The Clockwork Universe (4 page)

Read The Clockwork Universe Online

Authors: Edward Dolnick

The authorities flailed about in search of a solution. Plays,

bull-baitings, and other entertainments were banned, because plague was known to be a disease of crowds. Was it the poor who carried this disease? The lord mayor tried to restrict the movements of the “Multitude of Rogues and wandering Beggars that swarm in every place about the City, being a great cause of

the spreading of the Infection.” Were animals the culprits? In the

summer of 1665, the authorities called for the immediate killing of all cats and dogs. Orders went out to Londoners to kill “all their dogs of what sort or kind before Thursday next at ye furthest.”

6

Thousands upon thousands of cats and dogs were killed. The result was to send the rat population soaring.

Nothing helped. Throughout the summer panicky crowds

bent on escaping the contaminated city clogged the roads out of London. The poor stayed put. They had no money for travel and no place to go, but the rich and the merely well-to-doâdoctors, lawyers, clergymen, and merchantsâshoved their way into the scrum. Coaches and carriages knocked against one another, their horses pawing the mud, while heavy-laden wagons fought for position. The frenzied pack fighting through the narrow streets

reminded one eyewitness of a terrified crowd in a burning theater.

Some fled toward the Thames and tried to commandeer fishing boats, anything that could float and take them to safety. Those who managed to escape the city had to brave the residents of the countryside, who greeted the refugees with clubs and muskets.

The king and his brother, the Duke of York, fled London in early July. Most of the Royal Society had scattered by then, too, looking forward to a time “when we have purged our foul sins and this horrible evil will cease.” Pepys sent his family away, but he himself retreated only as far as Greenwich. At the end of August he ventured on a long walk in the city. “Thus the month ends,” he wrote, “with the plague everywhere through the Kingdom almost. Every day sadder and sadder news of its increase.” In the last week of August, Pepys wrote, plague had claimed 6,102 lives in London alone.

Worse was to come.

September 1665 unnerved even Pepys. “Little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells,” he lamented in a letter to a friend. (It was plague that had inspired John Donne to write, “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”)

By now, with so many dead and so many gone, frenzy had given way to desolation. Grass grew in the streets of London. In place of the usual clamor of voicesâstreet vendors had been banned, so newsboys and rat catchers and fish sellers no longer hawked their waresâsilence reigned. “I have stayed in the city till above 7,400 died in one week, and of them above 6,000 of the plague,” Pepys wrote, “and little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells; till I could walk Lombard Street and not meet twenty persons from one end to the other . . . ; till whole families, ten and twelve together, have been swept away.”

Now there were too many dead for individual burials. At night death carts rattled along empty streets in search of bodies, the darkness penetrated only by flickering, yellow torchlights. Cries of “Bring out your dead!” echoed mournfully. But with death striking willy-nilly, there were too few men left to drive the carts, too few priests to pray over the victims, too few laborers to dig their graves. The carts made their way to mass burial pits and spilled in their cargo. Many Englishmen recalled the somber words of King Edward III, eyewitness to the horrific epidemic of an earlier day. “A just God now visits the sons of men and lashes the world.”

And then, mysteriously and blessedly, it ended. In mid-October, Pepys reported six hundred fewer deaths than the week before. The survivors began the gloomy process of taking stock. “But Lord, how empty the streets are, and melancholy,” wrote Pepys, “so many poor sick people in the streets, full of sores, and so many sad stories overheard as I walk, everybody talking of this man dead and that man sick, and so many in this place, and so many in that.”

By the end of November 1665, people began to flock back to

London. Within another month the epidemic had all but ended.

The plague had claimed one-fifth of the city's population, a total of one hundred thousand lives.

Plague hit London harder than anywhere else, but all England had suffered. In some cases, as in the famous calamity in the village of Eyam, the cause could be pinpointed. In September 1665 a village resident named George Vicars opened a box. Someone in London had sent a gift. Vicars found a packet of used clothing, felt it was damp, and hung it before the fire to dry. The clothing was flea-infested. In two days Vicars was delirious, in four dead. The disease spread, but the local rector persuaded the villagers it would be futile to leave and dangerous to others besides. Outsiders left provisions at the village outskirts. The plague took a year to burn its way through Eyam. In the end, 267 of the village's 350 residents lay dead. (The rector who refused to flee, Reverend Mompesson, survived, but his wife did not.)

Nearly always, though, plague seemed to rise out of nowhere, like some ghostly poison. The university town of Cambridge, which had weathered several epidemics through the centuries, had a long-established policy in place. (Builders would one day unearth mass graves beneath the idyllic grounds.) When plague

settled onto the town, the university shut down and sent its stu

dents and faculty away, to wait for a time when it would be safe

to gather in groups again. In June 1665 plague struck Cambridge,

and the university closed.

A young student named Isaac Newton gathered up his books and retreated to his mother's farm to think in solitude.

In the fateful year of 1666, a second calamity struck London. Perhaps God had

not

forgiven sinful mankind, after all. Perhaps those who had prophesied that the world would end in all-consuming fire had been right all along. Plague had been insidious and creeping; the new disaster was impossible to miss. But the Great Plague and the Great Fire had one similarity that

outweighed the differences between them. Both were the work of

an outraged God whose patience was plainly drawing to a close.

The fire burned out of control for four days, starting in the slums near London Bridge and quickly threatening great swaths of the city. One hundred thousand people were left homeless. Scores of churches burned to the ground. Iron bars in prison cells melted. The stunned survivors stumbled through the ruins of their smoldering capital and gazed in horror. Where a great city had stood just days before, one eyewitness lamented, “there is nothing to be seen but heaps of stones.”

As for who had started the fire, everyone had a theory. Catho

lics had burned the city down, to weaken the Protestant hold on power. Foreigners had done it, out of envy and malice. The

Dutch had done it, because Holland and England were at war, or

the French had, because the French and the Dutch were allies. The king himself even figured in the rumorsâhe was, people whispered, a monarch filled with hatred for London (which had clamored for his father's execution) and obsessed with building monuments to himself. What vengeance could compare with destroying the home of his enemies and then rebuilding it to suit his own taste?

But all such explanations were, in a sense, beside the point. To focus on who had set the fire was a mistake akin to confusing the symptoms of a disease with the illness itself. Any such calamity reflected the will of God. The proper question was not what tool God had seen fit to employ, but what had stirred his wrath. In any case, even the best of investigations would yield merely what Robert Boyle called “second causes.” God remained the inscrutable “first cause” of everything. He had imposed laws on nature when he had created heaven and Earth, and ever afterward he had been free to change those laws or suspend them or to intervene in the world however he saw fit.

The fire began in the early hours of Sunday, September 2, 1666, in one of London's countless bakeshops. Thomas Farriner owned a bakery on Pudding Lane, deep in one of the mazes that made up London's crowded slums. He had a contract to supply ship's biscuits for the sailors fighting the Dutch. On Saturday night Farriner raked the coals in his ovens and went to bed. He woke to flames and smoke, his staircase afire.

Someone woke the lord mayor and told him that a blaze had started up near London Bridge. He made his way to the scene, reluctantly, and cast a disdainful eye at the puny flames. “Pish!” he said. “A woman might piss it out.”

At that point, perhaps, the damage might still have been

confined. But a gust of wind carried sparks and flame beyond Pudding Lane to the Star Inn on Fish Street Hill, where a pile of straw and hay in the courtyard caught fire.

Everything conspired to create a disaster. For nearly a year London had been suffering through a drought. The wooden city was dry and poised to explode in flames, like kindling ready for the match. Tools to fight the blaze were almost nonexistent, and the warren of tiny, twisting streets made access for would-be firefighters nearly impossible in any case. (On his inspection tour the lord mayor found that he could not squeeze his coach into Pudding Lane.) Pumps to throw water on the flames were clumsy, weak contraptions, if they could be located in the first place and if someone could manage to connect them to a source of water. Instead firefighters formed lines and passed along buckets filled at the Thames. The contents of a leather bucket flung into an inferno vanished with a hiss and sizzle, like drops of water on a hot skillet.

Making matters harder still, London was not just built of

wood but built in the most dangerous way possible. Rickety, slap

dash buildings leaned against one another like drunks clutching each other for support. On and on they twisted, an endless labyrinth of shops, tenements, and taverns with barely a gap to slow

the flames. Even on the opposite sides of an alleyway, gables tottered so near together that anyone could reach out and grab the hand of someone in the garret across the way. And since this was

a city of warehouses and shops, it was a city booby-trapped with heaps of coal, vats of oil, stacks of timber and cloth, all poised to stoke the flames.

The only real way to fight the fire was to demolish the intact buildings in its path, in the hope of starving it of fuel. As the fire roared, the king himself pitched in to help with the demolition work, standing ankle-deep in mud and water, tearing at the walls with spade in hand. Slung over his shoulder was a pouch filled with gold guineas, prizes for the men working with him.

Propelled by strong winds, the fire roared along and then split in two. One stream of flames headed into the heart of the city, the other toward the Thames and the warehouses that lined it. The river-bound fire leaped onto London Bridge, in those days covered with shops and tall, wooden houses. At the water's edge, the flames reached heights of fifty feet. Panicky refugees stumbled through the mud and begged boatmen to carry them away.

On the fire's second night Pepys watched in shock from a barge on the Thames, smoke stinging his eyes, showers of sparks threatening to set his clothes afire. As he watched, the flames grew until they formed one continuous arch of fire that looked to be a mile long. “A horrid noise the flames made,” Pepys wrote, and the crackling flames were only one note in a devil's chorus. People screamed in terror as they fled, blinded by smoke and ashes. House beams cracked like gunfire when they burned through. Hunks of roofs smashed to the ground with great, percussive thuds. Stones from church walls exploded, as if they had been flung into a furnace.

Through the next day things grew worse. “God grant mine eyes may never behold the like, who now saw above ten thousand houses all in one flame,” wrote the diarist John Evelyn. “The noise and cracking and thunder of the impetuous flames, the shrieking of women and children, the hurry of people, the fall of towers, houses and churches, was like a hideous storm . . . near two miles in length and one in breadth. Thus I left it, burning, a resemblance of Sodom or the Last Day.”

* * *

After four days, the wind finally weakened. For the first time, the demolition crewsâwho had resorted to blowing up houses with gunpowderâmanaged to corral the flames. As the fires burned down, Londoners surveyed the remnants of their city. Acre after acre was unrecognizable, the houses gone and even the pattern of roads and streets obliterated. People wandered in search of their homes, John Evelyn wrote, “like men in some dismal desert.”

One Londoner hurried to St. Paul's Cathedral, long one of the city's landmarks but now only rubble. “The ground was so hot as almost to scorch my shoes,” William Taswell wrote. The church walls had collapsed, and the bells and the metal areas of the roof had splashed onto the ground in molten puddles. Taswell loaded his pockets with scraps of bell metal as souvenirs.

Taswell was not the only visitor to St. Paul's. With their own homes destroyed, many Londoners had sought refuge in the huge, seemingly permanent cathedral. They found little but smoldering rocks. In desperate need of shelter, the refugees crawled inside the underground crypts and took their place alongside the dead.

The city itself lay silent and devastated. “Now nettles are growing, owls are screeching, thieves and cut-throats are lurking,” one witness cried out. “And terrible hath the voice of the Lord been, which hath been crying, yea roaring in the City, by these dreadful judgments of the Plague and Fire which he hath brought upon us.”

England's trembling citizens, it would eventually become clear, had the story exactly backward. The 1660s did not mark the end of time but the beginning of the modern age. We can hardly blame them for getting it wrongâthe earliest scientists looked out at a world that was filthy and chaotic, a riot of noise, confusion, and sudden, arbitrary death. The sounds that filled their ears were a mix of pigs squealing on city streets, knives shrieking against grinders' sharpening stones, and street musicians sawing away at their fiddles. The smells were dried sweat and cattle, with a background note of sewage. Chronic pain was all but universal. Medicine was useless, or worse.

Who could contemplate that chaos and see order?

And yet Isaac Newton turned his attention to the heavens and described a cosmos as perfectly proportioned as a Greek temple. John Ray, the most eminent naturalist of the age, focused on the living world and saw just as harmonious a picture. Every plant and animal provided yet another example of nature's perfect design. Gottfried Leibniz, the German philosopher destined to become Newton's greatest rival, took the widest view of all and reported the sunniest news. Leibniz took as his province Newton's stars and planets, Ray's insects and animals, and everything in between. The great philosopher surveyed the universe in all its variety and found, on every scale, an intricate, perfectly engineered mechanism. God had fashioned the best of all possible worlds.

One reason that seventeenth-century scientists had such faith was mundane. Much of the mayhem all around them went unheeded, like the noise of screeching brakes and whooping sirens on city streets today. But the crucial reasons ran deeper.

The founding fathers of science looked more or less like us, under their wigs, but they lived in a mental world nothing like ours. The point is not that they took for granted countless features of everyday life that we find horrifying or bewilderingâcriminals should be tortured in the city square and their bodies

cut in pieces and mounted prominently around town, as a

warning to others; an excursion to Bedlam to view the lunatics made for ideal entertainment; soldiers captured in wartime might spend the rest of their lives chained to a bench and rowing a galley.

The crucial differences lay deeper than any such roster of specifics can reveal. On even the broadest questions, our assumptions conflict with theirs. We honor Isaac Newton for his colossal contributions to science, for example, but he himself regarded science as only one of his interests and probably not the most important. The theory of gravity cut into the time he could devote to deciphering hidden messages in the book of Daniel. To Newton and all his contemporaries, that made perfect senseâthe heavens and the Earth were God's work, and the Bible was as well, and so all contained His secrets. To moderns, it is as if Shakespeare had given equal time to poetry and to penmanship, as if Michelangelo had put aside sculpture for basket weaving.

Look only at scientific questions, and the same gulf yawns. We take for granted, for instance, that we know more than our ancestors did, at least about technical matters. We may not have more insight into human nature than Homer, but unlike him we know that the moon is made of rock and pocked with craters. Newton and many of his peers, on the other hand, believed fervently that Pythagoras, Moses, Solomon, and other ancient sages had anticipated modern theories in every scientific and mathematical detail. Solomon and the others knew not only that the Earth orbited the sun, rather than vice versa, but they knew that the planets travel around the sun in elliptical orbits.

This picture of history was completely false, but Newton and many others had boundless faith in what they called “the wisdom of the ancients.” (The belief fit neatly with the doctrine that the world was in decline.) Newton went so far as to insist that ancient thinkers knew all about gravity, too, including the specifics of the law of universal gravitation, the very law that all the world considered Newton's greatest discovery.

God had revealed those truths long ago, but they had been lost. The ancient Egyptians and Hebrews had rediscovered them. So had the Greeks, and, now, so had Newton. The great thinkers of past ages had expressed their discoveries in cryptic language, to hide them from the unworthy, but Newton had cracked the code.

So Newton believed. The notion is both surprising and poignant. Isaac Newton was not only the supreme genius of modern times but also a man so jealous and bad-tempered that he exploded in fury at anyone who dared question him. He refused to speak to his rivals; he deleted all references to them from his published works; he hurled abuse at them even after their deaths.

But here was Newton arguing vehemently that his boldest insights had all been known thousands of years before his birth.

The belief in ancient wisdom was overshadowed by other doctrines. By far the most important of the seventeenth century's bedrock beliefs was this: the universe had been arranged by an all-knowing, all-powerful creator. Every aspect of the worldâwhy there is one sun and not two, why the ocean is salty, why lobster is delicious and deer are swift and gold is scarce, why one man died of plague but another survivedârepresented an explicit decision by God. We may not grasp the plan behind those decisions, we may see only disarray, but we can be certain that God ordained it all.

“All disorder,” wrote Alexander Pope, was “harmony not understood.” The world was an orderly text to those who knew how to read it, a tangle of blotches and squiggles to those who did not. God was the author of that text, and mankind's task was to study His creation, secure in the knowledge that every word and letter reflected divine purpose. “Things happen for a reason,” we tell one another nowadays, by way of consolation after a tragedy, but for our forebears

everything

happened for a reason. At the core, the reason was always the same: God had willed it.

7

God was a daily presence and used events great and smallâearthquakes, fires, victories in war, illness, a stumble on the stairsâto demonstrate his wrath or his mercy. To imply that anything in the world happened by chance or accident was to malign Him. One should not speak of “fate,” Oliver Cromwell had scolded, because it was “too paganish a word.”

God saw every sparrow that falls, but that was only for starters. If God were to relax his guard even for a moment, the entire world would immediately collapse into chaos and anarchy. The very plants in the garden would rebel against their “cold, dull, inactive life,” one Royal Society physician declared, and strive instead for “self motion” and “nobler actions.”

To a degree we can scarcely imagine, the 1600s were a God-drenched era. “People rarely thought of themselves as âhaving' or âbelonging to' a religion,” notes the cultural historian Jacques Barzun, “just as today nobody has âa physics'; there is only one and it is automatically taken to be the transcript of reality.” Atheism was literally unthinkable. In modern times, we presume that either God exists or He doesn't. We can fight about the evidence, but the statement itself seems perfectly clear, no different in principle from

either there are mountains on the moon or there are not.

In the seventeenth century no one reasoned that way. The idea that God might not exist made no sense. Even Blaise Pascal, one of the farthest-ranging thinkers who ever lived, declared flatly that it would be “absurd to affirm of an absolutely infinite and supremely perfect being” that He did not exist. The idea was meaningless. To raise the question would be to ponder an impossibility, like asking if today might come before yesterday.

For Newton and the other intellectuals of the day, God also had another aspect entirely. Not only had He created the universe and designed every last feature of every single object within it, not only did He continue to supervise His domain with an all-seeing, ever-vigilant eye. God was not merely a creator but a particular kind of creator. God was a mathematician.

That was new. The Greeks had exalted mathematical

knowledge above all others, but their gods had other concerns. Zeus was too busy chasing Hera to sit down with compass and ruler. Greek thinkers valued mathematics so highly for aesthetic and philosophical reasons, not religious ones. The great virtue of mathematics was that its truths alone were certain and inevitableâin any conceivable universe, a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, and so on.

8

In the Greek way of thinking, all other facts stood on shakier ground. A mountain might be precisely 10,257 feet tall, but it could just as well have been a foot higher or lower. To the Greeks, historical facts seemed contingent, too. Darius was king of the Persians, but he might have drowned as a young boy and never come to the throne at all. Even the facts of science had an accidental feel. Sugar is sweet, but there seemed no particular reason it could not have tasted sour. Only the truths of mathematics seemed tamper-proof. Not even God could make a circle with corners.

Seventeenth-century thinkers rejected the Greeks' distinction between truths that have to beâ

two and two make fourâ

and truths that happen to beâ

gold is soft and easy to scratch

. Since every facet of the universe reflected a choice made by God, chance had no role in the universe. The world was rational and orderly. “It just so happens” was impossible.

But the seventeenth century found its own reasons for regarding mathematics as the highest form of knowledge. The huge excitement among the new scientists was the discovery that the abstract mathematics that the Greeks had esteemed for its own sake turned out in fact to describe the physical world, both on Earth and in the heavens. On the face of it this was absurd. You might as well expect to hear that a newly discovered island had proved to be a perfect circle or a newfound mountain an exact pyramid.

Sometime around 300

B.C.

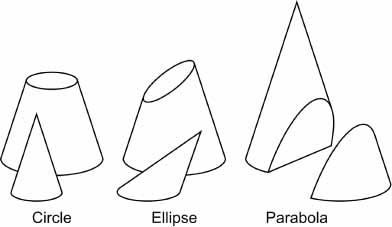

, Euclid and his fellow geometers had explored the different shapes you get if you slice a cone with a knife. Cut straight across and you get a circle; at an angle and you get an ellipse; parallel to one side, a parabola. Euclid had studied circles, ellipses, and parabolas because he found them beautiful, not useful. (In the Greek world, where manual labor was the domain of slaves, to label an idea “useful” would have been to sully it. Even to work as a tradesman or a shopkeeper was contemptible; Plato proposed that a free man who took such a job be subject to arrest.)

Nineteen centuries later, Galileo found the laws that govern falling objects on Earth. After he showed the way, the discoveries came in a flood. Rocks thrown in the air and arrows shot from a bow travel in parabolas, and comets and planets move along ellipses exactly as if a colossal diagram from Euclid had been set among the stars. The universe had been meticulously arranged, Galileo and Kepler and Newton demonstrated, and the arrangement was the work of a brilliant geometer.

Then came an amazing leap. It was not simply that one aspect of nature or another followed mathematical law; mathematics governed

every

aspect of the cosmos, from a pencil falling off

a

table to a planet wandering among the stars. Galileo and the

other seventeenth-century giants discovered a few golden threads

and inferred the existence of a broad and gorgeous tapestry.

If God was a mathematician, it went without saying that He was the most skilled of all mathematicians. And since nature's laws are God's handiwork, they must necessarily be flawlessâfew in number, compact, elegant, and perfectly meshed with one

another. “It is ye perfection of God's works that they are all

done with ye greatest simplicity,” Isaac Newton declared. “He is ye God of order and not of confusion.”

The primary mission that seventeenth-century science set itself was to find His laws. The problem was that someone would first have to invent a new kind of mathematics.