body dragged by horse and rope from

plaza

to

matadero

where his head will be removed, hide stripped, meat butchered, shipped to market, and sold to people still mourning the loss of Ignacio, who will have his own body

hoisted onto the shoulders of toreadors who will bear him to Catedral de la Encarnación, where he will lie in repose five days and nights lit dimly by candle for pilgrims come the world over to kneel by the hundreds and thousands and smear their tears and fingerprints across his glass coffin, covering it with roses and rosaries, and wail as he’s carried to the Cuevas de Sacromonte and buried there in full regalia—people will speak of him in cafes, will read of him every Easter in newspapers, will name their children after him, and some will even come to worship him as we both did Romero.But I will simply sew a black brassard about my right sleeve and limp on to a new torero, whom I will dress and assist and hold his estoque and muleta, which I will wet so that it hangs heavy enough to hide him from the eyes of the bull.

Night of the Chicken Run: Summers v. Scarborough

Dueling Cars on a Dirt Road between Fields of Garlic, Gilroy, California,

June 2, 1967

Charles “Chaz” Summers, 18,

Driving His Father’s 1965 Thunderbird

B

ad enough Sara had to neck on this greaser with a duck-butt haircut from another time but did she have to do it behind the gym while wearing my letterman jacket—that’s what her girlfriends told me and that’s what drove me mad—I couldn’t just bust his face with fists, that would be like hitting him on the football field, where I ruled as middle linebacker knocking hell out of crossing receivers, catching their ribs and stealing their breath, until we played the Fresno Warriors and that cheap shot garbled my knee to goo, and so went the season and my scholarship, too, though Sara’s still leaving this fall—in spite of my Brooks Brothers chinos and bleeding madras shirts, despite that my old man owns these fields and the largest mill in town—my folks won’t come off with that kind of cash, no matter how good a school Stanford is—so this field will be my life and each summer I will wait for the garlic leaves to brown and die and then I will harvest and store the bulbs as well—surely this is the place where I will die or over in the mill, boxing stinking roses for someone else to eat—yet even after the surgery, when I’d see her in my jacket, my pride would swell, the way her hair fell straight over the big blue

G

—she’s leaving next week, rubbing it in my face with this hood rat here—I know I shouldn’t have slapped her at the pre-grad bash but I was cranked up and drunk and she was going on about the scene and saying,

Dig it, man

, like Maynard G. Krebs, high on grass—the politics and the music and the war and all that—I could have let it all pass except tonight I saw them in the back of his car, dry-humping to that hippie-dip music—it was my dad

who taught me how to truly hurt a man—crush his body or take his pride—so I called the dirt leg out to this dim lane to put his nerve and ride on the line—now I’m in my dad’s T-bird with power everything to show Sara one last time that I’m her man and that this could still be our summer of love.Bouncing in the light of his one good beam, rushing to meet him head-on as in some anxious dream in which there’s no waking nor escape, I’m lost in a fog thick as pigskin and I can’t find Sara.

Sara!

I scream,

Sara!

and I veer left at the last second and hit the ditch and the coil springs collapse and flex and I am airborne, weightless as a ball tossed across the middle of a football field.