The Everything Writing Poetry Book (21 page)

This draft has varied the line lengths but maintained the pattern of repeated words. Notice, too, how function and category shift occurs with the words

grace

(noun) and

graceless

(adjective), and

swell

(noun) and

swell

(interjection). Notice also that the end of each line does not necessarily mean the end of a sentence or clause. Once you have your own opening pair of stanzas, you can press onward if you feel inspired, or you can set them aside and wait for more ideas to come.

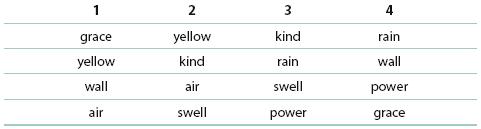

Build a Pantoum

The next exercise you can try is to take the list of end words you made for the sestina and rearrange the words into the pantoum pattern. You need to remember that the pantoum is built with quatrains rather than the six-lined stanzas used in the sestina, so the words will take up different positions. Some of the words may not make it into the list at all. Remember, too, that the words at the ends of lines one and three in the opening stanza will reappear in lines two and four in the closing stanza, in reverse order. For simplicity's sake, here is one with four stanzas:

Pantoum Exercise

For this exercise, take the word list that you just created and see if you can begin filling out the lines. Again, your lines don't have to conform to a meter or a rhyme scheme, though the lines shouldn't be so long that they take up the whole page. The exercise you generate might look like this:

In the end, it is only by the grace

of God that our souls don't turn yellow

or stumble like drunk monkeys into a wall.

Our words of supplication still the air

.

Our souls don't turn yellow

only because God is kind.

Our words of supplication still the air

or stop the ocean's swell

.

Only because God is kind

can we open our eyes, watch the rain,

or stop the ocean's swell.

That is the meaning of power

.

Will we open our eyes, watch the rain,

stumble like drunk monkeys into a wall?

That is the meaning of power.

In the end, we live only by God's grace

.

Your exercise may be rough and the word choice somewhat awkward, but don't be discouraged. The most important thing to look for is that, aside from a few small exceptions, the refrains repeat as they should throughout the poem. Remember to use enjambment to make some of the lines fit together more smoothly.

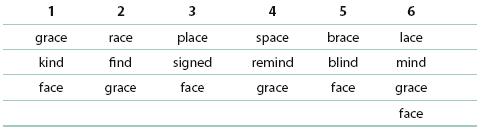

Build a Villanelle

Now, try a similar exercise for the villanelle by returning to your end-word lists. Remember: The villanelle gains most of its power through the repetition of lines, but the lines also have to rhyme. So, when you put together your list of ending words, you have to find rhymes for the key words as well. Here's how such a list might look:

Villanelle Exercise

When you put your rhymes together for a villanelle, don't try to use fancy or unusual words. Surprise is good and necessary, but you will find it very difficult to sustain your rhymes in this form. Words used in ordinary speech will work best.

Now, work with the list you created for the villanelle. Here is an example of a completed exercise:

In the end, we live only by God's grace.

But when we pray we want the kind

that keeps the pimples from our face

.

that keeps our ball clubs in the race

for the pennant. Too late do we find

in the end, we live only by God's grace

.

Who cares if there is a place

where the check is always signed?

It won't keep the pimples from our face

.

Vain wishes are an empty space.

We need something else to remind

In the end, we live only by God's grace

.

Perhaps a shock of cold water to brace

us, a soapy cloth that won't blind,

that keeps the pimples from our face

.

The Greeks said our fate is a torn lace.

As we pass, keep this in mind:

In the end, we live only by God's grace,

the one who keeps the pimples from our face

.

Because of the heavy repetitions and rhymes, enjambment is difficult to manage in the villanelle. End-stopped lines tend to dominate, creating an even heavier tone. Again, it is important to find natural-sounding words for your rhymes. Practice will only improve your ability to make sense of the lines once you understand the form.

As another exercise, you might take what you have created in your villanelle and shape it into a terzanelle and a triolet. To create the terzanelle, you will have to revise the rhyme scheme completely, and for the triolet, you will have to cut eleven lines. Following are the first seven lines of a terzanelle:

In the end, we live only by God's grace

But when we pray we want the kind

that keeps the pimples from our face

.

As our vision darkens, too late do we find

that our hands can't grasp what we can't see.

But when we pray we want the kind

of grace that keeps our lunches free

.

Here is a complete triolet:

In the end, we live only by God's grace.

When our vision darkens, it's too hard to find

a soapy cloth to clear the pimples on our face.

In the end, we live only by God's grace.

Why care that our ball club's in the race?

Why care that the check is always signed?

In the end, we live only by God's grace.

When our vision darkens, it's too hard to find

.

Other Exercises

There are some other quick exercises you can try to generate the three main forms discussed in this chapter. For example, with the sestina, instead of repeating the same end word over and over, try using sound-alikes instead. If the word

feel

appears as an end word in your first stanza, try using

fell, fail, fall, fill

, and

full

as the repeating words in the following stanzas. With the pantoum and the villanelle, you can try repeating only the last words of the lines instead of the entire lines. The feel and the sound of both poems will be vastly different when you are finished.

One variation you can work with in all three forms is function or category shift. You saw an example of it with the sestina and you can review the complete discussion of this element in Chapter 5. The word

face

, for example, is used as a noun in the phrase “a pretty face,” as a verb in “she will face her accuser,” and as an adjective in “at face value.” These shifts can give you leeway in constructing your lines as well.

As you go through the exercises you have done, you might try to work with the other tools of the tradeâmeter, rhyme, and so onâto tighten up your lines. For example, you might revise your pantoum so that the end words rhyme. You might revise the sestina so that it follows an iambic pentameter. You could also work at the villanelle or its variations to regulate their meter. At all stages, you should experiment with the different forms and tools to see how they work together. And remember: You can never have too much practice!

Chapter 10

Writing about Love

L

ove, in all its forms, is perhaps the most common subject of poetry. The emotion is so intense that it begs to be expressed. If he is brave, a poet might express his feelings to the object of his affection. If not, he may simply record his hopes and longings in a journal and in poems. If his love interest does not return his feelings, writing poetry may operate as a coping mechanism. But if the person does return his love, his poems may be triumphant and joyful.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

While love will often bring you to the page to write about the joy or the suffering you are experiencing, you must remember that if you decide to shape those feelings into a poem for a reader, you have a responsibility to make the subject of your poem clear and engaging. Your reader needs to know the details of your situation so she can appreciate your poem. A chaotic gush of thoughts and feelings will not make sense to anyone but you. So, keep in mind what you read in Chapter 3, and use concrete details that appeal to the five senses.

Following Conventions

One convention of love poetry is that it describes in detail different aspects of the poet's beloved. If you choose to follow this convention, you can highlight a physical characteristic of your beloved or a character trait. For example, describe to your reader the long, soft hair, musical laugh, consistent generosity, or dimpled smile of the one you love. Use sensuous details to describe these traits. Do you remember how Shakespeare turned this convention inside out in his sonnet that begins “My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun”? You can take Shakespeare's approach and then reveal your true intent at the conclusion, or you can follow a more straightforward path. Whatever method you choose, don't forget the details!

Using Drama

You can also write about your beloved as if describing him to one of your readersâperhaps a close friend. Address this friend

as you

throughout the poem, and in a chatty tone, write out the description using words from the list that you already set down; then turn the description into a dialogue by having this friend respond. This form of writing will help you establish your own voice and force you to write with specific detail. If this is successful, your reader should see your love interest just as you do.