The Code Book (28 page)

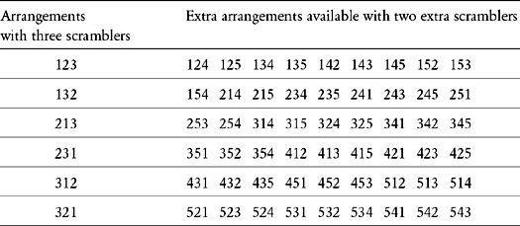

Rejewski’s skills eventually reached their limit in December 1938, when German cryptographers increased Enigma’s security. Enigma operators were all given two new scramblers, so that the scrambler arrangement might involve any three of the five available scramblers. Previously there were only three scramblers (labeled 1, 2 and 3) to choose from, and only six ways to arrange them, but now that there were two extra scramblers (labeled 4 and 5) to choose from, the number of arrangements rose to 60, as shown in

Table 10

. Rejewski’s first challenge was to work out the internal wirings of the two new scramblers. More worryingly, he also had to build ten times as many bombes, each representing a different scrambler arrangement. The sheer cost of building such a battery of bombes was fifteen times the Biuro’s entire annual equipment budget. The following month the situation worsened when the number of plugboard cables increased from six to ten. Instead of twelve letters being swapped before entering the scramblers, there were now twenty swapped letters. The number of possible keys increased to 159,000,000,000,000,000,000.

In 1938 Polish interceptions and decipherments had been at their peak, but by the beginning of 1939 the new scramblers and extra plugboard cables stemmed the flow of intelligence. Rejewski, who had pushed forward the boundaries of cryptanalysis in previous years, was confounded. He had proved that Enigma was not an unbreakable cipher, but without the resources required to check every scrambler setting he could not find the day key, and decipherment was impossible. Under such desperate circumstances Langer might have been tempted to hand over the keys that had been obtained by Schmidt, but the keys were no longer being delivered. Just before the introduction of the new scramblers, Schmidt had broken off contact with agent Rex. For seven years he had supplied keys which were superfluous because of Polish innovation. Now, just when the Poles needed the keys, they were no longer available.

The new invulnerability of Enigma was a devastating blow to Poland, because Enigma was not merely a means of communication, it was at the heart of Hitler’s blitzkrieg strategy. The concept of blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) involved rapid, intense, coordinated attack, which meant that large tank divisions would have to communicate with one another and with infantry and artillery. Furthermore, land forces would be backed up by air support from dive-bombing Stukas, which would rely on effective and secure communication between the front-line troops and the airfields. The ethos of blitzkrieg was “speed of attack through speed of communications.” If the Poles could not break Enigma, they had no hope of stopping the German onslaught, which was clearly only a matter of months away. Germany already occupied the Sudetenland, and on April 27, 1939, it withdrew from its nonaggression treaty with Poland. Hitler’s anti-Polish rhetoric became increasingly vitriolic. Langer was determined that if Poland was invaded, then its cryptanalytic breakthroughs, which had so far been kept secret from the Allies, should not be lost. If Poland could not benefit from Rejewski’s work, then at least the Allies should have the chance to try and build on it. Perhaps Britain and France, with their extra resources, could fully exploit the concept of the bombe.

Table 10

Possible arrangements with five scramblers.

Figure 43

General Heinz Guderian’s command post vehicle. An Enigma machine can be seen in use in the bottom left. (

photo credit 4.2

)

On June 30, Major Langer telegraphed his French and British counterparts, inviting them to Warsaw to discuss some urgent matters concerning Enigma. On July 24, senior French and British cryptanalysts arrived at the Biuro’s headquarters, not knowing quite what to expect. Langer ushered them into a room in which stood an object covered with a black cloth. He pulled away the cloth, dramatically revealing one of Rejewski’s bombes. The audience were astonished as they heard how Rejewski had been breaking Enigma for years. The Poles were a decade ahead of anybody else in the world. The French were particularly astonished, because the Polish work had been based on the results of French espionage. The French had handed the information from Schmidt to the Poles because they believed it to be of no value, but the Poles had proved them wrong.

As a final surprise, Langer offered the British and French two spare Enigma replicas and blueprints for the bombes, which were to be shipped in diplomatic bags to Paris. From there, on August 16, one of the Enigma machines was forwarded to London. It was smuggled across the Channel as part of the baggage of the playwright Sacha Guitry and his wife, the actress Yvonne Printemps, so as not to arouse the suspicion of German spies who would be monitoring the ports. Two weeks later, on September 1, Hitler invaded Poland and the war began.

The Geese that Never Cackled

For thirteen years the British and the French had assumed that the Enigma cipher was unbreakable, but now there was hope. The Polish revelations had demonstrated that the Enigma cipher was flawed, which boosted the morale of Allied cryptanalysts. Polish progress had ground to a halt on the introduction of the new scramblers and extra plugboard cables, but the fact remained that Enigma was no longer considered a perfect cipher.

The Polish breakthroughs also demonstrated to the Allies the value of employing mathematicians as codebreakers. In Britain, Room 40 had always been dominated by linguists and classicists, but now there was a concerted effort to balance the staff with mathematicians and scientists. They were recruited largely via the old-boy network, with those inside Room 40 contacting their former Oxford and Cambridge colleges. There was also an old-girl network which recruited women undergraduates from places such as Newnham College and Girton College, Cambridge.

The new recruits were not brought to Room 40 in London, but instead went to Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, the home of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), a newly formed codebreaking organization that was taking over from Room 40. Bletchley Park could house a much larger staff, which was important because a deluge of encrypted intercepts was expected as soon as the war started. During the First World War, Germany had transmitted two million words a month, but it was anticipated that the greater availability of radios in the Second World War could result in the transmission of two million words a day.

At the center of Bletchley Park was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion built by the nineteenth-century financier Sir Herbert Leon. The mansion, with its library, dining hall and ornate ballroom, provided the central administration for the whole of the Bletchley operation. Commander Alastair Denniston, the director of GC&CS, had a ground-floor office overlooking the gardens, a view that was soon spoiled by the erection of numerous huts. These makeshift wooden buildings housed the various codebreaking activities. For example, Hut 6 specialized in attacking the German Army’s Enigma communications. Hut 6 passed its decrypts to Hut 3, where intelligence operatives translated the messages, and attempted to exploit the information. Hut 8 specialized in the naval Enigma, and they passed their decrypts to Hut 4 for translation and intelligence gathering. Initially, Bletchley Park had a staff of only two hundred, but within five years the mansion and the huts would house seven thousand men and women.

Figure 44

In August 1939, Britain’s senior codebreakers visited Bletchley Park to assess its suitability as the site for the new Government Code and Cypher School. To avoid arousing suspicion from locals, they claimed to be part of Captain Ridley’s shooting party. (

photo credit 4.3

)

During the autumn of 1939, the scientists and mathematicians at Bletchley learned the intricacies of the Enigma cipher and rapidly mastered the Polish techniques. Bletchley had more staff and resources than the Polish Biuro Szyfrów, and were thus able to cope with the larger selection of scramblers and the fact that Enigma was now ten times harder to break. Every twenty-four hours the British codebreakers went through the same routine. At midnight, German Enigma operators would change to a new day key, at which point whatever breakthroughs Bletchley had achieved the previous day could no longer be used to decipher messages. The codebreakers now had to begin the task of trying to identify the new day key. It could take several hours, but as soon as they had discovered the Enigma settings for that day, the Bletchley staff could begin to decipher the German messages that had already accumulated, revealing information that was invaluable to the war effort.

Surprise is an invaluable weapon for a commander to have at his disposal. But if Bletchley could break into Enigma, German plans would become transparent and the British would be able to read the minds of the German High Command. If the British could pick up news of an imminent attack, they could send reinforcements or take evasive action. If they could decipher German discussions of their own weaknesses, the Allies would be able to focus their offensives. The Bletchley decipherments were of the utmost importance. For example, when Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in April 1940, Bletchley provided a detailed picture of German operations. Similarly, during the Battle of Britain, the cryptanalysts were able to give advance warning of bombing raids, including times and locations. They could also give continual updates on the state of the Luftwaffe, such as the number of planes that had been lost and the speed with which they were being replaced. Bletchley would send all this information to MI6 headquarters, who would forward it to the War Office, the Air Ministry and the Admiralty.

In between influencing the course of the war, the cryptanalysts occasionally found time to relax. According to Malcolm Muggeridge, who served in the secret service and visited Bletchley, rounders, a version of softball, was a favorite pastime:

Every day after luncheon when the weather was propitious the cipher crackers played rounders on the manor-house lawn, assuming the quasi-serious manner dons affect when engaged in activities likely to be regarded as frivolous or insignificant in comparison with their weightier studies. Thus they would dispute some point about the game with the same fervor as they might the question of free will or determinism, or whether the world began with a big bang or a process of continuing creation.