The Clockwork Universe (2 page)

Read The Clockwork Universe Online

Authors: Edward Dolnick

A stranger to the city who happened to see the parade of eager, chattering men disappearing into Thomas Gresham's mansion might have found himself at a loss. Who were these gentlemen in their powdered wigs, knee breeches, and linen cravats? It was too early in the day for a concert or a party, and this was hardly the setting for a bull-baiting or a prizefight.

With its shouting coachmen, reeking dunghills, and grit-choked air, London assaulted every sense, but these mysterious men seemed not to notice. Locals, then, for the giant metropolis left newcomers reeling. The men at Gresham's looked a bit like a theater crowdâand with the Puritans out of power and Oliver Cromwell's head on a pole in front of Westminster Hall, theaters

had

opened their doors again. But in that case where were the women? Perhaps the imposing building on the fashionable street concealed a gentlemen's gambling club? A high-class brothel?

Even a peek through a coal-grimed window might not have helped much. Amid the bustle, one man seemed to be spilling powder onto the tabletop and arranging it into a pattern. The man standing next to him held something between his fingers, small and dark and twitching.

The world would eventually learn the identity of these mysterious men. They called themselves natural philosophers, and they had banded together to sort out the workings of everything from pigeons to planets. They shared little but curiosity. At the center of the group stood tall, skeletally thin Robert Boyle, an aristocrat whose father was one of Britain's richest men. Boyle maintained

three

splendid private laboratories, one at each of his homes. Mild-mannered and unworldly, Boyle spent his days contemplating the mysteries of nature, the glories of God, and home remedies for an endless list of real and imaginary ills.

If Boyle was around, Robert Hooke was sure to be nearby. Hooke was hunched and fidgetyâ“low of stature and always very pale”âbut he was tireless and brilliant, and he could build anything. For the past five years he had worked as Boyle's assistant, cobbling together equipment and designing experiments. Hooke was as bad-tempered and sharp-tongued as Boyle was genial. To propose an idea was to hear that Hooke had thought of it first; to challenge his claim was to make a lifelong enemy. But few questioned the magic in his hands. Hooke's latest coup was a glass vessel that could be pumped empty of air. What would happen if you put a candle inside? a mouse? a man?

The small, birdlike man was Hooke's closest friend, the lu

dicrously versatile Christopher Wren. Ideas tumbled from him like coins from a conjuror's fingertips. Posterity would know Wren as the most celebrated architect in English history, but he was renowned as an astronomer and a mathematician before

he sketched his first building. Everything came easily to this

charmed and charming creature. Early on an admirer proclaimed Wren a “miracle of youth,” and he would live to ninety-one and scarcely pause for breath along the way. Wren built telescopes,

microscopes, and barometers; he tinkered with designs for

submarines; he built a transparent beehive (to see what the bees

were up to) and a writing gizmo for making copies, with two pens connected by a wooden arm; he built St. Paul's Cathedral.

The Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge, the formal name of this grab-bag collection of geniuses, misfits, and eccentrics, was by most accounts the first official scientific organization in the world. In these early days almost any scientific question one might ask inspired blank stares or passionate debateâWhy does fire burn? How do mountains rise? Why do rocks fall?

The men of the Royal Society were not the world's first scientists. Titans like Descartes, Kepler, and Galileo, among many others, had done monumental work long before. But to a great extent those pioneering figures had been lone geniuses. With the rise of the Royal Societyâand allowing for the colossal exception of Isaac Newtonâthe story of early science would have more to do with collaboration than with solitary contemplation.

Newton did not attend the Society's earliest meetings, though he was destined one day to serve as its president (he would rule like a dictator). In 1660 he was only seventeen, an unhappy young man languishing on his mother's farm. Soon he would head off to begin his undergraduate career, at Cambridge, but even there he would draw scarcely any notice. In time he would become the first scientific celebrity, the Einstein of his day.

No one would ever know what to make of him. One of history's strangest figures, Newton was “the most fearful, cautious, and suspicious Temper that I ever knew,” in the judgment of one contemporary. He would spend his life in secrecy and solitude and die, at eighty-four, a virgin. High-strung to the point of paranoia, he teetered always on the brink of madness. At least once he would fall over the brink.

In temperament Newton had little enough in common with the other men of the Royal Society. But all the early scientists shared a mental landscape. They all lived precariously between two worlds, the medieval one they had grown up in and a new one they had only glimpsed. These were brilliant, ambitious, confused, conflicted men. They believed in angels and alchemy and the devil,

and

they believed that the universe followed precise, mathematical laws.

In time they would fling open the gates to the modern world.

Scientists in the 1600s had set out to find the eternal laws that govern the universe, but the world they lived in was marked by precariousness.

2

Death struck often, and at random. “Any cold might be the forerunner of a terminal fever,” one historian remarks, “and the simplest cut could lead to a fatal infection.” Children died in droves, but no one was safe. Even for the nobility, life expectancy was only about thirty. Adults in their twenties, thirties, and forties dropped dead out of the blue, leaving their families in desperation.

London was so disease-ridden that deaths outnumbered births; only the constant influx of newcomers disguised that melancholy fact. Medical knowledge was almost nonexistent, and doctors were more likely to harm their patients than to heal them. Those who fell ill could do little more than choose from a reeking cupboard of quack remedies. One treatment for gout called for “puppy boiled up with cucumber, rue and juniper.” As

late as 1699 the Royal Society was still debating the health

benefits from “cows piss drank to about a pint.”

The main alternative was woeful resignation. “I have had the misfortune of losing my dear child Johney he died last week of a feaver,” a woman named Sarah Smyter wrote in a letter in 1717. “It tis a great trouble to me but these misfortunes we must submit to.”

The mighty had no better options than the lowly. Many times they were worse off, because they were more likely to face a doctor's attentions. When Charles II suffered a stroke in 1685, his doctors “tortured him,” one historian later wrote, “like an Indian at a stake.” First the royal physicians drained the king of two cups of blood. Next they administered an enema, a purgative, and a dose of sneezing powder. They drained another cup of blood, still to no effect. They rubbed an ointment of pigeon dung and powdered pearls onto the royal feet. They seared the king's shaved skull and bare feet with red-hot irons. Nothing helped, and the king fell into convulsions. Doctors prepared a potion whose principal ingredient was “forty drops of extract of human skull.” After four days Charles died.

Two killers inspired more fear than any others. One was plague, the other fire. Both killed swiftly and in huge numbers, but in different manners. Plague leaped stealthily from victim to victim. Its mystery made for its horror. “For what is the cause that this pestilence is so greatly in one part of the land, and not another?” one panicky writer had asked during an earlier epidemic. “And in the same citie and towne why is it in one part, or in one house, and not in another? and in the same house, why is it upon one, and not upon all the rest?”

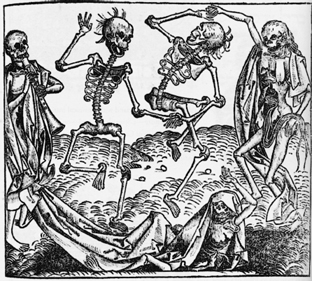

Dance of the Skeletons

(1493)

Fire had scarcely any mystery about it. It terrified precisely because it killed spectacularly, mercilessly, and in plain view. In crowded, cramped cities built of wood and lit by flame, it was all but inevitable that somewhere a hot coal would fall from a stove or a furnace, or a candle would tumble against a curtain or onto a pile of straw. Once escaped, even a small fire could blaze up into an inferno that sped along like a leaping, crackling tsunami. Its desperate victims raced for their lives down one twisting alley after another, fleeing round this corner and down that street, trying to outrun a pursuer that grew ever more powerful as the chase continued.

The dread that these ancient enemies inspired never died away, for everyone knew that no lull could be counted on to last. Nor did anyone think of fire and plague as natural calamities, the way we think of earthquakes and volcanoes. The seventeenth century was God-fearing in the most literal sense. Natural disasters were divine messages, warnings to sinful mankind to change its ways lest an angry and impatient God unleash still further rounds of punishment. Even today insurance claims refer to earthquakes and floods as “acts of God.” In the 1600s and long beyond, our ancestors invoked the same phrase, but they spoke of God's mysterious will with fright and cowering awe.

* * *

In that harsh age religion focused far more on damnation than on consolation. For scientists and intellectuals pondering the course of the universe and for the common man as well, fear of God shaped every aspect of thought. To study the world was to ponder God's plan, and that was daunting work.

Today

damn

and

hell

are the mildest of oaths, suitable responses to a stubbed toe or a spilled drink. For our forebears, the prospect of being damned to hell was vivid and horrifying. “People lived in continual terror of what they were told awaited them after death,” wrote the historian Morris Kline. “Priests and ministers affirmed that nearly everyone went to hell after death, and described in greatest detail the hideous, unbearable tortures that awaited the eternally damned. Boiling brimstone and intense flames burned victims who, nevertheless, were not consumed but continued to suffer these unabating tortures. God was presented not as the savior but as the scourge of mankind, the power who had fashioned hell and the tortures herein and who consigned people to it, confining His affection to only a small section of His flock. Christians were urged to spend their time meditating upon eternal damnation in order to prepare themselves for life after death.”

God, who knew all the details of how the future would unroll, had decided already who would be saved and who pun

ished. He would not be bartered with. Whether a person led a good life or a depraved one would do nothing to alter God's ver

dict; to say otherwise would imply that lowly man could direct all-powerful God.

A book called

The Day of Doom

appeared in 1662, the same year the Royal Society received its formal charter, and explained such doctrines in verse. A huge success (it became the first best-seller in America), it dealt curtly with such matters as infants condemned to the flames of hell:

But get away without delay

Christ pities not your cry:

Depart to Hell, there may you yell,

And roar eternally.

Children learned these poems by heart. Eventually such views would prove too grim to prevail, but they lasted well into the 1700s. Jonathan Edwards lambasted New England congregations with his most famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” as late as 1741. “The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked: his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else but to be cast into the fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in his sight; you are ten thousand times more abominable in his eyes than the most hateful venomous serpent is in ours.”

This was standard doctrine. Worship of God began with acknowledging His might in contrast with human puniness. “Those are my best days when I shake with fear,” John Donne declared. Few sins were too small to bring down God's wrath and to stir up soul-wrenching guilt. At age nineteen, in that same Royal Society year of 1662, Isaac Newton compiled a list of the sins he had committed in his life thus far. The tally, supposedly complete, listed fifty-eight items. Thoughts and acts were jumbled together, the one as bad as the other. One or two entries catch the eyeâ“Threatening my father and mother Smith [i.e., Newton's mother and stepfather] to burne them and the house over them”âbut nearly all the list is mundane. “Making a mousetrap on Thy day.” “Punching my sister.” “Using Wilford's towel to spare my owne.” “Having uncleane thoughts words and actions and dreamese.” “Making pies on Sunday night.” These sins may strike us as minor and commonplace. In Newton's eyes, they were deeply shameful betrayals of himself and his God.

In this self-lacerating respect, at least, Newton was far from unique. The writer and theologian Isaac Watts, who would grow up to compose such hymns as “Joy to the World,” first revealed his talent in an acrostic he composed as a young boy, in the late seventeenth century. It began:

I

am a vile polluted lump of earth

S

o I've continued ever since my birth,

A

lthough Jehovah grace does daily give me,

A

s sure this monster Satan will deceive me,

C

ome therefore, Lord, from Satan's claws relieve me.

A second verse spelled out similar thoughts for the name Watts

.