The Code Book (31 page)

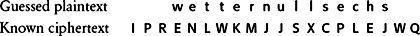

The first prototype bombe, christened

Victory

, arrived at Bletchley on March 14, 1940. The machine was put into operation immediately, but the initial results were less than satisfactory. The machine turned out to be much slower than expected, taking up to a week to find a particular key. There was a concerted effort to increase the bombe’s efficiency, and a modified design was submitted a few weeks later. It would take four more months to build the upgraded bombe. In the meantime, the cryptanalysts had to cope with the calamity they had anticipated. On May 1, 1940, the Germans changed their key exchange protocol. They no longer repeated the message key, and thereupon the number of successful Enigma decipherments dropped dramatically. The information blackout lasted until August 8, when the new bombe arrived. Christened

Agnus Dei

, or

Agnes

for short, this machine was to fulfill all Turing’s expectations.

Within eighteen months there were fifteen more bombes in operation, exploiting cribs, checking scrambler settings and revealing keys, each one clattering like a million knitting needles. If everything was going well, a bombe might find an Enigma key within an hour. Once the plugboard cablings and the scrambler settings (the message key) had been established for a particular message, it was easy to deduce the day key. All the other messages sent that same day could then be deciphered.

Even though the bombes represented a vital breakthrough in cryptanalysis, decipherment had not become a formality. There were many hurdles to overcome before the bombes could even begin to look for a key. For example, to operate a bombe you first needed a crib. The senior codebreakers would give cribs to the bombe operators, but there was no guarantee that the codebreakers had guessed the correct meaning of the ciphertext. And even if they did have the right crib, it might be in the wrong place—the cryptanalysts might have guessed that an encrypted message contained a certain phrase, but associated that phrase with the wrong piece of the ciphertext. However, there was a neat trick for checking whether a crib was in the correct position.

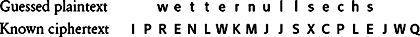

In the following crib, the cryptanalyst is confident that the plaintext is right, but he is not sure if he has matched it with the correct letters in the ciphertext.

One of the features of the Enigma machine was its inability to encipher a letter as itself, which was a consequence of the reflector. The letter a could never be enciphered as A, the letter b could never be enciphered as B, and so on. The particular crib above must therefore be misaligned, because the first e in wetter is matched with an E in the ciphertext. To find the correct alignment, we simply slide the plaintext and the ciphertext relative to each other until no letter is paired with itself. If we shift the plaintext one place to the left, the match still fails because this time the first s in sechs is matched with S in the ciphertext. However, if we shift the plaintext one place to the right there are no illegal encipherments. This crib is therefore likely to be in the right place, and could be used as the basis for a bombe decipherment:

The intelligence gathered at Bletchley was passed on to only the most senior military figures and selected members of the war cabinet. Winston Churchill was fully aware of the importance of the Bletchley decipherments, and on September 6, 1941, he visited the codebreakers. On meeting some of the cryptanalysts, he was surprised by the bizarre mixture of people who were providing him with such valuable information; in addition to the mathematicians and linguists, there was an authority on porcelain, a curator from the Prague Museum, the British chess champion and numerous bridge experts. Churchill muttered to Sir Stewart Menzies, head of the Secret Intelligence Service, “I told you to leave no stone unturned, but I didn’t expect you to take me so literally.” Despite the comment, he had a great fondness for the motley crew, calling them “the geese who laid golden eggs and never cackled.”

Figure 50

A bombe in action. (

photo credit 4.5

)

The visit was intended to boost the morale of the codebreakers by showing them that their work was appreciated at the very highest level. It also had the effect of giving Turing and his colleagues the confidence to approach Churchill directly when a crisis loomed. To make the most of the bombes, Turing needed more staff, but his requests had been blocked by Commander Edward Travis, who had taken over as Director of Bletchley, and who felt that he could not justify recruiting more people. On October 21, 1941, the cryptanalysts took the insubordinate step of ignoring Travis and writing directly to Churchill.

Dear Prime Minister,

Some weeks ago you paid us the honor of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the “bombes” for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention …

We are, Sir, Your obedient servants,

A.M. Turing

W.G. Welchman

C.H.O’D. Alexander

P.S. Milner-Barry

Churchill had no hesitation in responding. He immediately issued a memorandum to his principal staff officer:

ACTION THIS DAY

Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done.

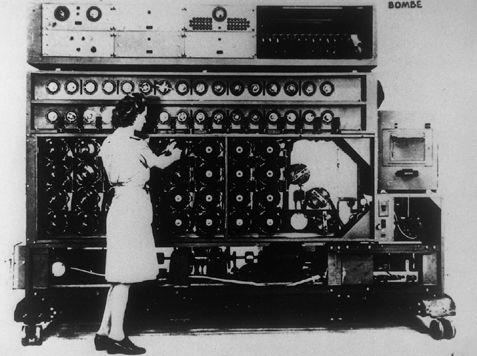

Figure 51

The

Daily Telegraph

crossword used as a test to recruit new codebreakers (the solution is in

Appendix H

). (

photo credit 4.6

)

Henceforth there were to be no more barriers to recruitment or materials. By the end of 1942 there were 49 bombes, and a new bombe station was opened at Gayhurst Manor, just north of Bletchley. As part of the recruitment drive, the Government Code and Cypher School placed a letter in the

Daily Telegraph

. They issued an anonymous challenge to its readers, asking if anybody could solve the newspaper’s crossword (

Figure 51

) in under 12 minutes. It was felt that crossword experts might also be good codebreakers, complementing the scientific minds that were already at Bletchley—but of course, none of this was mentioned in the newspaper. The 25 readers who replied were invited to Fleet Street to take a crossword test. Five of them completed the crossword within the allotted time, and another had only one word missing when the 12 minutes had expired. A few weeks later, all six were interviewed by military intelligence and recruited as codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

Kidnapping Codebooks

So far in this chapter, the Enigma traffic has been treated as one giant communications system, but in fact there were several distinct networks. The German Army in North Africa, for instance, had its own separate network, and their Enigma operators had codebooks that were different from those used in Europe. Hence, if Bletchley succeeded in identifying the North African day key, it would be able to decipher all the German messages sent from North Africa that day, but the North African day key would be of no use in cracking the messages being transmitted in Europe. Similarly, the Luftwaffe had its own communications network, and so in order to decipher all Luftwaffe traffic, Bletchley would have to unravel the Luftwaffe day key.

Some networks were harder to break into than others. The Kriegsmarine network was the hardest of all, because the German Navy operated a more sophisticated version of the Enigma machine. For example, the Naval Enigma operators had a choice of eight scramblers, not just five, which meant that there were almost six times as many scrambler arrangements, and therefore almost six times as many keys for Bletchley to check. The other difference in the Naval Enigma concerned the reflector, which was responsible for sending the electrical signal back through the scramblers. In the standard Enigma the reflector was always fixed in one particular orientation, but in the Naval Enigma the reflector could be fixed in any one of 26 orientations. Hence the number of possible keys was further increased by a factor of 26.

Cryptanalysis of the Naval Enigma was made even harder by the Naval operators, who were careful not to send stereotypical messages, thus depriving Bletchley of cribs. Furthermore, the Kriegsmarine also instituted a more secure system for selecting and transmitting message keys. Extra scramblers, a variable reflector, nonstereotypical messages and a new system for exchanging message keys all contributed to making German Naval communications impenetrable.

Bletchley’s failure to crack the Naval Enigma meant that the Kriegsmarine were steadily gaining the upper hand in the Battle of the Atlantic. Admiral Karl Dönitz had developed a highly effective two-stage strategy for naval warfare, which began with his U-boats spreading out and scouring the Atlantic in search of Allied convoys. As soon as one of them spotted a target, it would initiate the next stage of the strategy by calling the other U-boats to the scene. The attack would commence only when a large pack of U-boats had been assembled. For this strategy of coordinated attack to succeed, it was essential that the Kriegsmarine had access to secure communication. The Naval Enigma provided such communication, and the U-boat attacks had a devastating impact on the Allied shipping that was supplying Britain with much-needed food and armaments.

As long as U-boat communications remained secure, the Allies had no idea of the locations of the U-boats, and could not plan safe routes for the convoys. It seemed as if the Admiralty’s only strategy for pinpointing the location of U-boats was by looking at the sites of sunken British ships. Between June 1940 and June 1941 the Allies lost an average of 50 ships each month, and they were in danger of not being able to build new ships quickly enough to replace them. Besides the intolerable destruction of ships, there was also a terrible human cost-50,000 Allied seamen died during the war. Unless these losses could be drastically reduced, Britain was in danger of losing the Battle of the Atlantic, which would have meant losing the war. Churchill would later write, “Amid the torrent of violent events one anxiety reigned supreme. Battles might be won or lost, enterprises might succeed or miscarry, territories might be gained or quitted, but dominating all our power to carry on war, or even keep ourselves alive, lay our mastery of the ocean routes and the free approach and entry to our ports.”