the Emigrants (6 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald

from happiness to misfortune, and was so terribly thin that he seems almost to have reached a physical vanishing point. Mme Landau could not tell me exactly what became of Helen Hollaender. Paul had preserved a resolute silence on the subject, possibly because he was plagued by a sense of having failed her or let her down. As far as Mme Landau had been able to discover, there could be little doubt that Helen and her mother had been deported, in one of those special trains that left Vienna at dawn, probably to Theresienstadt in the first instance.

Gradually, Paul Bereyter's life began to emerge from the background. Mme Landau was not in the least surprised that I was unaware, despite the fact that I came from S and knew what the town was like, that old Bereyter was what was termed half Jewish, and Paul, in consequence, only three quarters an Aryan. Do you know, she said on one of my visits to Yverdon, the systematic thoroughness with which these people kept silent in the years after the war, kept their secrets, and even, I sometimes think, really did forget, is nothing more than the other side of the perfidious way in which Schòferle, who ran a coffee house in S, informed Paul's mother Thekla, who had been on stage for some time in Nuremberg, that the presence of a lady who was married to a half Jew might be embarrassing to his respectable clientele, and begged to request her, with respect of course, not to take her afternoon coffee at his house any more. I do not find it surprising, said Mme Landau, not in the slightest, that you were unaware of the meanness and treachery that a family like the Bereyters were exposed to in a miserable hole such as S then was, and such as it still is despite all the so-called progress; it does not surprise me at all, since that is inherent in the logic of the whole wretched sequence of events.

In an effort to resume a more factual tone after the little outburst she had permitted herself, Mme Landau told me that Paul's father, a man of refinement and inclined to melancholy, came from Gunzenhausen in Franconia, where Paul's grandfather Amschel Bereyter had a junk shop and had married his Christian maid, who had grown very fond of him after a few years of service in his house. At that time Amschel was already past fifty, while Rosina was still in her mid twenties. Their marriage, which was naturally a rather quiet one, produced only one child, Theodor, the father of Paul. After an apprenticeship in Augsburg as a salesman, Theodor was employed for a lengthy spell in a Nuremberg department store, working his way up to the higher echelons, before moving to S in 1900 to open an emporium with capital saved partly from his earnings and partly borrowed. He sold everything in the emporium, from coffee to collar studs, camisoles to cuckoo clocks, candied sugar to collapsible top hats. Paul once described that wonderful emporium to her in detail, said Mme Landau, when he was in hospital in Berne in 1975, his eyes bandaged after an operation for cataracts. He said that he could see things then with the greatest clarity, as one sees them in dreams, things he had not thought he still had within him. In his childhood, everything in the emporium seemed far too high up for him, doubtless because he himself was small, but also because the shelves reached all the four metres up to the ceiling. The light in the emporium, coming through the small transom windows let into the tops of the display window backboards, was dim even on the brightest of days, and it must have seemed all the murkier to him as a child, Paul had said, as he moved on his tricycle, mostly on the lowest level, through the ravines between tables, boxes and counters, amidst a variety of smells - mothballs and lily-of-the-valley soap were always the most pungent, while felted wool and loden cloth assailed the nose only in wet weather, herrings and linseed oil in hot. For hours on end, Paul had said, deeply moved by his own memories, he had ridden in those days past the dark rows of bolts of material, the gleaming leather boots, the preserve jars, the galvanized watering cans, the whip stand, and the case that had seemed especially magical to him, in which rolls of Giitermann's sewing thread were neatly arrayed behind little glass windows, in every colour of the rainbow. The emporium staff consisted of Frommknecht, the clerk and accountant, one of whose shoulders was permanently raised higher from years of bending over correspondence and the endless figures and calculations; old Fraulein Steinbeiss, who flitted about all day long with a cloth and a feather duster; and the two attendants, Hermann Muller and Heinrich Miiller (no relation, as they incessantly insisted), who stood on either side of the monumental cash register, invariably wearing waistcoats and sleeve bands, and treated customers with the condescension that comes naturally, as it were, to those who occupy a higher station in life. Paul's father Theo Bereyter, though, whenever he, the emporium proprietor himself, came down to the shop for an hour or so (as he did every day) in his frock coat or a pin-striped suit and spats, would take up a position between the two potted palms, which would be either inside or outside the swing door depending on the weather, and would escort every single customer into the emporium with the most respectful courtesy, regardless of whether it was the neediest resident from the old people's home across the road or the opulent wife of Hastreiter, the brewery owner, and then see them out again with his compliments.

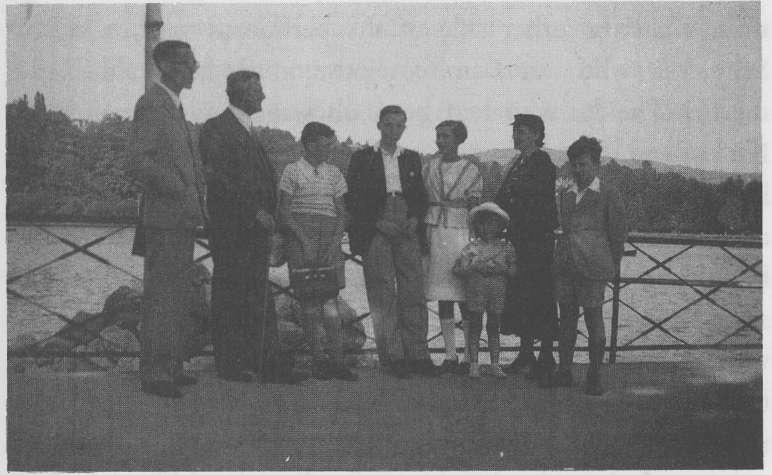

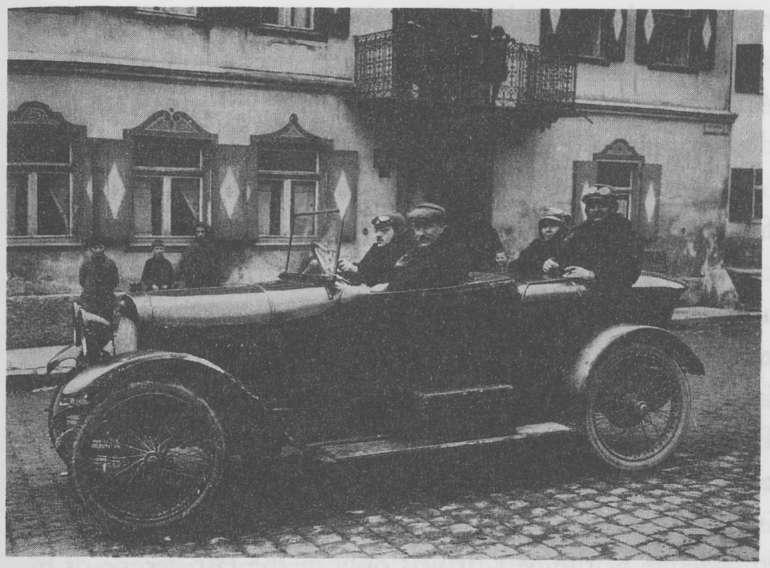

The emporium, Mme Landau added, being the only large store in the town and indeed in the entire district, by all accounts ensured a good middle class standard of living for the Bereyter family, and even one or two extravagances, as is evident (said Mme Landau) from the mere fact that Theodor drove a Diirkopp in the Twenties, attracting excited interest

as far afield as the Tyrol, Ulm or Lake Constance, as Paul liked to recall. Theodor Bereyter died on Palm Sunday, 1936; this too I heard from Mme Landau, who must have talked endlessly to Paul about these things, as I came to realize more clearly with every visit. The cause of death was given as heart failure, but in fact, as Mme Landau emphasized, he had died from the fury and fear that had been consuming him ever since, precisely two years before his death, the Jewish families, resident in his home town of Gunzenhausen for generations, had been the target of violent attacks. The emporium owner, escorted only by his wife and those in his employ, was buried before Easter in a remote corner, reserved for suicides and people of no denomination, behind a low wall in the churchyard at S. It is worth mentioning in this connection, said Mme Landau, that although the emporium, which passed to the widow, Thekla, could not be "Aryanized" after Theodor Bereyter's death, the family nonetheless had to sell it for next to nothing to Alfons Kienzle, a livestock and real estate agent who had recently set up as a respectable businessman. After this dubious transaction Thekla Bereyter fell into a depression and died within a few weeks.

All of these occurrences, Mme Landau said, Paul followed from afar without being able to intervene. On the one hand, when the bad news reached him it was always already too late to do anything, and, on the other, his powers of decision had been in some way impaired, making it impossible for him to think even as far as a single day ahead. For this reason, Mme Landau explained, Paul for a long time had only a partial grasp of what had happened in S in 1935 and 1936, and did not care to correct his patchy knowledge of the past. It was only in the last decade of his life, which he largely spent in Yverdon, that reconstructing those events became important to him, indeed vital, said Mme Landau. Although he was losing his sight, he spent many days in archives, making endless notes - on the events in Gunzenhausen, for instance, on that Palm Sunday of 1934, years before what became known as the Kristallnacht, when the windows of Jewish homes were smashed and the Jews themselves were hauled out of their hiding places in cellars and dragged through the streets. What horrified Paul was not only the coarse offences and the violence of those Palm Sunday incidents in Gunzenhausen, not only the death of seventy-five-year-old Ahron Rosenfeld, who was stabbed, or of thirty-year-old Siegfried Rosenau, who was hanged from a railing; it was not only these things, said Mme Landau, that horrified Paul, but also, nearly as deeply, a newspaper article he came across, reporting with

Schadenfreude

that the schoolchildren of Gunzenhausen had helped themselves to a free bazaar in the town the following morning, taking several weeks' supply of hair slides, chocolate cigarettes, coloured pencils, fizz, powder and many other things from the wrecked shops.

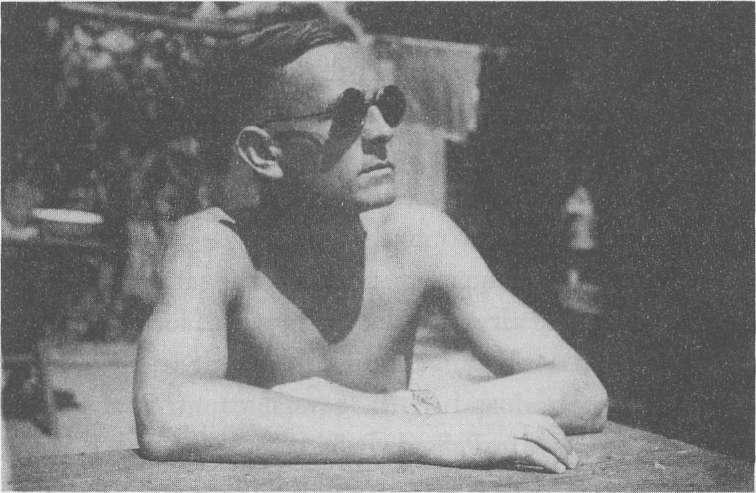

What I was least able to understand in Paul's story, after all that, was the fact that in early 1939 - be it because the position of a German tutor in France in times that were growing more difficult was no longer tenable, or out of blind rage or even a sort of perversion - he went back to Germany, to the capital of the Reich, to Berlin, a city with which he was quite unfamiliar. There he took an office job at a garage in Oranienburg, and a few months later he was called up; those who were only three-quarter Aryans were apparently included in the muster. He served, if that is the word, for six years, in the motorized artillery, variously stationed in the Greater German homeland and in the several countries that were occupied. He was in Poland, Belgium, France, the Balkans, Russia and the Mediterranean, and doubtless saw more than

any heart or eye can bear. The seasons and the years came and went. A Walloon autumn was followed by an unending white winter near Berdichev, spring in the Departement Haute-Saóne, summer on the coast of Dalmatia or in Romania, and always, as Paul wrote under this photograph,

one was, as the crow flies, about 2,000 km away - but from where? - and day by day, hour by hour, with every beat of the pulse, one lost more and more of one's qualities, became less comprehensible to oneself, increasingly abstract.

Paul's return to Germany in 1939 was an aberration, said Mme Landau, as was his return to S after the war, and to his teaching life in a place where he had been shown the door. Of course, she added, I understand why he was drawn back to school. He was quite simply born to teach children - a veritable Melammed, who could start from nothing and hold the most inspiring of lessons, as you yourself have described to me. And furthermore, as a good teacher he would have believed that one could consider those twelve wretched years over and done with, and simply turn the page and begin afresh. But that is no more than half the explanation, at most. What moved and perhaps even forced Paul to return, in 1939 and in 1945, was the fact that he was a German to the marrow, profoundly attached to his native land in the foothills of the Alps, and even to that miserable place S as well, which in fact he loathed and, deep within himself, of that I am quite sure, said Mme Landau, would have been pleased to see destroyed and obliterated, together with the townspeople, whom he found so utterly repugnant. Paul, said Mme Landau, could not abide the new flat that he was more or less forced to move into shortly before he retired, when the wonderful old Lerchenmiiller house was pulled down to make way for a hideous block of flats; but even so, remarkably, in all of those last twelve years that he was living here in Yverdon he could never bring himself to give up that flat. Quite the contrary, in fact: he would make a special journey to S several times a year especially to see that all was in order, as he put it. Whenever he returned from one of those expeditions, which generally took just two days, he would always be in the gloomiest of spirits, and in his childishly appealing way he would rue the fact that, to his own detriment, he had once again ignored my urgent advice not to go there any more.