The Conquering Tide (32 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

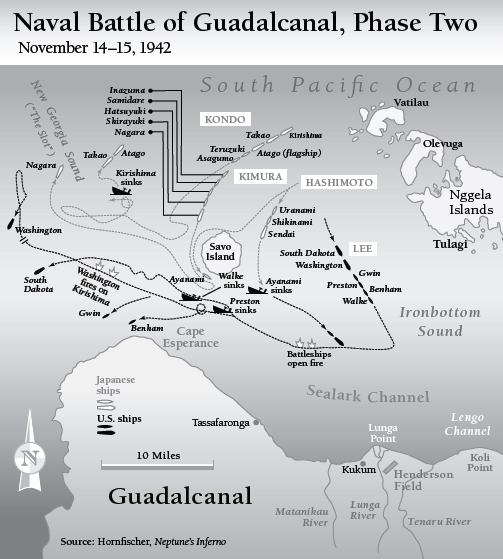

At about the same time, the

Benham

was struck by a torpedo on her starboard side. The foundering destroyer executed a sluggish starboard turn and limped away from the action. The

Walke

soldiered on, pumping 5-inch rounds at enemy ships off the south coast of Savo, until she was silenced by a series of heavy shells fired by an unidentified cruiser. Violent explosions blew slabs of her superstructure into the sea and set fires raging along her length. Her ready 20mm ammunition began “cooking off,” and her deck began to buckle. Captain Thomas E. Fraser ordered the men to abandon ship as she began to go down by the head. She sank at 12:42 a.m. Her depth charges had been set to safe, but a few apparently detonated as the ship went down, injuring or killing several of her surviving crew.

The

Gwyn

took a heavy salvo in her engine room. As her damage-control

parties struggled to save the ship, her captain ordered an emergency starboard turn to avoid the sinking remains of the

Preston

. She took more shell hits as she limped out of the battle.

The

Washington

's spotters, blinded by their ship's 16-inch muzzle flashes, lost visual contact with the enemy. Like their counterparts in the destroyers, they found the enemy by scanning the horizon for

his

muzzle flashes, and targeted them in return. The Japanese ships seemed to retreat beyond the black conical silhouette of Savo Island, perhaps fleeing the catastrophic punishment inflicted by the

Washington

's 16-inch shells.

A brief lull in the action followed as repair crews scrambled to correct electrical failures apparently caused by the concussion of the

Washington

's own guns, and her spotters scanned in vain for suitable targets. Where were the Japanese battleships?

The

Washington

increased speed to 26 knots and turned onto a course of 282 degrees. Her radar identified four large enemy ships coming into range south of Savo. While the

Washington

passed through and around the wreckage of the several crippled destroyers of the American van, her crew dropped life rafts over the side. The destroyers were in no condition to continue the fight, and the officer in tactical command ordered them to withdraw toward Guadalcanal as best they could.

South Dakota

surged ahead at 26 knots on a course of 290 degrees, firing on targets off Savo at a range of about 14,000 yards. The blast force of her tremendous weapons set her own floatplanes on fire and then blew them off their catapults and over the side. Circuit breakers tripped and power was cut to much of the ship. At about 12:45, steering clear of the sinking remains of the van destroyers, the

South Dakota

drew up on the

Washington

's starboard quarter.

The two battleships, without screening vessels, continued to the northwest. But the

South Dakota

diverged onto a more northerly course, which took her into illumination range of Japanese searchlights. That was a tactical blunder, as it would render moot the American advantage in fire control radar. The

Washington

's main battery fired on the battleship

Kirishima

, the first ship in the enemy line. The

Kirishima

returned fire, and the two behemoths dueled for the next several minutes at what amounted to close range for guns of that caliber.

The superstructure of the

South Dakota

, illuminated by searchlights, was

pounded by shells of many different calibers. The salvos destroyed much of her radar and communications equipment. She was unable to hail the flagship or even to see her. She was taking on water. Her turret 3 was inoperable, her fire control systems were seriously impaired, and she was leaking fuel.

70

A sailor recalled that “her decks were stacked high with dead, and sharp jagged edges from ripped steel were everywhere.”

71

All the Japanese guns fell silent at about 1:10 a.m., and the ships that could still make way began withdrawing to the northwest in apparent disorder. The

Washington

continued to pound away at the

Kirishima

and her screening vessels as they retired. Admiral Lee gave chase for the next

twenty minutes, and his ship continued to land shells on the enemy. But he was wary of a torpedo attack, and at 1:33 a.m., he decided to turn south. Dodging the odd torpedo track (launched by the retiring Japanese ships or perhaps even American PT boats), the

Washington

made radar contact with the

South Dakota

and the surviving American destroyers. Lee coaxed them in via TBS. At 6:49 a.m., after dawn, Lee received a radio dispatch from Halsey ordering him to pull his wounded ships together and bring them back to Espiritu Santo.

Lee had routed the enemy. The Japanese had brought a stronger force into the action, but it had been taken by surprise and been beaten by superior gunnery. The American advantage in radar fire control systems was readily evident; the Japanese systems were at least a year behind. Six Japanese ships were lost, including the

Kirishima

, which sank at 3:25 a.m. Five more were damaged. The survivors were in full retreat. The

Washington

had come through the action without significant damage. The

South Dakota

had been roughly handled but would be repaired and returned to service. The American destroyers had been decimatedâthree of four sunk, with heavy loss of lifeâbut they had played an essential part in the action by absorbing much of the enemy's punishment, both gunfire and torpedoes, allowing the battleships to concentrate their guns on the larger Japanese ships. Henderson Field was spared another shelling, and Tanaka's four surviving transports would be obliged to attempt a landing without naval protection.

T

ANAKA JUDGED THAT HIS ONLY HOPE

of unloading the four ships was to run them aground near Tassafaronga Point. He asked for permission to do so and received an affirmative reply from Rabaul. As November 15 dawned, the Americans could plainly see the four hulls propped up on the beaches to the west. About 2,000 troops got ashore before daylight, and stacks of crates and rice bales were left in and among the palm groves just inland of the beach.

72

Henderson-based planes worked over the ships and supplies throughout the morning. Except for brief and largely ineffective resistance by a few floatplane Zeros, the Japanese had no air protection. A marine 155mm artillery piece even managed to reach the nearest of the four ships, beached near the mouth of the Poha River. By midmorning all four ships were burning fiercely, and by early afternoon they were little more than charred husks emitting columns of greasy black smoke.

TBFs flying from Henderson targeted the supplies on the beach with the incendiary weapons nicknamed “Molotov bread baskets.”

73

A Dauntless pilot detected a trail leading from the beach inland to a circular clearing. Guessing it was an ammunition dump, he aimed his 1,000-pound bomb in the middle of that clearing. He had guessed right. A titanic explosion turned the heads of marines at Lunga, several miles away, and a column of smoke reached up to a height of 2,000 feet. The fire burned all night and was still burning sixteen hours later.

74

I

N THE THREE-DAY STRUGGLE KNOWN TO HISTORY AS THE

“Naval Battle of Guadalcanal,” the Japanese navy had been soundly defeated and driven back up the Slot. But Admiral Tanaka's beleaguered “Tokyo Express,” relying on fast destroyers darting into Ironbottom Sound under cover of darkness, had achieved the signal feat of putting more than a division of fresh troops ashore on the island. Added to the remnants of the Kawaguchi Corps, Japanese troop strength on Guadalcanal reached approximately 30,000 in mid-November. The Imperial General Headquarters had not anticipated that so many “sons of heaven” could fail to overrun the American position, but every successive assault on Vandegrift's lines had been bloodily repulsed. Now the immediate problem was logistics. It was becoming terribly clear that the Imperial Japanese Navy, having strained its capabilities to put so many troops ashore, had no practical means of feeding so many mouths. Even as early as September, Japanese units on the island had begun to waste away for lack of provisions, medicine, and other supplies. By the first week of December, they were succumbing en masse to plague and famine. Guadalcanal, for its Japanese inhabitants, had become “Starvation Island.”

*

Newcomers who came ashore at Tassafaronga Point were taken aback. Wraithlike soldiers approached and begged for food. Their uniforms, little more than rags, hung from emaciated limbs; their hair had grown long and crawled with lice; their skin was dirty and pocked with open sores that were

fed on by flies.

1

Many had thrown away their rifles because they either felt too weak to carry them or had no ammunition.

But the Japanese stationed along the coast were among the most prosperous on the island. There they could fish or forage for coconuts or plunder the meager supplies of rice brought ashore from the destroyers. Units posted deeper in the jungle had been reduced to eating lizards, snakes, worms, roots, grass, and insects. Trails into the hills were littered with the bodies of dead or dying men. Those immobilized by malaria, dengue fever, or beriberi were often abandoned to die where they lay. As one officer observed, food was the overriding obsession of starving men: “All senses, except hunger, went out. No laugh, no anger, no tear.”

2

Japanese soldiers' diaries, captured during and after the Guadalcanal campaign, told a pathetic story of deteriorating morale and wasted hopes. The malnourished soldiers were repeatedly exhorted to stir themselves to greater efforts: “We must by the most furious, daring, swift and positive action deal the enemy annihilating blows, [and] foil his plans completely. . . . It is necessary to arouse the officers and men to a fighting rage.”

3

But the officers made too many promises they could not keep. A fleet of Japanese transports, laden with food and other supplies, was always just over the western horizon; Japanese warplanes would soon darken the sky; one more

banzai

charge would cause the cowardly marines to throw away their weapons and run for their lives. But for days or even weeks at a time, no Japanese aircraft appeared overhead and no Japanese ships were seen offshore. “Every day enemy planes alone dance in the sky, fly low, strafe, bomb, and numerous officers and men fall,” noted a diarist on December 23. Three days later, he added, “O friendly planes! I beg that you come over soon, and cheer us up!”

4

Discipline collapsed. Soldiers bickered over their paltry rations. Food was stolen and hoarded. Enlisted men accused their officers of diverting extra portions to themselves. They refused to work, fight, or march unless fed. From the summit of Mount Austen, where a detachment of about 450 Japanese troops kept watch over Henderson Field, the lookouts watched miserably as American cargo ships anchored off Lunga Point and delivered a seemingly limitless quantity of supplies, weapons, and fresh troops into the American lines. A sub-lieutenant posted at the top of Austen devised a mortality table to predict each starving soldier's remaining life span:

Those who can stand upright: 30 days.

Those who can sit: 3 weeks.

Those always lying down: 1 week.

Those who pass urine lying: 3 days.

Those who cannot speak: 2 days.

Those who cannot wink: On the morrow.

5

On December 8, the Seventeenth Army headquarters on Guadalcanal reported that only 4,200 troops (about 15 percent of the total on the island) were strong and healthy enough to fight. Combat deaths were running at forty to fifty per day, mainly as a result of air attacks, but some three times that number were succumbing to disease or starvation.

6

Tanaka's mid-November resupply effort had been a debacle. He had lost eleven valuable transports in three days. From the four ships he had sacrificed by running them aground on the beaches, he had disembarked just 2,000 troops, 360 cases of ammunition for field guns, and 1,500 bales of rice.

7

By consuming so many scarce cargo ships, the fight for Guadalcanal threatened to cripple the entire Japanese war economy, which could not function without raw materials imported into the home islands.

A new supply tactic was urgently needed. Tanaka's hard-run destroyers would again be deployed as transports, this time using the “drum method.” Empty fuel drums were sterilized and filled with ammunition and provisions. The drums, linked together by ropes, were secured to the outboard railings of the destroyers. A column of destroyers would approach the island at high speed and cast away the drums, which would be retrieved by small craft (or even swimmers) and towed or hauled ashore. All supply drops would be attempted at night, as Tanaka dared not expose his ships to air attack.

The first run was attempted on November 30, 1942. Shortly after ten that evening, a single column of eight destroyers roared into Ironbottom Sound at nearly 30 knots. Admiral Tanaka knew that his ships had been spotted from the air, but hoped to launch the drums and withdraw up the Slot before daybreak. The weather was fair, with a gentle breeze and good visibility at the surface. Six of the eight ships were loaded with between 200 and 240 supply drums each. To offset the added weight topside, those six ships had sailed with only eight torpedoes (one per tube) and half their usual supply of main battery ammunition.

8