the Emigrants (8 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald

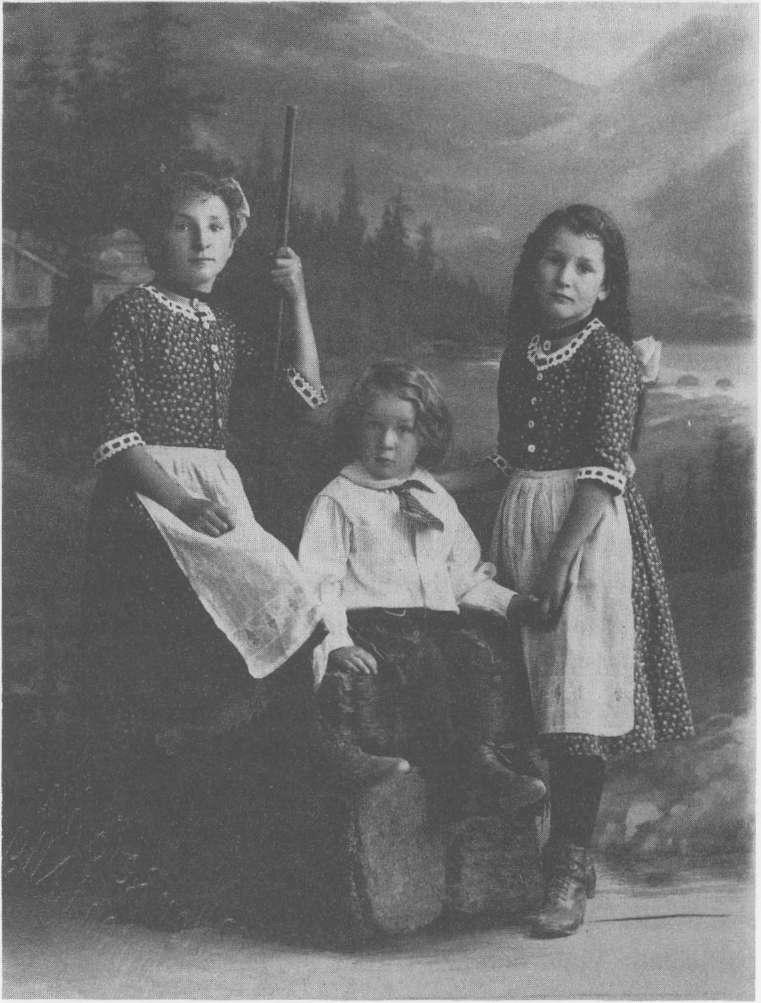

Our relatives' summer visits were probably the initial reason why I imagined, as I grew up, that I too would one day go to live in America. More important, though, to my dream of America was the different kind of everyday life displayed by the occupying forces stationed in our town. The local people found their moral conduct in general - to judge by comments sometimes whispered, sometimes spoken out loud - unbecoming in a victorious nation. They let the houses they had requisitioned go to ruin, put no window boxes on the balconies, and had wire-mesh fly screens in the windows instead of curtains. The womenfolk went about in trousers and dropped their lipstick-stained cigarette butts in the street, the men put their feet up on the table, the children left their bikes out in the garden overnight, and as for those negroes, no one knew what to make of them. It was precisely this kind of disparaging remark that strengthened my desire to see the one foreign country of which I had any idea at all. In the evenings, but particularly during the endless lessons at school, I pictured every detail of my future in America. This period of my imaginary Americanization, during which I crisscrossed the entire United States, now on horseback, now in a dark brown Oldsmobile, peaked between my sixteenth and seventeenth years in my attempt to perfect the mental and physical attitudes of a Hemingway hero, a venture in mimicry that was doomed to failure for various reasons that can easily be imagined. Subsequently my American dreams gradually faded away, and once they had reached vanishing point they were presently supplanted by an aversion to all things American. This aversion became so deeply rooted in me during my years as a student that soon nothing could have seemed more absurd to me than the idea that I might ever travel to America except under compulsion. Even so, I did eventually fly to Newark on the 2nd of January 1981. This change of heart was prompted by a photograph album of my mother's which had come into my hands a few months earlier and which contained pictures quite new to me of our relatives who had emigrated during the Weimar years. The longer I studied the photographs, the more urgently I sensed a growing need to learn more about the lives of the people in them. The photograph that follows here, for example, was taken in the Bronx

in March 1939. Lina is sitting on the far left, next to Kasimir. On the far right is Aunt Theres. I do not know who the other people on the sofa are, except for the little girl wearing glasses. That's Flossie, who later became a secretary in Tucson, Arizona, and learnt to belly dance when she was in her fifties. The oil painting on the wall shows our village of W. As far as I have been able to discover, no one now knows the whereabouts of that picture. Not even Uncle Kasimir, who brought it with him to New York rolled up in a cardboard tube, as a farewell gift from his parents, knows where it can have got to.

So on that 2nd of January, a dark and dreary day, I drove south from Newark airport on the New Jersey turnpike in the direction of Lakehurst, where Aunt Fini and Uncle Kasimir, after they moved away from the Bronx and Mamaroneck in the mid Seventies, had each bought a bungalow in a so-called retirement community amidst the blueberry fields. Right outside the airport perimeter I came within an inch of driving off the road when a Jumbo rose ponderously into the air above a truly mountainous heap of garbage, like some creature from prehistoric times. It was trailing a greyish black veil of vapour, and for a moment it was as if it had spread its wings. Then I drove on into flat country, where for the entire length of the Garden State Parkway there was nothing but stunted trees, fields overgrown with heather, and deserted wooden houses, partly boarded up, with tumble-down cabins and chicken runs all around. There, Uncle Kasimir told me later, millions of hens were kept up to the postwar years, laying millions upon millions of eggs for the New York market till new methods of poultry-keeping made the business unprofitable and the smallholders and their birds disappeared. Shortly after nightfall, taking a side road that ran off from the Parkway for several kilometres through a kind of marshland, I reached the old peoples' town called Cedar Glen West. Despite the immense territory covered by this community, and despite the fact that the bungalow condominiums were indistinguishable from each other, and, furthermore, that almost identical glowing Father Christ-mases were standing in every front garden, I found Aunt Finis house without difficulty, since everything at Cedar Glen West is laid out in a strictly geometrical pattern.

Aunt Fini had made

Maultaschen

for me. She sat at the table with me and urged me to help myself whilst she ate nothing, as old women often do when they cook for a younger relative who has come to visit. My aunt spoke about the past, sometimes covering the left side of her face, where she had had a bad neuralgia for weeks, with one hand. From time to time she would dry the tears that pain or her memories brought to her eyes. She told me of Theo's untimely death, and the years that followed, when she often had to work sixteen hours or more a day, and went on to tell me about Aunt Theres, and how, before she died, she had walked around for months as if she were a stranger to the place. At times, in the summer light, she had looked like a saint, in her white twill gloves which she had worn for years on account of her eczema. Perhaps, said Aunt Fini, Theres really was a saint. At all events she shouldered her share of troubles. Even as a schoolchild she was told by the catechist that she was a tearful sort, and come to think of it, said Aunt Fini, Theres really did seem to be crying most of her life. She had never known her without a wet handkerchief in her hand. And, of course, she was always giving everything away: all she earned, and whatever came her way as the keeper of the millionaire Wallerstein's household. As true as I'm sitting here, said Aunt Fini, Theres died a poor woman. Kasimir, and particularly Lina, doubted it, but the fact was that she left nothing but her collection of almost a hundred Hummel figurines, her wardrobe (which was splendid, mind you) and large quantities of paste jewellery - just enough, all told, to cover the cost of the funeral.

Theres, Kasimir and I, said Aunt Fini as we leafed through her photo album, emigrated from W at the end of

the Twenties. First, I took ship with Theres at Bremerhaven on the 6th of September 1927. Theres was twenty-three and I was twenty-one, and both of us were wearing bonnets. Kasimir followed from Hamburg in summer 1929, a few weeks before Black Friday. He had trained as a tinsmith, and was just as unable to find work as I was, as a teacher, or Theres, as a sempstress. I had graduated from the Institute at Wettenhausen the previous year, and from autumn 1926 I had worked as an unpaid teaching assistant at the primary school in W. This is a photograph taken at that time. "We were on an outing to Falkenstein. The pupils all stood in the back of the

lorry, while I sat in the driver's cab with a teacher named Fuchsluger, who was one of the very first National Socialists, and Benedikt Tannheimer, who was the landlord of the Adler and the owner of the lorry. The child right at the back, with a cross marked over her head, is your mother, Rosa. I remember, said Aunt Fini, that a month or so later, two days before I embarked, I went to Klosterwald with her, and saw her to her boarding school. At that time, I think, Rosa had a great deal of anxiety to contend with, given that her leaving home coincided so unhappily with her siblings' departure for another life overseas, for at Christmas she wrote a letter to us in New York in which she said she felt fearful when she lay awake in the dormitory at night. I tried to console her by saying she still had Kasimir, but then Kasimir left for America too, when Rosa was just fifteen. That's the way it always is, said Aunt Fini thoughtfully: one thing after another. Theres and I, at any rate, she continued after a while, had a comparatively easy time of it when we arrived in New York. Uncle Adelwarth, a brother of our mother, who had gone to America before the First World War and had been employed only in the best of houses since then, was able to find us positions immediately, thanks to his many connections. I became a governess with the Seligmans in Port Washington, and Theres a lady's maid to Mrs Wallerstein, who was about the same age and whose husband, who came from somewhere near Ulm, had made a considerable fortune with a number of brewing patents, a fortune that went on growing as the years went by.

Uncle Adelwarth, whom you probably do not remember any more, said Aunt Fini, as if a quite new and altogether more significant story were now beginning, was a man of rare distinction. He was born at Gopprechts near Kempten in 1886, the youngest of eight children, all of them girls except for him. His mother died, probably of exhaustion, when Uncle Adelwarth, who was given the name Ambros, was not yet two years old. After her death, the eldest daughter, Kreszenz, who cannot have been more than seventeen at the time, had to run the household and play the role of mother as best she could, while their father the innkeeper sat with his customers, which was all he knew how to do. Like the other siblings, Ambros had to give Zenzi a hand quite early on, and at five he was already being sent to the weekly market at Immenstadt, together with Minnie, who was not much older, to sell the chanterelles and cranberries they had gathered the day before. Well into the autumn, said Aunt Fini, the two youngest of the Adelwarth children sometimes did nothing for weeks on end but bring home basketfuls of rosehips; they would cut them open, then dig out the hairy seeds with the tip of a spoon, and, after leaving them in a washtub for a few days to draw moisture, put the red flesh of the hips through the press. If one thinks now of the circumstances in which Ambros grew up, said Aunt Fini, one inevitably concludes that he never really had a childhood. When he was only thirteen he left home and went to Lindau, where he worked in the kitchens of the Bairischer Hof till he had enough for the rail fare to Lausanne, the beauties of which he had once heard enthusiastically praised at the inn in Gopprechts by a travelling watchmaker. Why, I shall never know, said Aunt Fini, but in my mind's eye I always see Ambros crossing Lake Constance from Lindau by steamer, in the moonlight, although that can scarcely have been how it was in reality. One thing is certain: that within a few days of leaving his homeland for good, Ambros, who was then fourteen at the outside, was working as an

apprenti garfon

in room service at the Grand Hotel Eden in Montreux, probably thanks to his unusually appealing but nonetheless self-controlled nature. At least I think it was the Eden, said Aunt Fini, because, in one of the postcard albums that Uncle Adelwarth left, the world-famous hotel is on one of the opening pages, with its awnings lowered over the windows against the afternoon sun. During his apprenticeship in Montreux, Aunt Fini continued, after she had fetched the album from one of her bedroom drawers and opened it up before me, Ambros wasl