The Everything Writing Poetry Book (20 page)

The sestina rotates the end words until they appear in each position in a stanza. In the envoi, since that stanza has only three lines, two of the end words will appear in each line. However, one of the end words appears in the middle of the line while the other appears at the end. Hence, in the first line of the envoi, for example, end word

B

will appear somewhere in the middle of the line, and end word

E

will appear at the end.

As an example of the sestina form, consider Algernon Charles Swinburne's “Sestina.” Using the chart here, follow through his poem to see how the end words appear and how he constructs his envoi.

/saw my soul at rest upon a day

As a bird sleeping in the nest of night,

Among soft leaves that give the starlight way

To touch its wings but not its eyes with light;

So that it knew as one in visions may,

And knew not as men waking, of delight

.

This was the measure of my soul's delight;

It had no power of joy to fly by day,

Nor part in the large lordship of the light;

But in a secret moon-beholden way

Had all its will of dreams and pleasant night,

And all the love and life that sleepers may

.

But such life's triumph as men waking may

It might not have to feed its faint delight

Between the stars by night and sun by day,

Shut up with green leaves and a little light;

Because its way was as a lost star's way,

A world's not wholly known of day or night

.

All loves and dreams and sounds and gleams of night

Made it all music that such minstrels may,

And all they had they gave it of delight;

But in the full face of the fire of day

What place shall be for any starry light,

What part of heaven in all the wide sun's way?

Yet the soul woke not, sleeping by the way,

Watched as a nursling of the large-eyed night,

And sought no strength nor knowledge of the day,

Nor closer touch conclusive of delight,

Nor mightier joy nor truer than dreamers may,

Nor more of song than they, nor more of light

.

For who sleeps once and sees the secret light

Whereby sleep shows the soul a fairer way

Between the rise and rest of day and night,

Shall care no more to fare as all men may,

But be his place of pain or of delight,

There shall he dwell, beholding night as day

.

Song, have thy day and take thy fill of light

Before the night be fallen across thy way;

Sing while he may, man hath no long delight

.

Swinburne has very ambitiously included a rhyme scheme for his end words, and he has brought each line into iambic pentameter. You, however, do not need to create a rhyme or keep to a meter. It is more important that the content of the poem seem natural rather than forced.

The Pantoum

The modern pantoum is based upon a Malayan form called the

pantun

that dates back to the fifteenth century. Like the villanelle and the sestina, the pantoum is not bound to a meter, but unlike the villanelle or the sestina, the pantoum does not have a length limit. It can be several stanzas long or only a couple, depending on your needs. As such, it makes an ideal poem for experimenting with closed forms in general and for practicing repeated verse.

The pantoum form is based on a few simple requirements. First, the entire poem is written in quatrains, the lines being of any reasonable length. Second, you may write with a rhyme scheme of ABAB, or you can avoid the rhyme altogether and work solely with the repetitions that are the basis of the form. Third, those repetitions follow an easy formula: The second and fourth lines (also called

refrains

) of one quatrain become the first and third lines of the following quatrain. Finally, the first and third lines of the opening quatrain are repeated in the final quatrain.

If you were writing a six-stanza pantoum, the scheme would look like this (remember that the letters indicate repeated lines, not rhymes): ABCD, BEDF, EGFH, GIHJ, IKJL, KCLA. Notice that in the closing quatrain, the lines that you repeat from the first stanza flip-flop in order. In other words, line three from the first stanza appears in the second line of the last stanza, while the opening line of the poem becomes the closing line. This graceful sequence makes the poem self-contained, with every line finding an echo somewhere later in the scheme. Several modern poets favor this form; some pantoums you might enjoy include Linda Pastan's “Something about the Trees,” Thomas Lux's “All the Slaves,” John Ashbery's “Pantoum,” and Carolyn Kizer's “Parents' Pantoum.”

Vive la Villanelle

As a poetic form, the villanelle passed from France to England sometime during the nineteenth century. American poets picked up the form soon after, and many well-known English-speaking poets have tried the form since. The villanelle is a short poemâonly nineteen linesâbut the form weaves repetition and rhyme in an intricate pattern. It is created out of three-lined stanzas called

tercets

and a four-lined quatrain. Here is the pattern for its rhyme and repetition: ABA, ABA (repeat line 1), ABA (repeat line 3), ABA (repeat line 1), ABA (repeat line 3), ABA (repeat line 1), A (repeat line 3). This pattern is easier to understand when considering an example.

You may notice that in many poems the first word of each line begins with a capital letter. This has been a poetic convention for centuriesâa device used to distinguish poetry from proseâbut you do not need to follow it. Poets like e.e. cummings have disregarded this convention and many other poetic principles in the past century.

If you feel the need, you may incorporate slant and eye rhymes, or make small changes to the repeated lines when they reappear, in order to add nuances to the poem. To give you an idea of how the villanelle form has been used by a professional poet, consider Edwin Arlington Robinson's “Villanelle of Change”:

Since Persia fell at Marathon,

The yellow years have gathered fast:

Long centuries have come and gone

.

And yet (they say) the place will don

A phantom fury of the past,

Since Persia fell at Marathon;

And as of old, when Helicon

1

Trembled and swayed with rapture vast

(Long centuries have come and gone)

,

This ancient plain, when night comes on,

Shakes to a ghostly battle-blast,

Since Persia fell at Marathon

.

But into soundless Acheron

2

The glory of Greek shame was cast:

Long centuries have come and gone

,

The suns of Hellas

3

have all shone,

The first has fallen to the last: â

Since Persia fell at Marathon,

Long centuries have come and gone

.

1

Mountain in Greece where the Muses, goddesses of the performing arts, would often gather

2

Underworld river

3

One of many names for the ancient Greeks

Variation One: The Terzanelle

There are two main variations of the villanelle form that you should be aware of. The first is the

terzanelle

. This form has the same number of lines and stanzas as the villanelle, but it uses a different pattern of repetition. As you will see, the middle line of one tercet is repeated as the refrain in the last line of the next tercet. The entire scheme for the poem looks like this: AB (refrain 1) A, BC (refrain 2) B (refrain 1), CD (refrain 3) C (refrain 2), DE (refrain 4) D (refrain 3), EF (refrain 5) E (refrain 4), FA (repeat line 1) F (refrain 5) A (repeat line 3). The last stanza of the terzanelle has an alternative scheme, FFAA, in which the first line continues the rhyme scheme started in the poem's fourteenth line, the second line repeats refrain 5, the third line repeats the first line of the poem, and the last line repeats the third line of the poem.

The terzanelle gets its name from the rhyme scheme called the

terza rima

, used in the tercets. As you can see from the scheme shown here, the terza rima involves an interlinking patternâthe middle line of one tercet rhymes with the first and last lines of the next tercet. This pattern gives you more resources for rhyming than the villanelle, which limits you to two rhymes. Fewer terzanelles than villanelles have been written, so examples are harder to find, but two that you might enjoy include “Terzanelle in Thunderweather” by Lewis Turco and “Terzanelle at Twilight” by Arpitha Raghunath.

The

terza rima

has a long and honorable history in Italian poetry. It is said that Dante Alighieri, who wrote

The Divine Comedy

, the master-piece of the Middle Ages, invented the rhyme and the stanza to honor the Trinity in his work.

Variation Two: The Triolet

The

triolet

, another French form, found its way into English poetry sometime in the seventeenth century. It is a simpler form than the villanelle, and as such may be a good way to warm up to the more difficult form. The triolet is only eight lines long and is built around the repetition of two lines and two rhymes. Here is the scheme of the form: A (refrain 1), B (refrain 2), A (rhymes with line 1), A (refrain 1), A (rhymes with lines 1 and 3), B (rhymes with line 2), A (refrain 1), B (refrain 2).

The trick to the triolet is to add enough meaning to the rhyming lines so that the refrains don't simply repeat what you have said before (the same could be said about the villanelle and the terzanelle). Also, keep in mind that as with the villanelle and the terzanelle, you are not limited by a meter. However, you can work with one if you prefer.

Build a Sestina

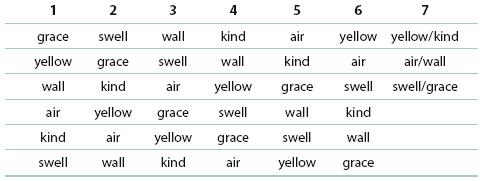

Due to the reliance of the sestina, the pantoum, and the villanelle on repeated words or lines, you can practice with the same exercises for all three forms. Getting used to the schemes that govern the repetitions must be your first step in mastering these forms. The first exercise will be to practice the repeating pattern of the sestina. Take six words and arrange them into the pattern called for by the form. Your arrangement might look something like this:

Repetition Exercise

Remember that the last stanza (the envoi), in the form of a tercet, has a pair of the repeated words in each lineâone in the middle of the line and one at the end. For example,

yellow

would come in the middle of the tercet's first line and

kind

at the end. In the tercet's second line,

air

would come somewhere in the middle and

wall

at the end. Starting with the list you created, you could write something like this for the first two stanzas:

In the end, it is only by the grace

of God that our souls don't turn yellow

or stumble like drunk monkeys into a wall.

Our words of supplication hold the air

still. If we speak louder, beg, a kind

of frozen chuckle, a swell

of the throat, chokes us. Oh, swell.

Our limbs, exhausted and grace-

less, offer no help. What kind

of gesture could we make anyway? Some yellow-

bellied genuflection, hands sweeping air,

eyes searching the paint on the wall?