The Essential Book of Fermentation (27 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

Bottling was fun—and hard work. Wine is poured into the top of a metal bottler that has five slender spigots. Bottles are placed so the spigot runs down into the neck of the bottle. The machine automatically stops filling when the wine reaches the proper level in the neck of the bottle. The bottles are then handed to the two guys running the corker. One guy—usually me—kept buckets of water full of corks so they’d be wet when inserted into the bottles. The other guy worked an Italian corking machine, a hand-operated gismo. I’d grab a bottle and put it onto the corker’s stand. Then I’d drop a cork into the top of the corker. The guy manning the corker would pull down a long lever and the cork would be squeezed by sliding metal chocks and then driven into the neck of the bottle. Then—to bottle 120 gallons of wine—the process would be repeated 599 more times. It took two or three hours to cork all the bottles. Then they’d be put into cases, turned on their sides so the corks would be in contact with the wine, and set aside. Of course, we’d be tasting our new wine as we worked, listening to the local rock station, taking a break and eating sandwiches the women would prepare (when we weren’t pressing them into service on the bottling line), and generally making a social event out of it.

Soon the new vintage would be under way, with the work that entailed. So it was not until the following April that we’d get to labeling and foiling the bottles. Our labels were handsome—black with silver embossing. These were applied using a labeling bench. The cases of wine were brought forth. Each unlabeled bottle—called a shiner in the argot of the trade—was laid horizontally between two blocks of wood that held it steady. A label was zipped through a machine with a roller that revolved into a vat of heated glue, so that glue was applied by the roller to the back of the label. They were then fixed to the bottle by hand, making sure they were all on straight and in the right place. Then they were handed to the foiler. He used a machine that looked like a vacuum cleaner tank with a hole in one end. A silver foil capsule was placed over the neck of the bottle and the neck was inserted into the foiler, which had revolving rubber rings that squeezed the capsule tightly onto the top of the neck. Again, it took good quantities of our own wine, which by this time was tasting very, very good, to encourage us to finish the work.

The bottles were then placed back in the cases and a label fixed to the end of each case so we could tell what was inside. At the end, we divvied up the cases. A hundred and twenty gallons—minus a gallon we drank during the bottling—comes to about six hundred bottles. At twelve bottles to a case, that’s about fifty cases—sometimes a little more, depending on how much juice is in the grapes, sometimes a little less. Ideally, each of the four guys gets twelve cases and the leftovers go into our little home winery’s “library,” to drink a bottle at a time, as the years go by, at our annual Talla Mena dinner. Talla Mena (named after a Finnish drinking game) is the name of our winery. Each year we take one bottle from each vintage from the library and sample them at our dinners. I think we’ve finally run out of the 1976—our first vintage, and a Cabernet Sauvignon that still tastes as good as the day it was made. No, wait a second. It tastes much better than the day it was made. That’s the thing about wine.

WINE AND HEALTH

The current federal dietary guidelines recommend no more than one five-ounce glass of wine daily for women and two glasses for men. Since a 750-ml bottle of wine contains about 25 ounces, that would be five five-ounce glasses. If one has a glass of wine or two with lunch or dinner on a daily basis, one is a moderate drinker, and the person to whom all the health benefits of moderate wine consumption accrue.

Studies show that moderate drinkers do enjoy more health benefits than either teetotalers or binge drinkers. In this regard, wine is very much like cheese, which has a high fat content. A moderate amount of either is fine. Too much of either can lead to serious health problems. But then, no wine or cheese at all is simply too depressing to think about. After all, as the French saying goes, “Nothing equals the joy of the drinker, except the joy of the wine in being drunk.” Even the Bible, 1 Timothy 5:23, tells us, “You should give up drinking only water and have a little wine for the sake of your digestion and the frequent bouts of illness that you have.” My personal opinion, gained from much experience with a glass of good wine and a plate of good food, is that the drink relaxes me after a day’s hard work, washes away care, soothes the work-jangled mind, and prompts mirth and good feeling. That, I believe, is the true source of wine’s beneficial effects on the human organism. It’s an opinion shared by many in the Society of Medical Friends of Wine, a physicians’ group in San Francisco that researches and discusses the health benefits of moderate wine consumption.

PART 3

The Recipes

Wer nicht liebt Wein, Weib und Gesang,

Der bleibt ein Narr sein Leben lang.

(Who does not love wine, women, and song,

Remains a fool his whole life long.)

—MARTIN LUTHER

CHAPTER 11

The Dairy Ferments

Making Milk Kefir

Kefir (properly pronounced

keh-FEER

rather than

KEE-fir

) is a tangy, milk-or water-based drink fermented by a symbiotic combination of bacteria and yeast clumped together in a matrix of proteins, fats, and sugar. It’s a wonderfully rich source of healthy, diverse microbes and will do you a world of good. Kefir originated in the North Caucasus region, but no one knows precisely where or when. It comes to us from the mists of time, most likely handed down through many hundreds of generations.

You can buy commercial kefir at the store, but you’ll make a better version at home. My local market sells raw, whole, organic milk from pastured cows, and believe me, that makes kefir that’s far better than the commercial product. However, regular milk—even fat-free milk—will make kefir. If you buy organic milk, you can be sure that it does not contain the residual antibiotics that are routinely used on cows in conventional dairies. Kefir microbes do not thrive in milk that contains antibiotics.

The symbiotic combination (or culture) of bacteria and yeast (the often used acronym is SCOBY) forms “grains” that resemble small cauliflower florets. Some scientific sources have found up to thirty different kinds of bacteria in the grains. The microbes in these grains proliferate in milk and will make a fresh batch of kefir— which is the fermented milk with the grains strained out—every twenty-four hours.

Kefir grains contain a water-soluble polysaccharide known as kefiran, which imparts a thick texture and smooth feeling in the mouth to the fermented milk. Kefiran ranges in color from white to yellow. The grains will grow over time, and can get to be the size of walnuts (although rice-size grains and sizes in between are most common). It’s this gorgeous texture that partly explains kefir’s exploding popularity. A store called Treat Petite in Manhattan was an early source for soft-serve frozen kefir, which isn’t as sweet as yogurt. Frozen kefir is now found online and in some retail stores.

Milk kefir has a tangy flavor and a silky texture. It’s rich, and it feels good just drinking it. You can add a splash of fruit juice to the kefir if you find the taste too cheesy, but many people prefer it plain because its taste fairly shouts the word “wholesome!” Its tangy flavor is versatile. It’s perfect with morning cereal instead of milk, and you can use it in salad dressings, to make ice cream, to thicken and improve soup, instead of milk in smoothies, and in baking pastries and breads.

Kefir’s microorganisms colonize the intestines and benefit health by protecting the intestine against disease-causing bacteria and by strengthening the diverse ecosystem of the gut, which also supports positive health. The kefiran in kefir has been shown in one study to suppress an increase in blood pressure and reduce blood cholesterol levels in rats. Kefir also contains compounds that show antimutagenic and antioxidant properties in laboratory tests, although it is not yet clear whether these results occur when kefir is drunk.

One noticeable way kefir will improve your health is to increase your regularity, lessen the need to strain at stools, and decrease any digestive problems you may have. Kefir reduces flatulence and is a wonder food for your intestinal flora. In fact, kefir microbes colonize your gut, especially the colon, and become part of your intestinal flora—part of you.

I bought a kit to make kefir from a seller on eBay for $26. The kit included a plastic bag of milk kefir grains and one of water kefir grains, a plastic strainer, and instructions for use. It has turned out to be one of the best $26 purchases I’ve ever made. All these tools and the grains, along with just about anything else needed to ferment or culture many kinds of food, can also be found for sale online at www .culturesforhealth.com. The eBay seller’s literature said that kefir grains should not come in contact with metal because of their acidity. The acidity can react with certain metals such as aluminum, and cause an electrical gradient on metal surfaces that can harm the microbes. Glass, plastic, or ceramic is okay. So here’s the equipment I use to make my daily kefir:

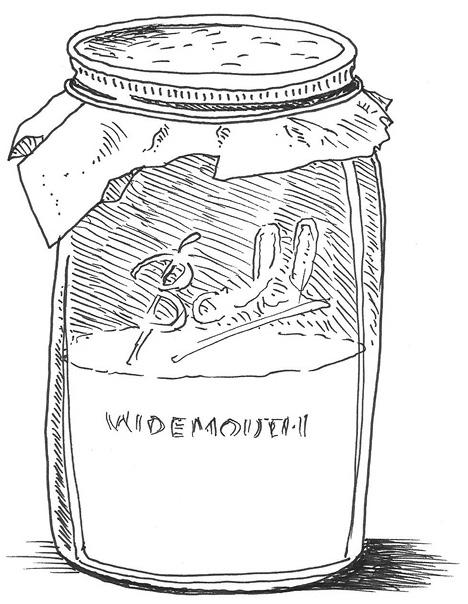

- A 1-quart wide-mouth canning jar

- A wide-mouth plastic funnel

- A plastic mesh strainer

- A ceramic bowl that is deep enough so the strainer doesn’t touch the bottom when it’s suspended on the bowl

- A plastic spoon

When I got my grains from the eBay supplier, both milk and water kefir grains were securely sealed in zip-top plastic bags. I put the water kefir grains in the fridge to prepare later (the recipe for water kefir starts

here

). Following his instructions, I placed the milk kefir grains as is (unwashed) in the quart canning jar, which I then filled halfway with a pint of raw whole milk. I decided to use raw whole milk for several reasons. The raw milk would have all of its natural enzymes intact, increasing its ability to convert lactose to lactic acid. I guessed that the microbes in the SCOBY would be happier in raw milk than pasteurized. And I went with whole milk simply because of its completeness as the product that came from the cow as nature intended. Then I remembered that J. I. Rodale—who introduced organic gardening and farming to the nation in 1942, when he created

Organic Farming and Gardening

magazine—used to say that cow’s milk is for calves, not human beings. But he was talking about milk, not kefir.

Cover the top with a piece of paper towel and screw it down with the metal band that comes with the canning lid.